All Mixed Up (Part 1)

On dough mixing machines (and why KitchenAid hates home bread bakers)

Table of Contents

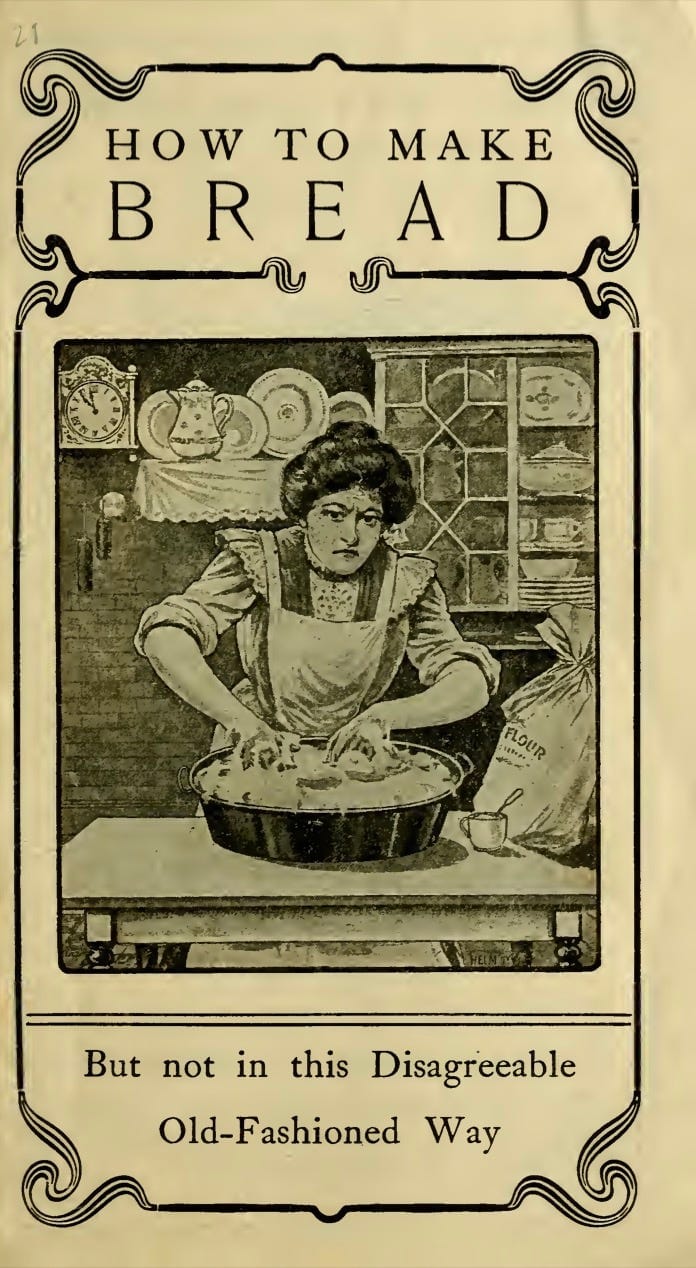

There are many people who mix or knead all of their breads by hand. While I fully respect this choice (while understanding that in many cases it is not a choice—some might not have have the room or money for a stand mixer, a large and expensive appliance), I don’t adhere to it myself. I make plenty of my breads by hand, and do think that getting your hands into doughs is one of the best ways to gain a kinetic and tactile understanding of how they behave. And I personally love the feel of dough in my hands (if not on them).

But I think there’s also no shame in using a machine to mix breads should you have one, and I think it’s strange when people turn up their noses on those who do. Machines are great! Like other tools, they are extensions of our hands, not replacements for them. They are essential when one’s own hands lack the strength, dexterity, or capacity to handle a particular task, and/or simply when we need to perform multiple tasks at once.

