Visiting the Ghosts of Bread

Reher's Bakery

Table of Contents

Ever since I—Amy, the bread fiend—discovered the Reher Center for Immigrant Culture and History in Kingston, NY, I’ve been excited. This former bakery gives tours of a retail and baking space that was active for nearly a century. The museum also hosts exhibits that look at immigration from historical and contemporary perspectives.

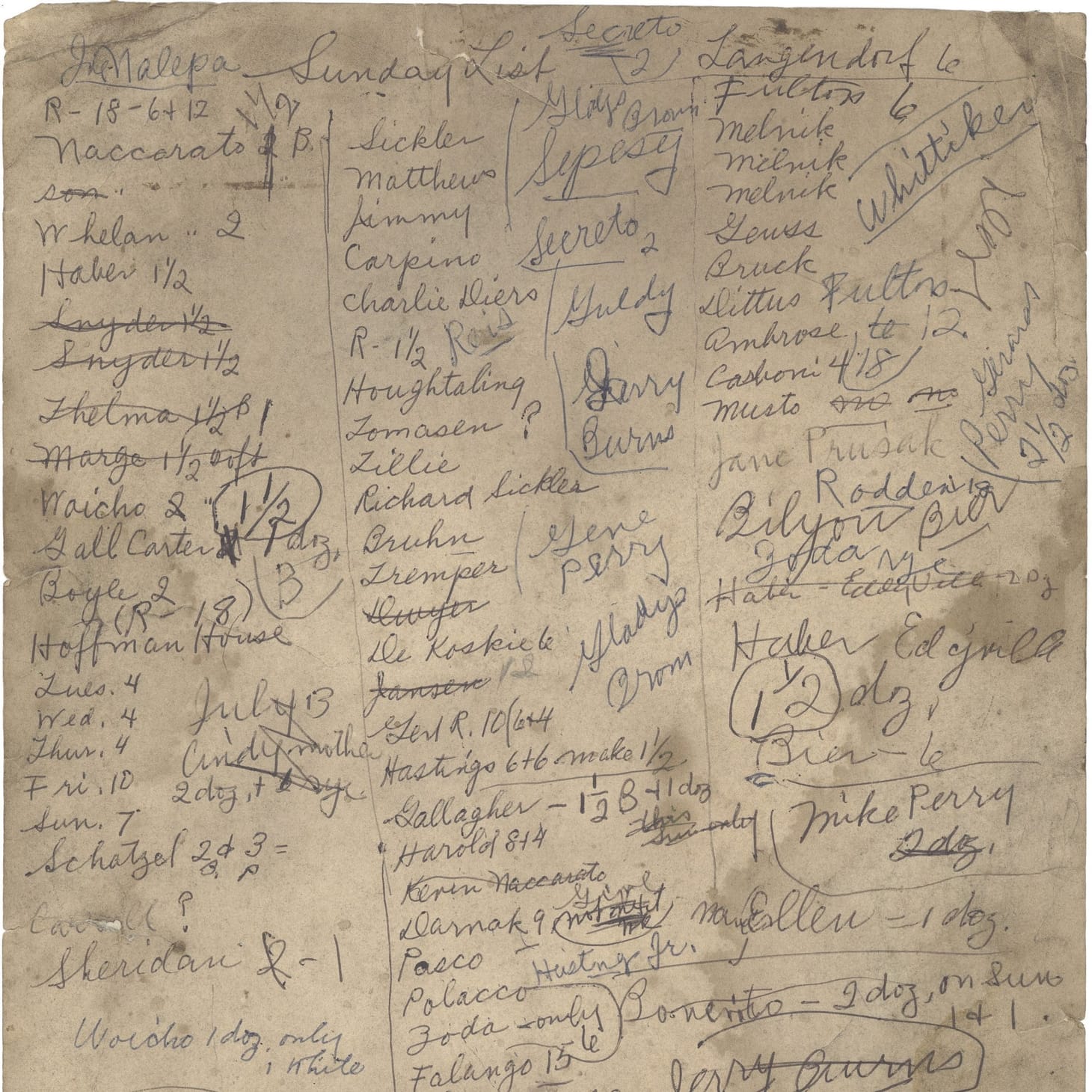

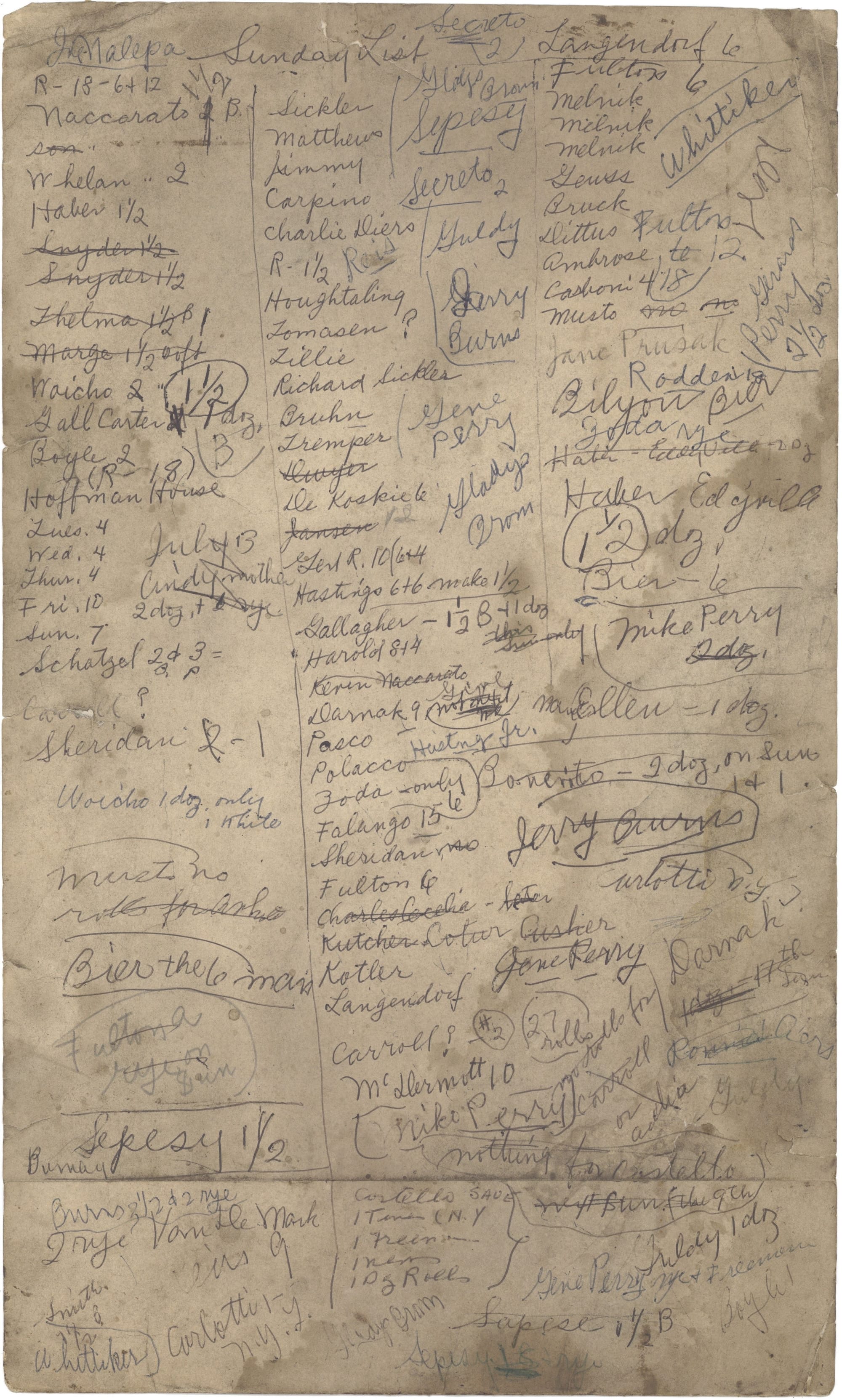

The Reher family ran their bakery from 1908 through the early 1980s and donated the building to Jewish Federation of Ulster County. Among the building’s artifacts is a handwritten list of families who picked up rolls Sunday mornings. Organized by the times church services let out, the list has names, some numbers, and a few capital Bs to indicate a preference for rolls with bumps, rather than smooth tops.

When I took the tour in 2022, the guide was a woman who grew up going to Reher’s, and her family’s name was on the list. I can’t remember if her family liked bumps or smooths, or if she had bacon and eggs on her kosher-made rolls—but that was a common habit, and an interesting culinary collision. I got a good sense of the Orthodox Jewish family that ran the bakery, and how they intersected with the neighborhood they served.

The rolls helped the business survive the rise of factory baking. Another product that helped was rye bread, which Reher’s delivered through the city, and into the famous summer resorts in the Catskills.

