Book excerpt: "Wheat", From Kate Lebo's 'The Book of Difficult Fruit'

And a recipe for whole wheat pie dough

Table of Contents

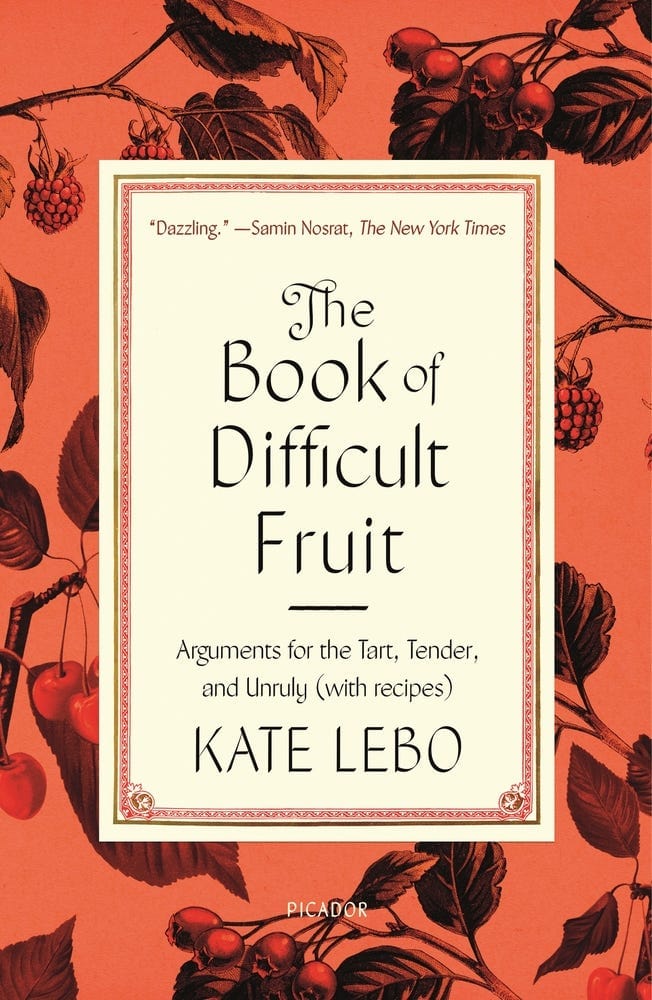

As I mentioned last week, September is a month of abundance and fruit. And also of guest contributions to Wordloaf, as it turns out. This week, I have an exclusive excerpt from one of my favorite reads of 2021, Kate Lebo’s The Book of Difficult Fruit.

The Book of Difficult Fruit is many things at once and hard to sum up in a way that does justice to its joys and wonders. It is an abecedarium1 and a love letter to some of the world’s most ornery and prickly fruit, eschewing apples in favor of aronia (or chokeberries) and blackberries before bananas. It’s a memoir in the form of a prose-poem, threaded through by a family mystery that only comes into relief as the book progresses. And it is a collection of recipes, some concrete and others more whimsical, all of them practical—there’s one for Elderberry Syrup and another for Hiker’s Toilet Paper (made from thimbleberry leaves). In short, it is a gem of a book you are going to want to read and re-read.

Kate is a subscriber to Wordloaf(!), and she’s graciously shared with us all a slightly-abridged version of her chapter on wheat—including her wise recipe for Whole Wheat Pie Dough—which I think will do a better job than I ever could in enticing you to seek out a copy of this book for yourself. I hope you will love it as much as I do.

—Andrew

W: Wheat

Triticum aestivum

Poaceae (grass) family

From the ages of twenty-seven to thirty-two, I paid my rent by cutting all-purpose wheat flour with Irish butter to make pie pastry. It was an emergency-fund / self-help scheme. If I turned one kind of dough into another by the first of the month, could I spend that month at home as I wanted to spend it, working for myself—writing? Compared with the other pursuits of my life, baking pies was easy; the failure, if I failed, simple to identify and redeem. This is when the kitchen became an extension of my writing studio, where I first transformed raw fruit and pastry into something that required no explanation or argument, something almost everyone knew how to receive. I needed that then, and I need it now. Not just to have made something immediately delightful, but to be the sort of person who knows how to make something immediately delightful. Something sweet and good, then gone.

Wheat is a relatively quick cash crop with a huge market, which is as true now as it was when Civil War veterans and European immigrants rushed into Minnesota and the Dakota Territory to stake claims, raise wheat, and sell it to the mills clustered around Saint Anthony Falls. In 1850, Minneapolis milled fourteen hundred bushels of wheat. By 1870, 18.9 million bushels poured through its mill district.