The idea that hand-kneading is a somehow more “authentic” approach to breadbaking is false. Yes, people made bread without the help of machines for thousands of years, but mechanical dough mixers have been around for more than a century now, so they are hardly some sort of fad. And it is a fact that most professional bread bakers, even those that employ "traditional” forms of baking like sourdough, use mechanical mixers regularly. That’s because they are efficient, allowing the baker to do more work in less time, and because they help protect the health of the baker working with large, heavy quantities of dough day-in, day-out.

There’s yet another way mixers are superior to hands for bread: They are more effective at mixing than the average set of hands. This is especially true when working with enriched breads, which often require late additions of sticky ingredients like butter. If you are one of those people who prefers to make brioche by hand, I tip my hat to you, but I have no desire to go this route. Not only is it messy, the body heat of one’s hands risks melting the butter before it is fully incorporated, a potential recipe for disaster. And while a mixer generates heat too, this is far outweighed by its efficiency.

(This sort of problem arises with lean breads too: Adding a loose levain or poolish to a stiff autolysed dough by hand takes time, effort, and likely a lot of hand-washing once complete. Ditto for a “bassinage,” where you add water to a dough at the end of kneading to adjust its hydration, something that might take even longer to complete by hand. A mechanical mixer, no matter what kind, can make relatively quick work of these sorts of tasks.)

It’s important to point out that mixing and kneading are not the same thing. Mixing is simply the combination of two or more ingredients into an even matrix; kneading is the development of gluten through mechanical action. Mixers can do both, obviously, but you don’t have to knead the dough to get good use out of one. I routinely use mine simply to quickly and efficiently get things combined, then I finish developing the gluten by hand (usually by folding during bulk fermentation).

Types of Bread Mixers

The two main classes of bread mixers are divided between “all-purpose” machines that do more than just mix doughs—whip cream or egg whites with a whisk, beat butter with a paddle, or even, with the use of larger attachments, grind meat or grains and roll pasta—and those that are dedicated to kneading bread dough.

Most so-called “stand” mixers are all-purpose machines, and most of the mixers sized and priced for home baking are stand mixers. The stand mixer was first dreamed up in 1908 by Herbert Johnston, an engineer for the Hobart Manufacturing Company, who saw a baker mixing bread dough by hand and decided there had to be a better way. Hobart produced the first commercial stand mixer, the 80-quart A-80, in 1914; Hobart mixers are still in use in commercial kitchens everywhere. In 1919, Hobart introduced the first KitchenAid mixer, a tabletop model sized for home use. The “K” model KitchenAid, with its familiar and patented silhouette, was introduced in 1937, and the basic design has remained the same ever since. (Attachments for the original model K can still be used on modern versions.)

Dedicated, one-purpose bread mixers—even those intended for home use—are heavier and larger than many stand mixers, in part owing to the power and heft of their motors. The first powered dedicated bread mixer was created by Joseph Lee, the same Black inventor who devised the breadcrumb making machine (and which Jeffrey Rubel wrote about here recently), who patented his device in 1894.

The other dividing line between mixer classes is in their mode of action: planetary or spiral. Most stand mixers are planetary mixers, while most dedicated bread mixers are spiral mixers.

Planetary mixers have the hook fixed to an offset shaft that rotates on its own axis while also rotating around the mixing bowl (just like planets move around the sun, hence the name); the bowl itself remains stationary.

Spiral mixers have an offset shaft that is fixed in place, with a spiral hook that rotates around its own axis; the bowl also rotates, pushing its contents toward the hook. Most spiral mixers also have a “breaker bar,” a metal rod that inserts into the bowl and stays fixed in place, which helps to prevent the dough from riding up the hook.

You can make excellent bread dough in a planetary mixer, but spiral mixers are generally considered superior to planetary mixers for bread, for a host of reasons. For starters, because of their design, they usually have more powerful motors than planetary mixers, which allows them to apply more force to the dough or to handle stiff doughs that might strain a planetary mixer. Spiral mixers are also generally more gentle than planetary ones; they place less stress on the dough while still working quickly and efficiently to develop gluten. (They also incorporate less air into the dough, which can help preserve the flavor of the wheat by minimizing oxidation.) Spiral mixers can often handle larger batches of dough, both thanks to their larger motors and larger, wider bowls.

