Bath Time

On bassinage

Table of Contents

[N.B. I’m working on a future post on the joys and benefits of machine-mixing doughs, something I have covered here already, but it’s not ready yet. Today’s post really should come after that one, since it covers the use of a technique that works best (or only works well at all) when using a stand mixer. So as you read it, remember that this is as much about the virtues of machine-mixing as it is bassinage.]

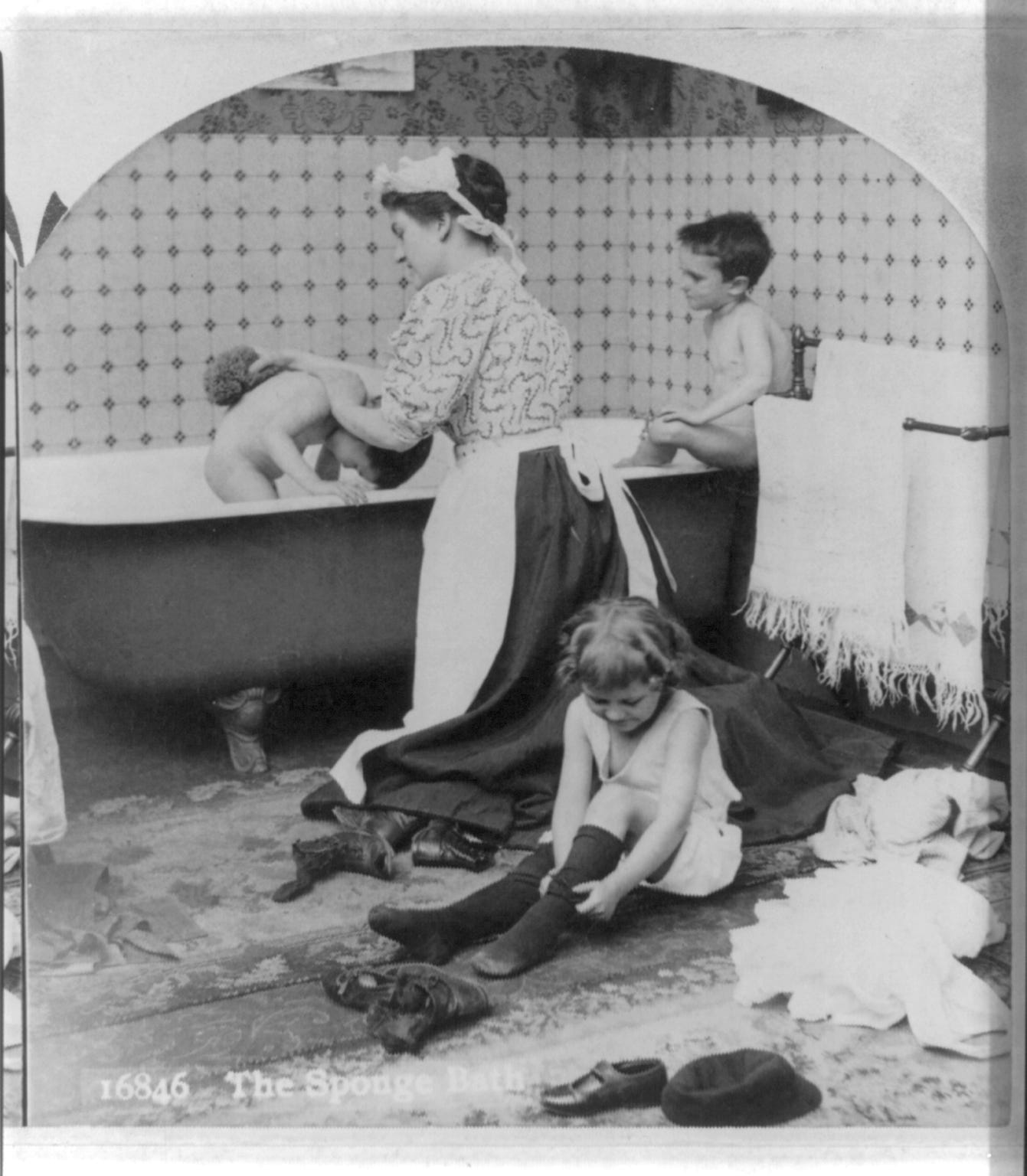

Bassinage, also known as double-hydration, is the deliberate holding back of a portion of the total water in a dough in order to promote quick and efficient development; once the dough is sufficiently strong, any remaining water is mixed in until it is fully incorporated. Bassiner means “to bathe” in French, and the use of the word bassinage evokes the second addition of water, at the start of which the dough will be soupy and wet, as if being given a bath.

Bassinage is most often used in high-hydration doughs that are otherwise too high in hydration to mix efficiently (or at all) when mixed in full from the get-go, but I’ve found that it can be equally useful even in doughs that aren’t excessively wet. And while there are some bakers who use it with hand-mixed doughs, it’s most commonly employed with machine-mixing, because getting the final water into the dough by hand—particularly when there is a lot of it—is challenging, and not necessarily fun.

