On Being Blue

On cyanotypes, tannins, and bread

Table of Contents

Cyanotype was discovered by Sir John Herschel in 1842, making it one of the earliest-invented photographic processes. The photosensitive emulsion in cyanotype—i.e., the chemicals that respond to light to yield an image—is iron-based, and it normally produces a sky blue or aquamarine image. (Until very recently, cyanotype was also the process used to reproduce architectural drawings, hence the reason they are known as “blueprints”.)

But the finished cyanotype can be treated with variety of different liquids to shift the color of the image in one direction or another, in a process known as “toning.” Common choices for toning baths are things like green or black tea, coffee, or wine, all of which contain tannins.

Tannins are a wide class of compounds produced by plants, including many of our favorite foods. We know tannins best because they are the source of the dry, astringent sensation produced in the mouth by red wine, tea, and chocolate. In cyanotypes, the tannins in the toning bath chemically bond with the iron in the print to form colored pigments like the ones in the image above.

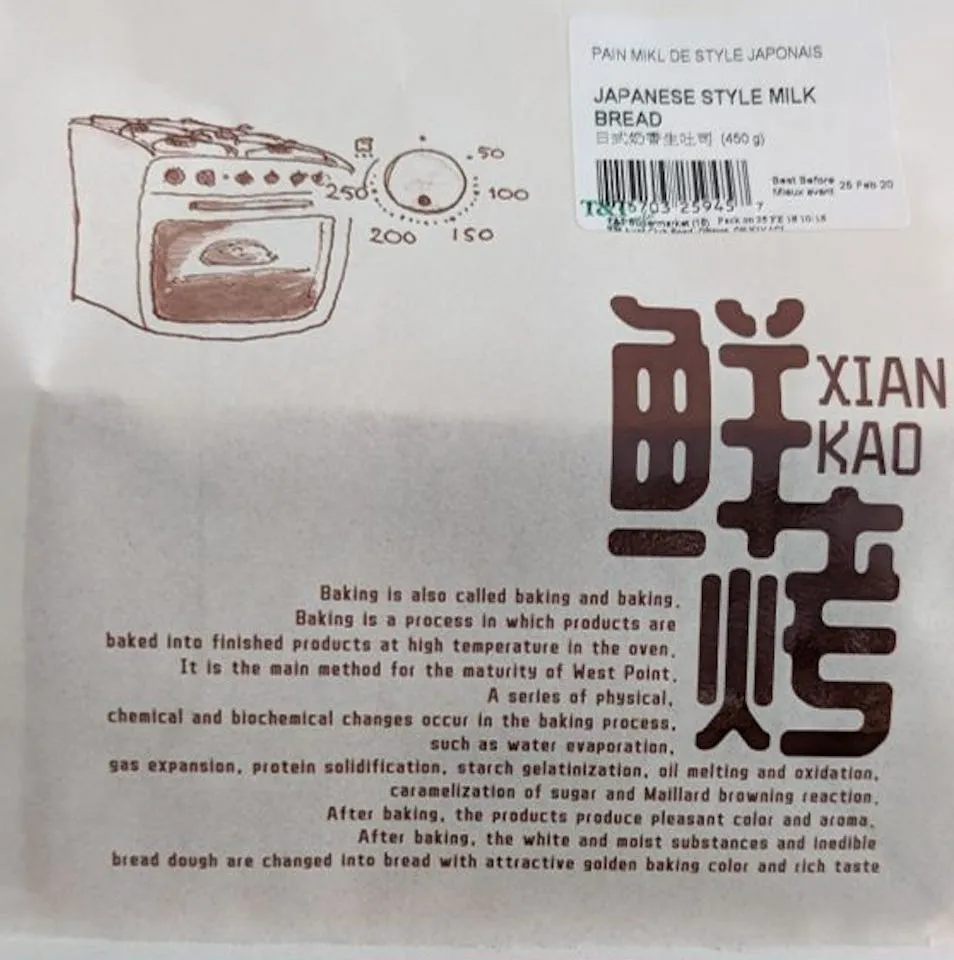

It turns out that tannins can be used to “tone” breads too. For years, I noticed that when I added walnuts to my breads, the dough would occasionally turn a crimson color, particularly where it came into contact with the nuts. But the effect was inconsistent. Sometimes it would be dramatic, while at other times it wasn’t visible at all.

The purple color was beautiful and I wanted to be able produce it more consistently. After some sleuthing, I finally sorted out the chemistry behind the effect: the reaction between gallic acid—a breakdown product of the tannins found in the walnuts’ skins—and iron to form a purple pigment. The reason the effect appeared inconsistently was due to the fact that some flours naturally contain more iron than others; without it, the tannins remain nearly colorless.

