Rethinking Autolyse

Giving it a rest

Table of Contents

In the introduction to Breaducation, I mention that the "education" in the title is first and foremost mine. Making it, I taught myself to bake and to think like a baker. I do hope that the book will be a useful resource for others, but if nothing else, writing it has given me the gift of an opportunity to question everything I do and make considered choices about how and why I do things. I'm sure my baking will continue to evolve, but at least now "my" approach is codified and I can just make things.

A lot has changed about my way of doing things since I began working on it, in many cases radically so. While I've added numerous methods to my repertoire—either gleaned from others or invented by me to address a problem seemingly no one else had solved—in most cases it has gotten simpler. I'm admittedly still a "fussy" baker compared to many others, but I these days if I use more-involved or complicated approaches, it's because it makes for better breads or improves one's chances of success getting them.

I tested some of the recipes in the book many, many times, so I had ample opportunity to compare the results I got when I did things one way vs. another. I was often in a rush to get the work done as quickly and efficiently as possible, so anything that added time to the process was especially open to question. But I tried to consider everything I do, eliminating any method or ingredient that had no experiential justification, whether or not they were time-consuming or fussy.

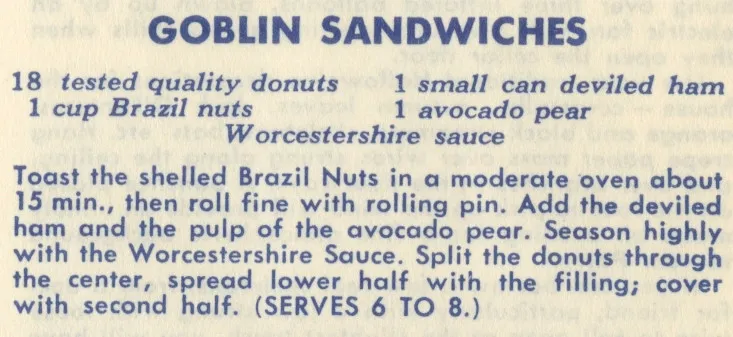

There are many examples of methods or ingredients I've jettisoned, but perhaps the most glaring one is the use of autolyse, the resting of a dough in the absence of salt, yeast, or leaven prior to the final mix. Autolyse was invented in the 1970s by Raymond Calvel, a French baker and bread scientist, who was in search of means to protect the flavor and appearance of breads by eliminating the need for long, intensive mixing, which can oxidize flavorful carotenoid pigments in the flour. Here's how it is explained in the English edition of his book, The Taste of Bread:

During experiments in 1974, Professor Calvel discovered that the rest period improves the links between starch, gluten, and water, and notably improves the extensibility of the dough. As a result, when mixing is restarted, the dough forms a mass and reaches a smooth state more quickly. Autolysis reduces the total mixing time (and therefore the dough's oxidation) by approximately 15%, facilitates the molding of unbaked loaves, and produces bread with more volume, better cell structure, and a more supple crumb. Although the use of autolysis is advantageous in the production of most types of bread, including regular French bread, white pan sandwich bread, and sweet yeast doughs, it is especially valuable in the production of natural levain leavened breads.

—The Taste of Bread, by Raymond Calvel, Ronald Wirtz, and James MacGuire, p. 31

The common wisdom about autolyse is that the rest period makes doughs more elastic (stronger) prior to mixing, which allows it to be developed in less time once mixing commences. But that's not what Calvel says above. He does claim it reduces mixing time, but he doesn't mention elasticity at all. Instead, he says it increases extensibility, the ability for a dough to elongate easily. A certain amount of extensibility in a dough is necessary, and a soft dough might "reach a smooth state" more quickly during mixing, but it doesn't follow that an autolyse step also results in increased elasticity.

Ian Lowe is skeptical about the virtues of autolyse too:

The term and method we know today as “autolysis” or as an “autolyse step” was created by Raymond Calvel, a French bakery teacher. After a bad harvest, France had to import strong, hard North American wheat, which Calvel (and I) believed inappropriate for French bread applications. The flour made for a tight, tough product with diminished volume. His goal, as a researcher, was to find a way to weaken the flour so as to attain a soft dough.

His solution was “autolysis,” allowing a barely-mixed combination of only flour and water to sit at ambient temperature for a specified period of time. (He tested durations up to 24 hours.) He chose the term “autolysis” because he believed the processing step degraded a significant amount of gluten. (It does not.)

Why did he believe this? Because he observed a weakening effect, resulting in, according to him, increased dough extensibility. (It does not.) For the rest of his life he became a vocal proponent of autolysis. Nowhere did he claim it increases gluten development. (It does not.)

