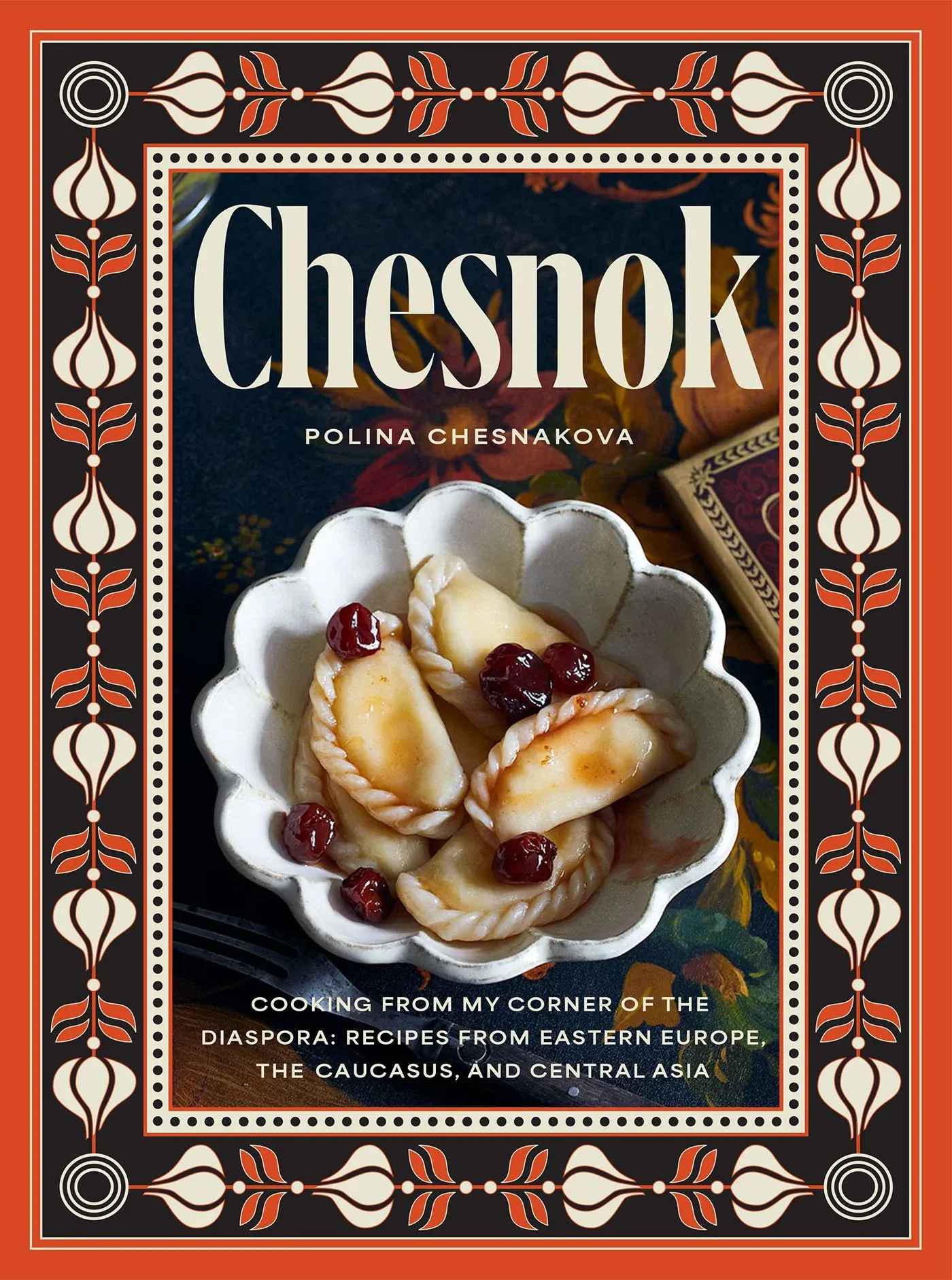

Polina Chesnakova's 'Chesnok'

An excerpt, two recipes, and a giveaway

Table of Contents

More and more, I get asked by friends to moderate their cookbook release events here in Boston, and I'm always happy to do so, but I haven't done that sort of thing often enough to not get nervous beforehand. I don't love public speaking, generally, and there's a lot riding on these events—it's a chance for the public to get to know the author's work, and I want to be sure I present it in the best light. I do a lot of agonizing about them as the day approaches, and I read and re-read the book over and over again, thinking up sparkling and intelligent questions to ask.

But after last week, with two such events in a span of just three days, I think I am getting the hang of this thing (a little). On Tuesday, I was at Brookline Booksmith, chatting with Polina Chesnakova about her new book Chesnok: Cooking From My Corner of the Diaspora: Recipes from Eastern Europe, The Caucasus, and Central Asia, then two days later I was at Sofra to discuss Rebecca Firkser's book Galette! I don't know if any of my questions were sparkling or intelligent, but both nights went pretty well, I think, and I feel like I've finally done enough such events to stress out a little less than before. (It helps that I've not been asked to moderate—or write back-cover blurbs—for people and books I did not already love, thankfully.)