All this comes at a cost, naturally. While no good mixer is inexpensive—the cheapest KitchenAid can be had for around $250, while better, larger models are more like $500—spiral mixers are far more pricey. The least expensive one around—the Famag Grilletta IM-5—costs $1400, making them an extravagance for the average home baker.

Why does KitchenAid hate home bread bakers?

Again, while you can mix great bread dough in a planetary mixer, if you—like nearly everyone else in the US with a stand mixer, myself included—own a KitchenAid, you probably shouldn’t, at least if you listen to KitchenAid itself. That’s because nowadays KitchenAid says you should mix bread doughs in its machines for no longer than 2 minutes at a time only on speed 2, and for a total mixing time of no more than 6 minutes.

The manual for my KitchenAid is light on any actual instruction, and the only reference it contains to bread making states: “Do not exceed speed 2 when preparing yeast doughs as this may cause damage to the Stand Mixer.” This KitchenAid web page contains a bit more intel on how the company expects you to mix bread in one:

Mix bread dough for no more than 2 minutes and then, depending on the recipe, knead for 2–4 minutes.

and:

We recommend only mixing bread dough on speed 2. At a lower speed, the mixer won’t deliver enough momentum to effectively knead the dough.

I haven’t yet tracked down older versions of the KitchenAid stand mixer manuals (if you have one, let me know, I’d love to compare it to newer ones), but I’m positive this is not what they used to say. Worse, nor does it line up with nearly every machine-mixed bread recipe in the known universe: Most machine-made bread recipes require at least 6 minutes of mixing time, and many go well beyond that. Many of them also call for mixing speeds higher than speed 2, which is one notch above the lowest, out of a total of 6 possible speeds. Additionally, many doughs—like bagel or pizza doughs—are so stiff that the hook will struggle or even not move at all on speed 2, which means you are out of luck if you are a rule-follower and happen to want to make bagels or pizza.

Oh, and in case you were wondering if this caution only applies to smaller or less powerful KitchenAid machines, the answer is: Nope! KitchenAid makes at least 5 distinct models of stand mixers, from 3.5 to 8 quarts in capacity and 250 to 575 watts in power, and the “2-minute/speed 2” rule applies across the board. You can spend $850 for an 8-quart, 1.3 horsepower “Commercial” KitchenAid mixer, but you still aren’t supposed to mix for longer than 2 minutes at a time on speed 2 (despite the spec sheet saying this model “easily handles recipes requiring longer mixing, kneading and whipping times”).

Why would a machine that was first invented for the purpose of kneading bread more efficiently no longer really be usable for bread, at least if you follow the manufacturer’s guidelines? And, more importantly, should you follow those guidelines (and basically give up making bread in one)?

The answer is I don’t know. All I can say for sure is that something has changed at KitchenAid, but whether or not it is the machines themselves, or simply that the company has decided to adopt a cover-your-ass attitude to bread baking to avoid lawsuits from disgruntled owners whose machines break down under what every single one of them would reasonably consider “normal” use for an appliance of its price and reputation, I have no idea.

I personally think it sucks that a respected company that has cornered the American stand mixer market for more than 100 years has decided they don’t care about bread bakers any longer, and I wish this fact were more widely known. For the time being, my recommendation is that if you are in the market for a new stand mixer and plan to bake bread, avoid buying a KitchenAid entirely. There are other options, though unfortunately they are more expensive, at least when you set them next to KitchenAid’s lower-end models. But once you start comparing higher-end models, the price difference starts to fade. The KitchenAid 600 has a list price of $550, and the larger and more-powerful 700 and 800 models are $100 and $200 more expensive, respectively. Meanwhile, the Ankarsrum, with a 750-watt motor more powerful and a bowl capacity larger than any of these, is $750. (I’ll talk about the Ankarsrum in part 2 of this post, next week. In the meantime, there’s always the story I wrote about mine for Epicurious.)