In February, I led a conversation about that bread, and many other things rye in a lively event with The Reher Center and The Neighborhood. Food historian and author Andrew Coe and Jewish food scholar/rye bread entrepreneur Avery Robinson were with me that night, and early in April, we met in Kingston.

Our job for the day was to help the center think about how the history of bread could inform further storytelling. Reher staff led us through the tour and told us how people responded to different elements. We started in the storefront, which has shelves with different canned goods, and a life-size cutout of Sadie Reher, one of the sisters. We learned about oral histories that help root the tour.

For instance, Willie Reher was the oldest brother who was responsible for shoveling coal. In an oral history, his nephew Sy Cohen recalls watching Willie shovel the coal. In other interviews, neighborhood children speak of shoveling coal for the Reher's, and how the sisters liked to ask kids questions when they picked up bread.

The museum is in the process of making a display reflecting the bakery as it would have been when it opened in 1908, so we talked about possible breads for the window. We talked about ingredients and processes—the bread would not have had dairy, to keep it kosher. Avery pointed out that kosher verification would have been casual, just an agreement between the bakers and the rabbi, rather than a formal process.

The bakery room has a huge brick oven, a mixer, and a couple of troughs on wheels topped with boards, that’s likely where the bread was shaped. There’s no refrigeration, so retarding dough would not have happened. The mixer was bought in the 1940s, as business in the Catskills grew. The only evidence of a dough divider is a pamphlet, and that could have been just a sales pitch, not proof of purchase.

We tried to visualize the room in use, walking through the making and baking of rolls and breads. The Reher family would not have worked on the Sabbath, Saturdays, until sundown, and board member Andrea Del Cid, whose family runs a Guatemalan bakery in Spring Valley, led us through a baking day, starting in the middle of the night, to suggest a parallel.

We had lots of ideas for how to make the bakery process come to life. A few props, like a peel and brush, and maybe a small, strong toaster oven to make loaves of bread and fill the room with the perfume. Maybe a rolling rack to hold trays and strap pans? Emphasize the dense, immigrant breads that were likely made, in contrast to the fluffy white—American—breads. Eventually, have cooking classes!

It was a satisfying day, to talk about breads and baking with other bread-obsessed folks. I’ve heard that our gathering was very useful as Reher’s considers how to integrate our suggestions, and what to add to tours in the future. The center is under renovations, delaying tours until July, but be sure to sign up for their mailing list to get alerts—and put this Hudson Valley spot on your bread tour this year. In the meantime, take a look at the digital exhibits on their archives to learn more about one bread place.

Another way you can participate in this effort is to nominate a bakery that models the community spirit of Reher’s to be “Reher Recognized.” Take a look here for more info.

Do you know of other museums that are telling the story of bread? Please tell us!

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.