There is no question that an autolyse does something; even a 10- to 20-minute rest will transform a rough, shaggy mass into a smooth, extensible dough. So it's easy to see why bakers might latch onto the idea that it ultimately increases dough strength. But the same transformation occurs when a dough is rested with salt and levain in it too—anyone who's done folding during bulk fermentation knows that doughs tend to smooth out and become softer between folds.

Ian has an alternative explanation for the increased softness of a dough observed after an autolyse:

Autolysis, rather than “destroying gluten,” prevents the unfolding, hydration and physical stabilisation of some portion of the largest-sized glutenins by a good solvent, thereby decreasing the total amount of these glutenins able to participate in gel-network formation. This is experimentally confirmed by research into passive hydration of “zero-developed” doughs quantifying the amount of “glutenin macropolymer” present in such dough systems at different time points and under different mixing regimes.

The reasons for this effect are somewhat technical (he explains it in full in the post), but the basic idea is this:

Gluten-forming proteins must first hydrate before they can link together. But they are hydrophobic, meaning they don't particularly like to combine with water. They are more than happy to combine with one another, however. Proteins are chains of amino acids; in order to take up as little space as possible within the grain, the chains naturally fold into compact spheres, with much of their bonding capability locked away on the inside. Just like you cannot make a sweater from a ball of yarn without first unwinding it, individual gluten-forming proteins must unfold before they are able to link together. Mechanical mixing overcomes both of these tendencies: it forces water into the proteins, softening them so they can unfold, and it stretches them out, making them more able to bond with one another and form stable networks.

If, however, flour and water are combined and mixing is delayed, some portion of the gluten-forming proteins will cluster together, making them inaccessible to water and unable to participate in network formation at all. As a result, the dough will reach peak strength more quickly during mixing, but the maximum amount of strength in the dough will be lower than it would be if it had been mixed immediately. Thus, the 15% reduction in mixing time is a result of a comparably reduced amount of gluten that is available to form networks.

I don't know for certain that Ian is correct here, but his explanation has the ring of truth to it, and he claims it is based on empirical data. What I do know is that I've eliminated autolyse from most of my breads and I haven't noticed any downsides; my doughs get plenty strong during the mix, and do not take noticeably longer to do so. Most artisan bakers—me included—employ much shorter mixing times than bakers did during Calvels' day, so flour oxidation is not really a concern. And the theoretical savings in mixing time are hard to justify when the autolyse itself takes far longer than the few minutes or so it might shave off the mix.

The upsides, however, are obvious: The doughs get mixed and into the bulk proof in minutes, and it is far easier to control their temperature at the end of mixing, because the dough is mixed as soon as the flour and water are combined. (In order to combine desired dough temperature calculations and autolyse you need to anticipate the drop in temperature that will occur during the autolyse and use warmer water to compensate, and even then it is something of a guessing game.) Are they better because I've stopped autolyse them? I think so, but it's hard to say for sure. They are definitely better than ever, though I cannot pinpoint one single reason for that, since I've refined so many elements of the process.

So, nowadays autoylse is out, except in one instance: where the dough contains entirely or mostly whole-wheat flour. Wheat bran is extremely slow to hydrate compared to starch and proteins; with whole-wheat formulas, I still let the flour and water sit for an hour or so, so that when it comes time to mix, the bran is as soft as it can be. But even in these cases I'm not entirely sure it's necessary, and I have more testing to do before the book is in the can.

[UPDATE, one hour after I sent this out.] Welp. I just mixed up two whole-wheat doughs (the only two 100% whole-wheat formulas in the book) without an autolyse and both mixed up very nicely, so it looks like I'm ditching it entirely.]

[UPDATE two.] I should have made this more clear when I added the above edit. There are a couple of 100% whole-wheat formulas in the book, but both of them use a "sift-and-scald" approach, where I sift off the bran, cover it with boiling water, and let it sit awhile; I then mix the dough to full development, and then add the bran scald at the end. This solves the same problem that an autolyse would, but is more effective. I've rarely made a 100% whole-wheat loaf I've loved without a bran scald, which is why it's my go-to approach for these sorts of loaves. So, while it is true that I don't use autolyse anymore, you might still want to use it if you are making them the "traditional" way.

So should you autolyse your doughs? Maybe, maybe not. If it works for you and you don't mind the extra time it adds, then stick with it. But if you've done it without questioning whether it is necessary, give the practice a rest and see if you notice a difference.

Would love to hear others thoughts on all this, particularly if you've given it up yourself.

—Andrew

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.