Refined, bleached flour made lighter pastries and finer breads than the whole-grain stuff, which was rough, dark, and assertively wheaty, and went rancid fast. University researchers sponsored by Washburn- Crosby (progenitor of General Mills) and its competitor, Pillsbury, pitched this new product to the public by saying that bleached and bromated flour was tastier, healthier, pure.

A decade into the twenty-first century, when W and I were still in love, we discovered that if one half of a relationship is a baker and the other is a celiac, the baker must take surgical steps to contain her gluten. The celiac, for his part, must regard the baker’s wheat as poison.

There are three basic parts to wheat. Technically, gluten isn’t one of them. The germ, where the seed is stored, is full of nutritious oil and goes bad fast. The bran, full of fiber that protects the seed, also goes bad fast, and is sharp in a molecular way I don’t really understand, except by effect: it cuts gluten bonds as they develop, making a crumbly dough. The endosperm are what’s prized in white flour. Mostly starch composed of glutenin proteins and carbohydrates, these are the substances that—when developed with moisture and pressure—become the gluten bonds that give piecrust structure and flake, make the glue of wheat paste, and sicken celiacs.

I remain uneasy with the terminology of W’s illness. Once he was diagnosed, in the last year of our relationship, “celiac,” an appositive for “a person with celiac disease,” sifted over other identifying nouns. Like how we describe people according to where they are from, or what they do. Salesman, Seattleite, Celiac.

I had a separate drawer for utensils that touched wheat, separate jars of peanut butter because I still liked to spread mine on wheat bread. W thought that if I had recently eaten wheat my kiss would make him sick. I conceded to this argument, because to do otherwise would boil down to a command, a manipulation, a plea: Kiss me. Please, kiss me.

In 1921, the marketing department of Washburn-Crosby introduced Betty Crocker, a personification of home economists and domestic scientists. Women who, rather than riot for the vote, empowered themselves by remodeling the feminine sphere with the masculine language of science. Betty had all the answers to a certain kind of question: why your bread didn’t rise, why your cakes burned, why your pie dough tasted like dust. Over her first century, she aged from fiftyish to fortyish, down to thirty-five, and back up to fortyish, and was presented as a brown-haired, blue-eyed Caucasian woman except for a period in the 1990s when she looked vaguely mixed-race. She was ever new, ever improved until the beginning of the twenty-first century, when depictions of Betty largely dropped off General Mills packaging, leaving her physically erased but still present as a brand and a logo, a food goddess with no body to feed, her white name suspended in the curve of a red spoon.

My version of our story is simple. It’s W’s fault, even though he is sick. We cannot help how we are sick, but we can help how we live with being sick. Wheat made him sick. Every day was a series of things he could not do because he was sick, like leave the house, and things he did anyway, like drink.

Flour especially made him sick, or the idea of it. If I was making pie, he would run out of the room wailing, “You’re trying to kill me!” as a joke, but then I’d find him moaning in bed, clutching the parts of him that hurt. “My guts hate me,” he said. “There’s flour in the air,” he said. “Are you trying to kill me?”

Later, after a friend asked, “Well, were you?” I thought I’d see how it felt to say yes.

It was not him, exactly, I wanted to kill, but the way his body turned the food I made him into poison. That is what I wanted to kill.

That, and the part of him I thought took pleasure in surrendering to sickness, like it was a shelter that kept him safe.

He couldn’t be touched, but he would allow me to lean into him. I’m bloated, he said. My stomach hurts. He couldn’t be kissed. Your breath smells like coffee, he said. Coffee made him sick, too.

I used to wake up angry, aching for sex. I used to sleep late, trying to sneak by my rage. I used to drink with him. Vodka made us feel close.

You can’t say these things out loud to a sick person. It’s not fair.

From the Song of Solomon: Your body is a heap of wheat encircled with lilies.

From The White Ladies of Worcester: If roses overgrew the wheat, we should dub them weeds, and root them out.

“I never asked you to help me,” he said when I left.

Wheat dust, a by-product of the flour-milling process, is more explosive than gunpowder.

On the day it blew up, Washburn A Mill was the largest mill in the United States, producing one-third of all of Minneapolis’s flour output and employing over two hundred people. A jury investigation by the coroner of Hennepin County into the events of May 2, 1878, found no evidence that “the mill was being run in an unusual manner in any respect” and determined that “it is not possible to fix upon anyone blame for special neglect or carelessness on that occasion.” They accused air purifiers—which seemed to have done the opposite of what their name implies—of causing “a needless amount of flour-dust to settle throughout the mills, stored ready for an explosion.”