Both books are really special, and I'm excited to share them with you here too. We'll get to Galette! soon, but today I want to feature Chesnok.

Chesnok is—after Hot Cheese and Everyday Cake—Polina Chesnakova's third book, and her most personal one. Polina was born in Ukraine to a Russian mother and an Armenian father, who met in Georgia. When her family emigrated to the U.S., they landed in Providence, Rhode Island, amidst a large community of refugees from throughout the former Soviet Union. The recipes and stories in Chesnok are drawn from Polina's experience growing up in the heart of a family and community of people joined together with a shared language (Russian), a shared history of displacement and cross-cultural connection, and a shared love of the foods from their collective homelands.

In the book's intro, Polina describes the challenges of summing up a culture that spans countless borders and ethnicities, particularly one defined in part by the current-day bad acts of their former masters:

Historically, the label "Russian" was used as a catch-all for the whole of the Soviet diaspora. Not just by those outside our community, but also within. When speaking with Americans, it's always been easiest to just leave it at "I'm Russian," because who has time to get into geopolitics?

Within the Soviet diaspora, we've always had an acute awareness of each other's ethnicities. "От куда вы?"—Where are you from?—is often the first question asked when meeting another Russian-speaker. It's the lens through which we see and place each other in our world. Historically, though, once that initial check was established, no one dwelled on who came from where, because we were brought together by larger forces at play: our shared language, history, and trauma. So, over time, we've allowed the label "Russian" to be used to lump us all together. We shopped at the local Russian store, visited the Russian neighborhoods in Brooklyn's Brighton Beach borough, and ate at Russian restaurants. If you looked a little closer, though, you'd see that "Russian" never really painted the full picture.

Five to ten years ago, I probably would've also called this food (and this book) Russian—with an asterisk. The explanation for the symbol buried somewhere in the intro. But Russia's recent war on Ukraine no longer provides us the luxury of that simplification. We have become too self-aware of our differences; our national identities taking precedence over our collective one.

Given recent events and the reckoning of self-identity that came with it, I use the term "post-Soviet" to describe this book and, more increasingly, myself. Some have argued that this term is problematic—that it perpetuates Russian imperialism towards former Soviet republics. Used in reference to Russia's neighbors striving to maintain their sovereignty today, this is true. But used in the context of a diaspora that wouldn't have existed if it wasn't for the Soviet Union and its collapse, it allows me to speak to the breadth of this specific group of people and their food-ways without having one culture or cuisine co-opt the others. Post-Soviet is the most accurate and concise descriptor I can provide, and the most transparent one.

Polina's own "post-Soviet" heritage encompasses Russia, Georgia, Armenia, Ukraine, and beyond, and the recipes in Chesnok reflect that. Her family straddles the culture of both Eastern Europe and the Caucasus, and her recipes embrace the flavors and approaches of both. There are hearty soups and stews, cultured dairy- and fermented vegetable-based dishes, and those containing earthy grains like buckwheat, millet, and cornmeal. And others where nightshades like tomatoes, eggplants, and peppers star, alongside an abundance of fresh herbs, nuts (especially walnuts), and sour fruits like plums, apricots, and pomegranates.

And there are loads and loads of sweet and savory dumplings and dumpling-adjacent dishes here: blinchiki (blini), syrniki (farmer's cheese pancakes), varenyky (Ukrainian dumplings, pictured on the cover image above), pelmeni (Siberian dumplings), khinkali (Georgian soup dumplings), treugolniki (beef turnovers) pirozhki (Slavic stuffed buns), vatrushki (farmer cheese-stuffed buns), and more. Given this, it would seem that at least one thing linking the diverse cultures of the post-Soviet world is a love for dumplings of one kind or another.

I love this book, and can't wait to have time to cook from it. I've got two (really three) recipes to share with you all today, both from Georgia, appropriately, since it is the hub of Polina's own post-Soviet journey. The first is imeruli khachapuri, a cheesy yeasted flatbread, a lesser-known but no less delicious cousin to the the canoe-shaped, open-faced adrjaruli khachapuri:

And then two versions of phkali, a vegetable- and walnut-based pâté that makes an excellent spread for some crusty bread:

I've also got a signed copy of Chesnok to give away to one U.S.-based Wordloaf paid subscriber. Just leave a comment below with your favorite post-Soviet/Eastern European/Caucasian dishes, and I'll pick the winner at random a week from today.

—Andrew

Excerpted with permission from Chesnok: Cooking From My Corner of the Diaspora: Recipes from Eastern Europe, The Caucasus, and Central Asia by: Polina Chesnakova, published by Hardie Grant North America, September 2025, RRP $35.00 Hardcover.

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.