And what should you do if you already have a KitchenAid mixer?

With the caveat that if yours breaks it ain’t my fault, I think you should consider using it the same way you always have, though maybe a bit more conservatively, in order to keep it running as long as possible. Here’s what I recommend (and what I now do myself):

- Run it on speed 2 whenever a recipe calls for mixing on “low” speed.

- If the hook strains to mix on speed 2, increase the speed to 4.

- Run it on speed 4 whenever a recipe calls for mixing on “medium” speed (it’s hard to find a recipe that mixes at higher speed than medium, and 4 is plenty fast enough for most doughs).

- Try not to run the machine longer than 10 minutes at a time. (Yes, I know that this is almost double the maximum time than KitchenAid recommends, but I’ve found numerous instances where anything less than 10 minutes wasn’t enough.)

- Keep an eye on the temperature of the motor when in use. It’s fine if the top of the mixer is warm to the touch, but if it gets so hot that you can’t hold your hand there for more than a second or two, stop the machine and let it cool down before proceeding.

- Similarly, use rest times during mixing to keep the motor from getting too hot. If the recipe calls for a total of 10 to 12 minutes, for example, try instead mixing for 6 minutes, resting for 5 minutes, then mixing for an additional 4 to 6 minutes. The short extra rest shouldn’t affect the fermentation noticeably.

- Look for recipes that use an autolyse to develop gluten passively, which will help shorten the overall mixing time. (Mine almost always include an autolyse.)

Beyond that, I think you probably should familiarize yourself with what options you have if and when your machine breaks down. While it is a messy and slightly technical job requiring a few unusual tools, fixing most busted KitchenAid mixers is actually pretty straightforward. That’s because some time ago KitchenAid replaced a metal “worm” gear in their motors with a plastic one that is designed to disintegrate if the machine is overheated or overtaxed. It’s sort of a failsafe feature, meant to protect the motor from busting permanently. (Which I suppose could be considered a good thing, though I’d much rather they’d improved the design of their motors to not bust when used the way they are meant to be.)

The part is easy to find online, but make sure you get the correct one for your particular machine. And anecdotally I’ve heard it is best to avoid 3rd-party knockoff versions (look instead for “genuine OEM” parts). There are numerous guides to the procedure available online, especially on YouTube.

And if you don’t want to get grease on your hands, you might want to look around for an appliance repair shop near you that services KitchenAid, to avoid having to ship the machine to Ohio to have it done.

I bought my KitchenAid for the purposes of testing for my book, since I figured that’s what most of my readers might have access to and because it has a glass bowl which makes it easy to photograph what’s happening inside the machine. But I recently realized that it would also serve as a good test case for KitchenAid’s new bread mixing “rules.” I am putting this machine through its paces right now, using it on a near-daily basis, and I am not following KitchenAid’s advice. If it survives the next 14 months of testing, then maybe these rules are overblown. If it busts, I’ll have a chance to take it apart and (hopefully) fix it. Either way, it’ll be useful intel for when I write the stand mixer chapter for the book.

Stay tuned for part 2 of this post next week, when I’ll cover alternatives to the KitchenAid for the serious home bread baker.

—Andrew

References & Further Reading

Forbes: How This Unsung Black Entrepreneur Changed The Food Industry Forever—And Made A Lot Of Dough

National Museum of American History: "Universal" Bread Maker No. 4

Martha Stewart: A Brief History of the Stand Mixer

Smithsonian Magazine: For 100 Years, KitchenAid Has Been the Stand-Up Brand of Stand Mixers

Archive.org: How to make bread : but not in this disagreeable old-fashioned way

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.