It was no one’s fault, then, that an hour after the night shift started, two unfed milling stones shot a spark into a pile of middlings, where it smoldered. It was no one’s fault that an unlucky draft of flour- soaked air happened across the blaze and exploded, which threw up dust nearby, which exploded, igniting a chain reaction of fire and flesh and stone and wheat that did not stop until it had consumed the entire building and three neighboring mills, killing eighteen men, including the entire night shift of the Washburn A.

It is true that the idea of wheat became a poison that W and I both handled. It is true that, at any given time, I kept ten pounds of wheat flour in our house. It is true that sometimes, especially at the beginning, the immediate after of his diagnosis, I would forget he couldn’t eat wheat and find some incidental way to add it to our meal: gluten-free fish tacos battered with beer, cornbread made with contaminated cornmeal. It is true that sometimes I’d get so frustrated by the job of adapting gluten-full recipes that I’d sink to the floor and weep. It is true that it took me time to accept that we had to worry about contaminated corn, that a sack of yellow meal, sunny and humble and supposedly our alternative, would also poison him if it didn’t have the magic symbol on the back: a stalk of wheat jailed in a crossed-out circle. It is true that he was the axis our meals turned around.

Also true: I turned the wheel of our meals. I liked the way my hands looked, steady and capable at the controls, secure in the fiction that he couldn’t pilot this route himself. Did he cook for himself when I met him? Did he cook when we were together? All I can remember are his gluten-free waffles, torn from the bag and toasted before work.

It would be easy but wrong to call wheat simply poison, simply a contagion of no nutritional value. Like we’re members of the gluten-free church, those people who preach, “There’s hardly an organ that is not affected by wheat in some potentially damaging way” (William Davis, Wheat Belly), and sell their diagnoses by promising, “Elimination of this food . . . will make you sleeker, smarter, faster, and happier.” Purity of this kind is impossible. It is an idea, not a cure.

Can we also say that part of the weight of being ill is protecting the people you love from your suffering? Within relationships, there would be sickness in containing your suffering too well, and sickness in not containing it at all.

Can we say, too, that when we are ill it can feel good—especially when medical remedies aren’t satisfying—to give some of our suffering to others, to make it just a little bit their fault? Suffering would speak, like a virus, in a language of silent codes that replicates itself through how a suffering person makes the people he or she loves suffer. The caretaker’s sympathetic response would become, over time, a source of chronic pain. “Makes” implies action—the sick person spreading their suffering around. I don’t mean that. I don’t mean W wanted me to suffer.

If it is funny to tell a story that says I tried to poison the man I loved, it is because this story lends a pleasing shape to how we fell apart: something rectangular and papery, leaking from the corners but basically sound, as blameless as a bag of flour.

No, I did not try to poison him. But I would not stop baking.

Whole Wheat Pie Pastry

Yield: pastry for one double-crust pie

To make flaky piecrust with whole-wheat flour, appreciate that whole-wheat flour is like coffee: it tastes enormously better when freshly ground. So, first, buy a wheat grinder and a bag of soft spring wheat. Second, grind the wheat. Two and a half cups of ground flour will do. Add 1 tablespoon sugar and 1 teaspoon salt, and mix. Third, make a mixture of ½ cup cold water and one egg yolk (save the egg white to glaze the top of the pie before baking), beat to combine, and freeze while you prepare the rest of the dough. The proteins in egg yolk will help this crumbly dough roll out and add tenderness and richness, though the dough won’t be short on richness, because, fourth, cut 1 cup chilled unsalted butter into ½-tablespoon-sized chunks and rub them into the flour until the mixture resembles chunky cornmeal, with some pea-and almond-sized lumps of butter-flour, the flour and butter not combined—not exactly—more like containing each other. Fifth, pour the icy yolk-water over the dough a little at a time, and toss by hand to distribute the moisture evenly. When the dough just comes together, stop adding liquid (there will be some left over), stop tossing. Sixth, gather and quickly press the dough into two thick discs, cover them, and refrigerate for 30 minutes. Seventh, roll immediately, after dusting your rolling surfaces and pin with all- purpose flour. Pie dough left in the fridge overnight will become hard and stubborn and impossible to work with. Finally, eighth, adjust your expectations. This dough won’t roll out as easily as dough made with all-purpose flour, and when it’s baked, its flakes will crumble rather than sheer. It will taste nutty, cookielike, especially if the flour is fresh.

Excerpted from THE BOOK OF DIFFICULT FRUIT by Kate Lebo. Published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Copyright © 2021 by Kate Lebo. All rights reserved.

An onomatopoetic term for an A-B-C book, with one alphabetically-arranged page, chapter, or section per letter. ↩

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.