Friday Bread Basket 6/24/22

Welcome to the Wordloaf Friday Bread Basket, a weekly roundup of links and items relating to bread, baking, and grain. This week’s email has a couple of stories about grain-based food traditions still in use today, with deep roots.

But first, I wanted to mention that next Tuesday, June 28, at 11am EST, I’ll be doing an Instagram live with my new pal Edna Cochez, on the kouign-amann recipe I developed for King Arthur earlier this year. I don’t have a link yet, but keep an eye out for one, or just tune in at the appointed hour.

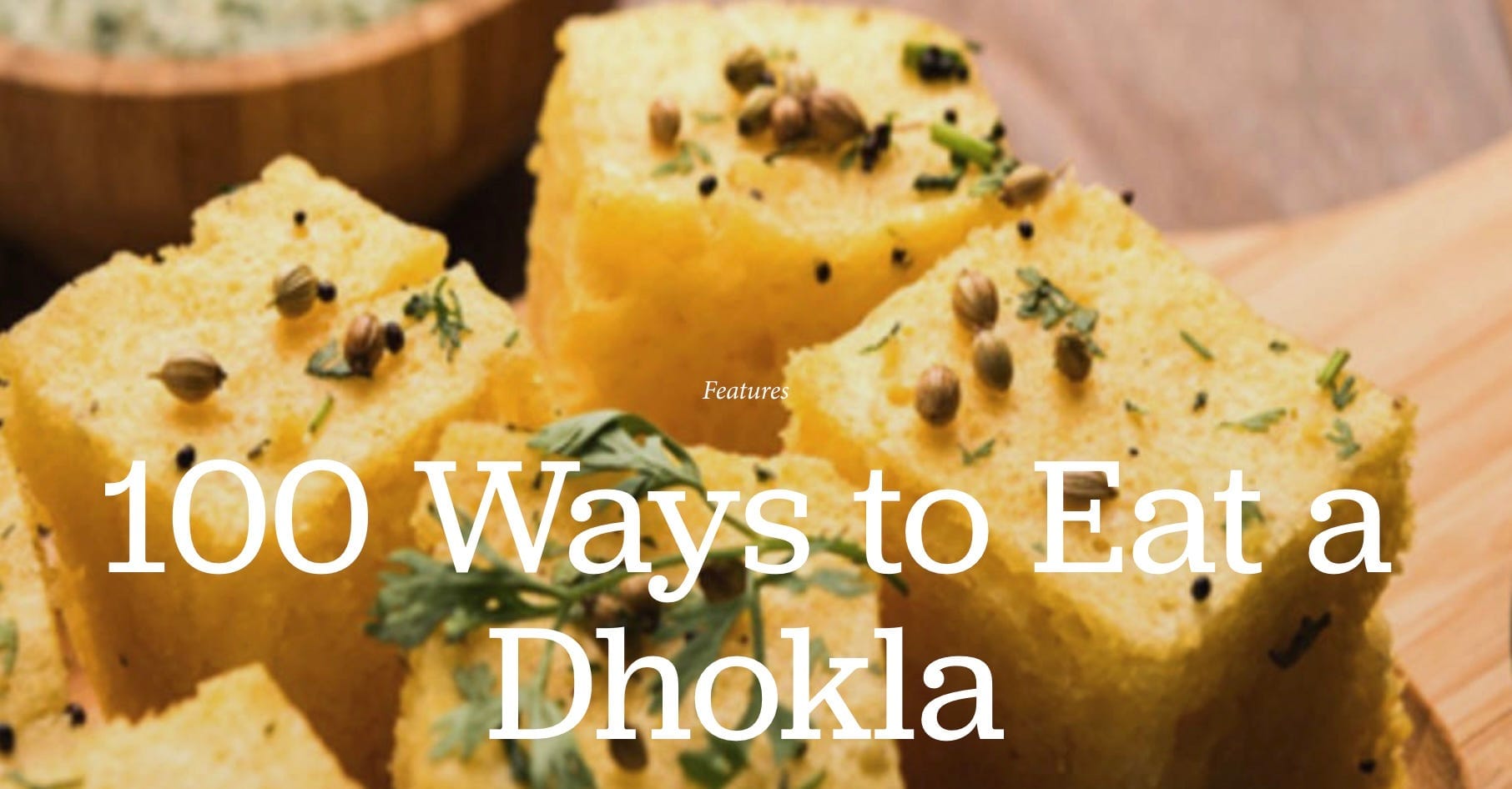

No wrong way to eat a dhokla

One of my all-the favorite Indian dishes is dhokla, a steamed, fermented-batter bread from Gujarat made from a variety of grains and pulses (or a combination of many), commonly topped with fried mustard seeds, coconut shreds, and coriander leaves. It’s a simple dish, but so very satisfying.

And, according to this wonderful Goya story by Chaitali Patel, an ancient one:

According to late food historian, KT Achaya, a similar dish called dukkai is first mentioned in 1068 AD, in Jain literature, and the term dhokla appears in the Varanaka Samuchaya in AD1520. In his book, A Historical Dictionary of Indian Food, he notes “A 2:1 mixture of rice flour and besan flour is fermented overnight with curd, and steamed in slabs, which are then cut into pieces and dressed with fresh coriander leaves, fried mustard seeds and shredded coconut.”

Part of Gujarati farsan, or dishes eaten along with the main meal, dhoklas have evolved with changing times and tastes. “Traditionally, dhoklas were made with a lot of grains, including makkai (corn) or bajra. Every part of Gujarat, almost every household, had their own version, using a different proportion of grains and lentils to make the flour. There are ones made with three dals, five dals, bhaaji (spinach), marcha (chilli), chora methi (split cow peas and fenugreek leaves), green peas, and one old recipe that uses pav,” says Sheetal.

I’ve never made dhokla from scratch, though it has long been on my list, and maybe someday I’ll have a recipe to share here. (But the instant box mixes sold at Indian markets actually make pretty great ones!)

Bread above all

I like the heat the tenderness the edible the lusciousness the song of a single person the bathtub full of water to bathe myself beneath the water

I like the wheat fields the plough the apricots those first flirts of the sun.

But bread above all.

—Arshile Gorky

Masa Art

I loved this Bon Appetit story by Andrea Aliseda—who will be guest posting for Wordloaf soon!—about the colorful, patterned tortillas that are popping up on restaurant menus and social media everywhere lately. Though novel-seeming, they are actually part of a long tradition of “ceremonial” tortilla-making in Mexico, used originally to convey secret messages across distances:

“There's two types of tortillas ceremoniales,” Hernandez says over Zoom. “There’s the one that we press and we ink. And then we have the ones with the colors.” During the Spanish conquest, which began in the 1500s, Indigenous people would hide a tricolor tortilla between stacks of single-color tortillas, and this marbled disk sent a message. “It was a meaningful tortilla,” Hernandez explains. It’s a technique that mixes three different kinds of colored maíz that can appear geometric or abstract and marbled depending on the technique.

This tortilla—unlike the plainly colored ones it was hidden among—acted as a way to maintain both identity and religion. These ceremonial tortillas were born in the Tlaxcala region. “It reminds you of how rich and beautiful the god de maíz is,” Hernandez says. “Because as you were being converted to Christianism, they were making you forget about your gods.” The stakes of keeping these traditions alive were high—Hernandez says the cost of being found out was death. The messages had to be kept secret, and the tricolored tortilla was a quiet form of resistance.

Detail from Old Mother Hubbard, illustrated by Alice and Martin Provensen, 1977.

That is it for this week’s bread basket. I hope you all have a peaceful weekend, see you next week.

—Andrew

Member discussion