The Story of "The Story of the Staff of Life"

Amy Halloran on the moment that Americans abandoned homemade bread for factory loaves

Table of Contents

As I mentioned on Monday, today we have a guest post from my friend Amy Halloran, better known to the wider world as The Flour Ambassador. When Amy mentioned that she was working on a story about the early 20th-century American transition from an era of mostly home baked bread to one in which most bread was produced in factories (one that we remain in to this day, the efforts of lockdown hobbyists notwithstanding), I knew it would be one I’d want to share here. And thankfully, she agreed.

It’s the story of the National Association of Master Bakers, a trade group that was formed to promote the interest of professional bakers, and a booklet called “The Story of the Staff of Life”, written to convince “housewives” to give up making bread at home. (It’s a cringy little pamphlet, as the excerpts included below should make clear.)

Take it away, Amy, and thank you for sharing this with us all.

—Andrew

I love bread. Homemade, bakery made, even factory made that echoes the Freihofer’s loaves of Canadian Oat I adored as a kid. However, my love is complicated by the idea that bread should be homemade, an American obligation that’s been around for a long time.

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, domestic tasks left the home and began to enter the marketplace. These changes caused anxiety, especially about what went into food and who made it. Sylvester Graham, a social reformer best known for inventing a type of cracker that has nothing in common (except a name) with what goes under our marshmallows, incited a riot in 1837 by stating that public bakers and butchers could not prepare food with health, safety or love – only mothers could do that. He wrote an entire book on the topic, A Treatise on Bread and Bread-Making.

The adjective public was in opposition to private. Moving food preparation out of the home was morally worrisome because someone who took money for a sacred task could not be trusted. Plus, people who were less involved in the manufacture of their food were suspicious of the use of adulterants to cheapen the cost of ingredients.

Graham did not invent the sanctity of bread, but he and others wove a tightknit lore around the importance of homemade bread. Thus as time and technology marched on, and bread baking mechanized and big bakeries became more common, tearing America away from its ideals about our daily bread was a battle.

At the tail end of the 1800s and the start of the 1900s, the battle accelerated. A trade group, the National Association of Master Bakers (N.A.M.B.) formed in 1897, to serve the emerging field. Their records, as well as trade journals from the farming, milling and baking industries, offer great windows into how bread work was changing, and what professionals told each other about ripping the social fabric that wrapped up bread.

The bread decade I study most is 1910-1920, because at one end, more bread was made at home, and at the other, more bread was bought. How did that happen? Reading a digitized report from the 1911 convention of the N.A.M.B. tells me a lot.

This was the organization’s fourteenth convention, and took place over four days in Kansas City, Missouri. After an opening prayer, and a goofy welcome from the mayor, President Paul Schulze made his case for Bakers’ Bread, and against homemade. Schulze was owner of Schulze Baking Company in Chicago, and he pilloried a woman for coming to him with a dense undercooked loaf that she claimed her family and friends loved. He used her as an example of the chief impediment to the advancing of bakery-made bread.

“This country is just full of housewives in precisely that same fix. They are proud of their cooking, and so are their folks, and they think they are doing their duty by baking at home. Their kitchen equipment is such that they can’t possibly bake a big loaf clear to the center without burning the outside. Their ovens, like those of all kitchen stoves, are incapable of developing the proper temperature, and are devoid of the necessary moisture. The long-suffering stomachs of their families continue to pay the penalty of their mistaken sense of duty. Hundreds of thousands of wives and mothers are wondering today why their folks have so much trouble with indigestion and dyspepsia.”

This generation of American housewives, Schulze said, hadn’t noticed that the baking industry was advancing, and didn’t know that their ovens did not possess “the germ-killing power” that modern bakery ovens did. Ignorance and traditions were interfering with progress, but advertising could promote a natural transition to buying bread. The final paragraphs of his speech clearly define how professional bakers could win:

“Keep your own house in order by saying that every baker you come in contact with is working for cleaner and more sanitary surroundings, and go after your competitor hard and fast, your only real competitor – the housewife.

There is a world of romance and human interest in the staff of life for which the whole human race struggles and toils, and the men who find a way to “cash in” on this will be about the truest benefactors the baking industry could have.”

In other words, we were already advertising bread to ourselves. Bakeries just needed to capitalize on that romance.

But this wasn’t the news that traveled far beyond the convention. His claim that home baked bread was dangerous was so brash it reverberated to the pages of the New York Times, and into milling circles, too; millers worried that if people stopped making bread at home the need for small regional mills would disappear!

At the convention, Schulze’s voice was just the first to promote a full on campaign to wage the war for housewives’ (their term, not mine) cash. The only female speaker, a pioneering advertising writer, said, “There was an old argument that advertising bread was too much like using newspaper space telling folks to breathe. But the humor of that idea sounds greater than it is. The creation of the desire for bread is, to be sure, unnecessary, but we must create the desire for the right sort of bakers' bread; we must make a demand for a particular brand with its especial advantages.”

Other speakers referred to a booklet that members could buy and give to their customers. “The Story of the Staff of Life” would help articulate the importance of buying rather than baking bread. It was printed in 1910 and 1911, and perhaps in other years, but I haven’t found any copies of them. Miraculously, I discovered a paper copy of the 1911 edition for $18 (!!) and gave it to myself for Christmas.