So I thought, why not just add iron to the dough, to guarantee the purple color would appear? I tested my idea by soaking some walnuts in water for a few hours to leech out the tannins:

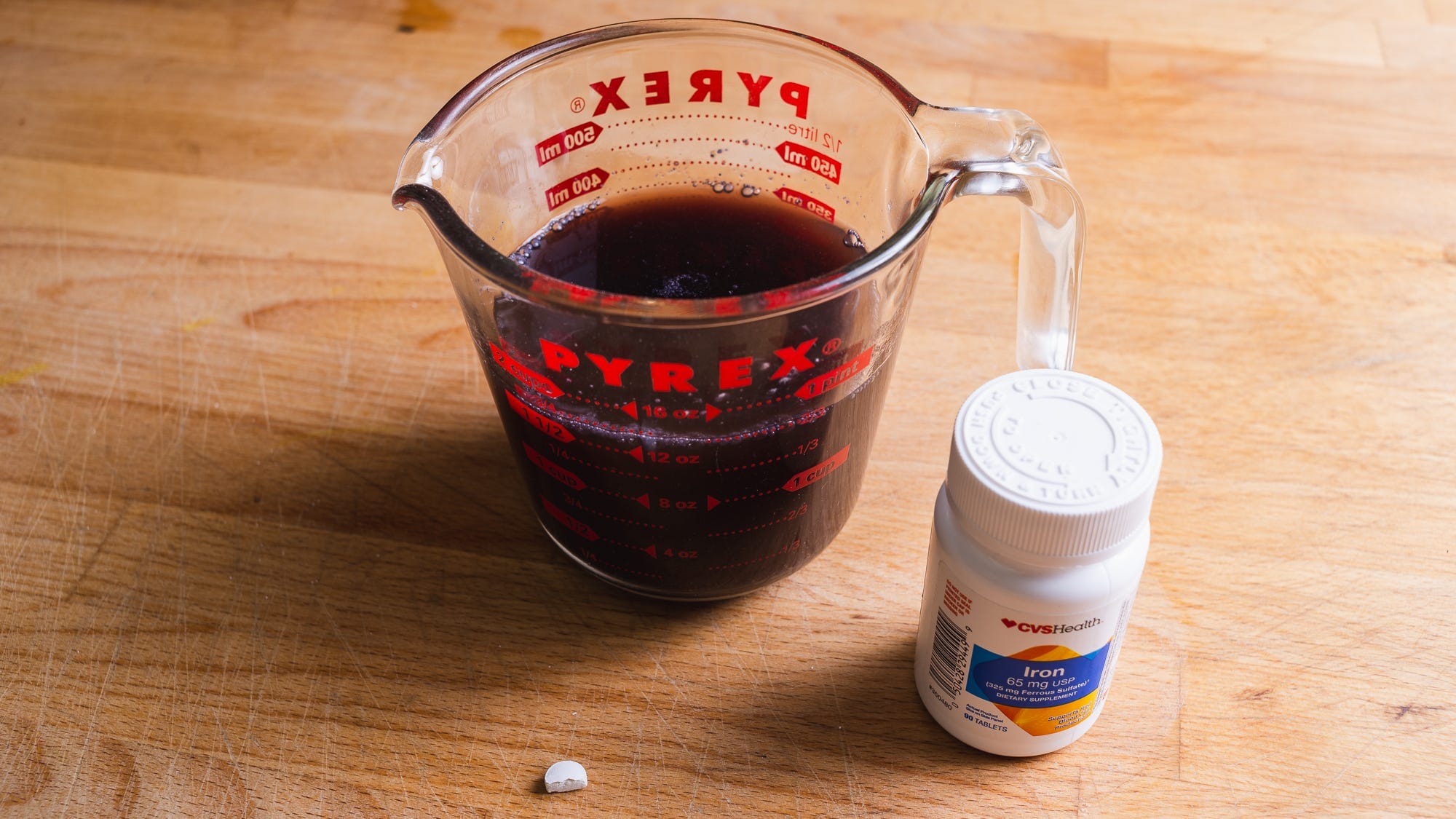

And then stirred into it a small portion of a crushed up iron (ferrous sulfate) supplement tablet:

Bingo†. (Soaking the walnuts ahead of time allows one to evenly distribute the purple color throughout the dough, instead of having it localized mainly around the nuts.)

Should you want to dye your breads purple too, I’ve shared my method in detail here: Walnut Pain au Levain.

UPDATE (12/19/20): While I was writing this post, it occurred to me that this trick should work no matter what the source of the tannins, just as it does with cyanotype. But I’d never tried it on any other tannins until today, when I tested the reaction of iron with green tea:

Unsurprisingly, green tea is even more tannic than walnuts, and it took far less iron here to produce the color change.

†As it so happens, this is the exact same chemical reaction used to make iron gall ink, the standard choice for writing and drawing inks in Europe from the 12th to 19th centuries. Iron gall ink was made by combining ferrous sulfate with an extract of oak galls, leading us all the way back to that cyanotype I posted above.

—Andrew

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.