If you were to add all of the water to a high-hydration dough at the very start of mixing, the gluten strands will be so dilute that they’ll slip past one another without linking up. Moreover, the dough will typically be too sloppy to catch on the dough hook, which will just spin around the bowl in vain. By holding back a portion of the liquid from the formula at the outset of mixing—say 5 to 20% of the total—you get a dough that is low enough in hydration to develop efficiently and quickly.

Every flour (or combination of flours) has an “ideal” range of hydration for mixing—something that gives a dough soft enough for the machine to handle without straining1, while dry enough for the mixer to do its work. A decent “moderate” hydration formula will sit within this range, and can be mixed easily with all of the water in the bowl from the start. But any formula with a final hydration well above it will likely benefit from the use of bassinage.

I’ve made plenty of high-hydration doughs entirely by hand, and I know it’s not essential to machine-mix them using bassinage. Periodic folding during the bulk fermentation and the dough-strengthening effects of fermentation itself (i.e, acidity) are often sufficient to yield a dough that is strong at time of shaping. But the differences between fully hand-mixed doughs and those developed in a machine using bassinage are obvious, and the resulting loaves are often much improved because of it—the doughs are often easier to handle at time of shaping, and the breads typically have a more-open crumb.

Bassinage also allows you to push the limits of hydration much farther than possible with hand-mixed doughs. For example, my standard refined (white) flour sourdough formulas typically start in the 70-75% hydration range. I’ve successfully pushed the hydration up to about 80% when hand-mixing, giving the dough a few extra folds during the bulk fermentation to build necessary structure. It works, but even then the dough is often quite sticky and challenging to shape, at least without skill and confidence.

But using bassinage, I’ve taken the hydration up to 85%, and I’m convinced I could go much higher if I wanted to. Doughs made with it, even those with loads of water in them, are supple and silky, and they hold themselves up in the tub from the start of the bulk fermentation. Unlike hand-mixed doughs, which typically need four to six folds during the bulk, a well-mixed, bassinaged dough only requires two or three, and they only serve to de-gas the dough and keep fermentation proceeding apace. By the second or third fold, the dough often has a permanent tautness and does not spread out much when given time to relax, even before the dough begins to acidify. (When folding hand-mixed doughs, I’ll typically fold every 30–45 minutes; with bassinaged doughs, I’ll do them once an hour or so. In both cases, I’ll stop when the dough ceases to spread appreciably between folds.)

[The two images on the left are of an 80% hydration, hand-mixed dough at the start of the bulk fermentation and the end. Those on the right are an 85%-hydrated dough, mixed in a machine, using bassinage. They are otherwise identical in weight and formulation.]

Bakers sometimes use the term “second water” to refer to the water added in the bassinage (and “first water” for the initial portion). It’s usually best to add the second water slowly, either streaming it in gently, or adding it a portion at a time, waiting for each glug to be incorporated into the dough before adding the next, to avoid splashing and sloshing, and to keep the mixer working efficiently throughout.

Bassinage is easy to do in a spiral mixer, but it can be done with planetary mixers and an Ankarsrum too; in fact, it can make these types of mixers more effective. Spiral mixers are much more efficient at getting wetter doughs to form than planetary mixers; bassinage is one way to make the most of the latter, where even a slightly over-hydrated dough can be challenging to mix.

When using bassinage with planetary mixers, it’s definitely a good idea to add the second water slowly, and to decrease the speed of the mixer during the addition, to prevent sloshing. Once the water is mostly incorporated, you can increase the mixer speed and continue mixing until the dough is even in texture. (A few bakers I’ve spoken to mix on speed two—4 or 6 on a KitchenAid—once the water is incorporated, suggesting it helps smooth out the dough more quickly and fully.)

As for the combination of hand-mixing and bassinage, yes, it can be done, but it only makes sense when you are hand-developing the dough. There’s no point in holding back any water when you are simply developing strength passively via fermentation and folding. If you actually knead your dough, you can certainly use bassinage to make the process easier by bringing the starting hydration down to a more-modest level; once the dough has the necessary strength, you can then add the final water by pinching and kneading it in, either all at once or in portions.

Finally, bassinage is an especially useful technique when attempting to push the hydration of doughs beyond what you are used to. Rather than adding all of the extra water from the start, you can instead mix the dough as normal, then add water a little at a time, testing the strength and the texture of the dough in order to decide when enough is enough.

For Breaducation, I am setting the hydration of most doughs to a somewhat conservative level, to make them approachable for bakers of all skill levels. Where appropriate, the recipe will clearly indicate the weight of +5% water, so bakers can inch up beyond that base hydration when they are feeling ready to.

What are your thoughts or questions about the bassinage technique? Hit me up in the comments below.

There’s not much you can do when a dough is by necessity low-hydration, as in a bagel dough. Every once in awhile I consider the idea of a “reverse-bassinage” for these doughs, where I’d hold back some of the flour in order to create a less-stiff dough for efficient mixing, then add the remainder at the end to bring it to a lower hydration. But flour doesn’t just slip into a dough as does water; it needs to be incorporated into the gluten network, which would require further mixing. The flour you add late would still need to be developed. I still may try it someday. ↩

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.