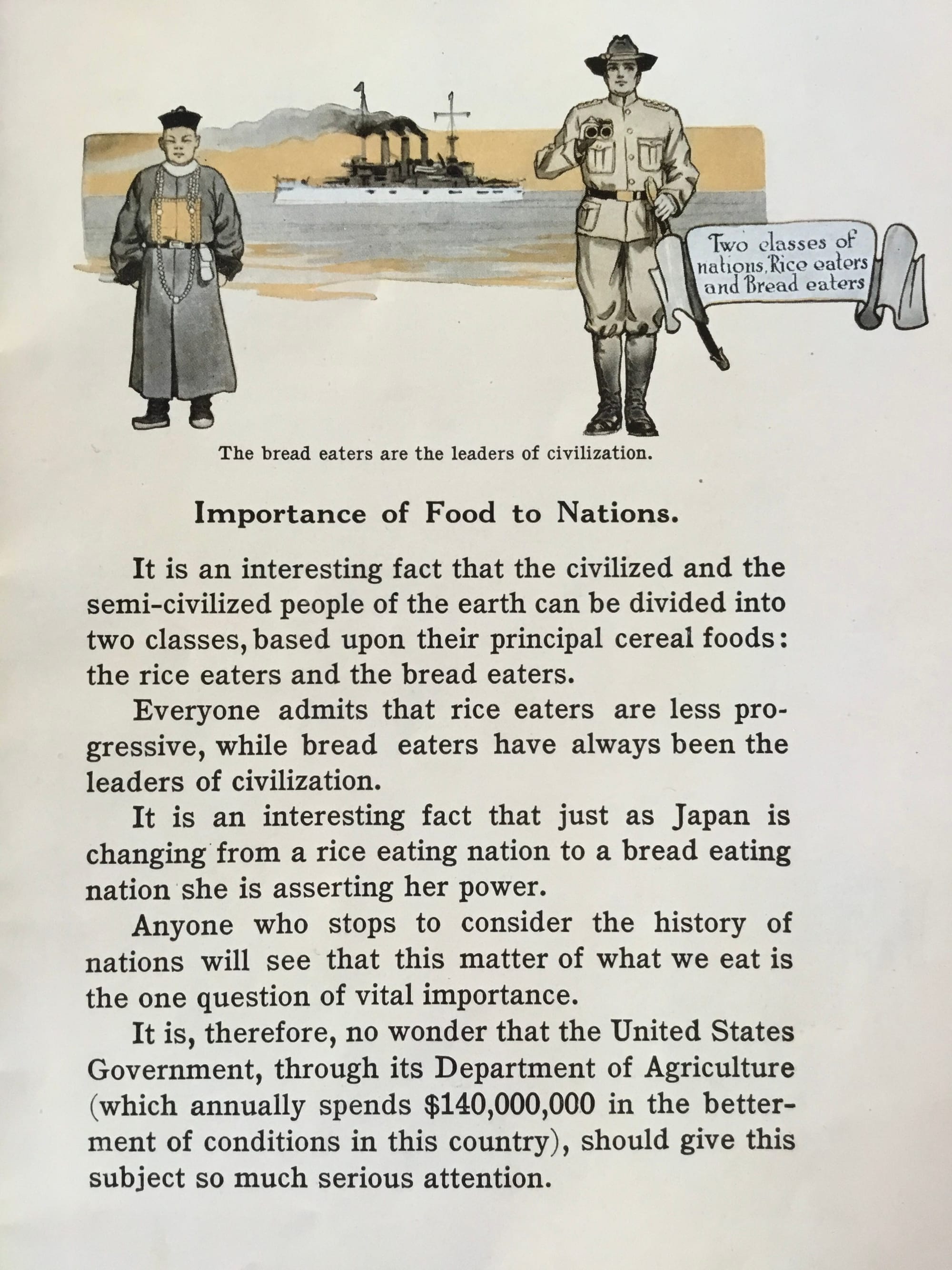

Holding a pamphlet that bakers used 110 years ago to convince people like me to buy my bread instead of bake it is amazing. To see a trade association defame an entire category of food, homemade bread, is surprising, especially considering the arguments gathered in favor of Baker’s Bread. There are racist assertions that bread eating cultures are civilized and rice eating cultures are not!

The narrative also skewers its audience, the housewife, with Schulze’s condemning quote from the convention. Facts and figures from the USDA also argue the case, citing the price per calorie value of bread over meat and other foods. The writing draws in one of the bigger guns in food crusades at the time, Dr. Harvey W. Wiley, now infamous for his mission to make the American food supply safe. Wiley is quoted as saying, “[T]he baking of bread is an art which is most successfully practiced by professionals, and the American method of home bread baking is not to be too highly commended.”

The pamphlet decries the housewife’s inability to attend to bread with the same skill or tools as the ‘specialist,’ and names the prepared goods that women already trust. While the bakeries depicted in the pamphlet are not referred to as factories, the writing lists goods made in canning factories: tomatoes, succotash, asparagus and spinach, soup and “ready-made pickles, preserves, catsup and relishes.” Why not entrust the family bread to the modern bakery?

Finding all these words and pictures about how people talked about bread is fascinating. None of them unravel the obligations we wrap around the gift of bread, but they help explain why feelings about who should make bread are so complex.

For further reading:

Aaron Bobrow-Strain’s book White Bread: The Story of the Store-Bought Loaf

Report of the Convention of the National Association of Master Bakers at Google Books

The Story of the Staff of Life at Archive.org

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.