The dough before the dough

On adjusting preferments in bread doughs

Table of Contents

One of my goals with Breaducation is to make it the sort of book that teaches someone to bake bread without a book—to provide the tools and confidence someone needs to create their own recipes or to make adjustments to recipes from others. To make a person into a bread baker, in other words. At the same time, it has to be a book for those who don’t want this (or at least don’t want it yet)—the recipes need to work as written, without the reader needing to consider the sorts of questions that I did when creating them.

One of the things I have struggled with is striking the proper balance between recipes that are fully prescriptive and separate instruction that gets at the flexibility that is built into bread baking as a practice. As many of you already know, serious bakers use formulas, not recipes.

Both recipes and formulas are comparable to musical scores—instructions for the recreation of a dish by another. Recipes are like orchestral scores, where each instrument’s part is delineated in full; yes, there is room for a performer or cook to express themself in the performance, but all of the notes are there on the page. Meanwhile, bread formulas are closer to jazz charts, shorthand frameworks with only the cord changes, key, and tempo provided; improvisation and interpretation are mandatory, and essential to the magic of the thing. Breaducation will contain recipes, but it will also hopefully teach you to see the formulas within them, so that you can start creating ones of your own.

A perfect illustration of this tension is in the question of preferments, the “dough before the dough” that many formulas include. In a preferment, a portion of the flour and water gets fermented—with yeast or a sourdough culture—ahead of the final dough. Not all yeasted breads have a preferment, though many of the best ones do; all sourdough breads do, of course, because the levain is the sole source of fermentation, and it must be kept alive and happy even when you aren’t baking with it.

An approachable recipe tells you exactly how much flour, water, and yeast or sourdough starter goes into the preferment, and how long it will need to ferment at a specific temperature. But a nimble baker is free to make changes to the preferment— more or less water to change its flavor profile or performance, more or less yeast or sourdough to adjust the time it takes to ferment, more or less preferment overall to adjust the time the final dough takes to ferment—without significantly changing the resulting bread.

When I write a recipe/formula for myself, the preferment part is always fluid: One day I might use less starter or yeast to have it ready the next morning, and another I might use more, so that it is ready in just a few hours. Ditto for the final dough: If I have the time, I’ll use a modest amount of levain and let the dough take all day; if I am rushed, I’ll make more levain so that the dough moves quickly. Each of these approaches work great, and it means I am able to easily adjust things depending upon when I have time to do the work and when I want the bread to be ready.

But for the recipes in the book, I need to pick a lane—to give exact amounts and proof times for a single preferment with each one. Deciding which to include among the many possible options is challenging, but I think I am going to have most preferments proof on a 12-hour schedule: start it in the evening and have it ready the next morning, leaving the whole next day to make the final dough and bread. Elsewhere in the book, I explain the hows and whys of building preferments, and how to take any one of the recipes that follow and make adjustments depending upon whatever goal (or schedule) you have in mind.

Increasing or decreasing the amount of preferment in a dough is pretty straightforward: You just adjust the amount of it and add or subtract the identical amounts of flour and water from the final dough. And when a preferment is 100%-hydration—equal parts flour and water by weight—it’s simple enough that you can even do the math in your head.

But not all preferments are 100%-hydration, and there are advantages to using other hydrations. A liquid preferment will proof quickly, and it tends to confer lots of extensibility to a dough, thanks to increased enzymatic activity. Liquid preferments are thus great for doughs that require lots of manipulation—baguettes, pretzels, bagels, stretched or rolled flatbreads, etc.

Stiffer preferments proof more slowly, and they provide the flavor and acidity of a preferment without adding extensibility, in the case of doughs that might need more strength and structure. They are also less enzymatically-active, which makes them a better choice when a dough contains a significant amount of whole-grain or high-extraction flour, both of which are already rich in enzymes; using a stiff preferment in an already enzymatically-active dough provides some restraint, preventing it from proofing too quickly or becoming overly slack.

With the proper technique, a liquid preferment can work fine in a dough calling for a stiff preferment, and vice versa. And if you are new to baking, it is worth trying both side-by-side in the same formula, so you understand what happens when you use one or the other, and so you can decide which you prefer. Swapping out one hydration of preferment for another is also no big deal, though the math is a little more complicated, because you first need to determine the ratio of flour and water in it, then adjust the final dough accordingly.

I can do all this math pretty quickly on scratch paper, but I kind of hate it. And the formula-building spreadsheet I use—which I adapted from someone else—is a little wonky when calculating the impact of sourdough preferments on the final dough formula. It gets close enough, but can introduce annoying (if mostly minor) errors.

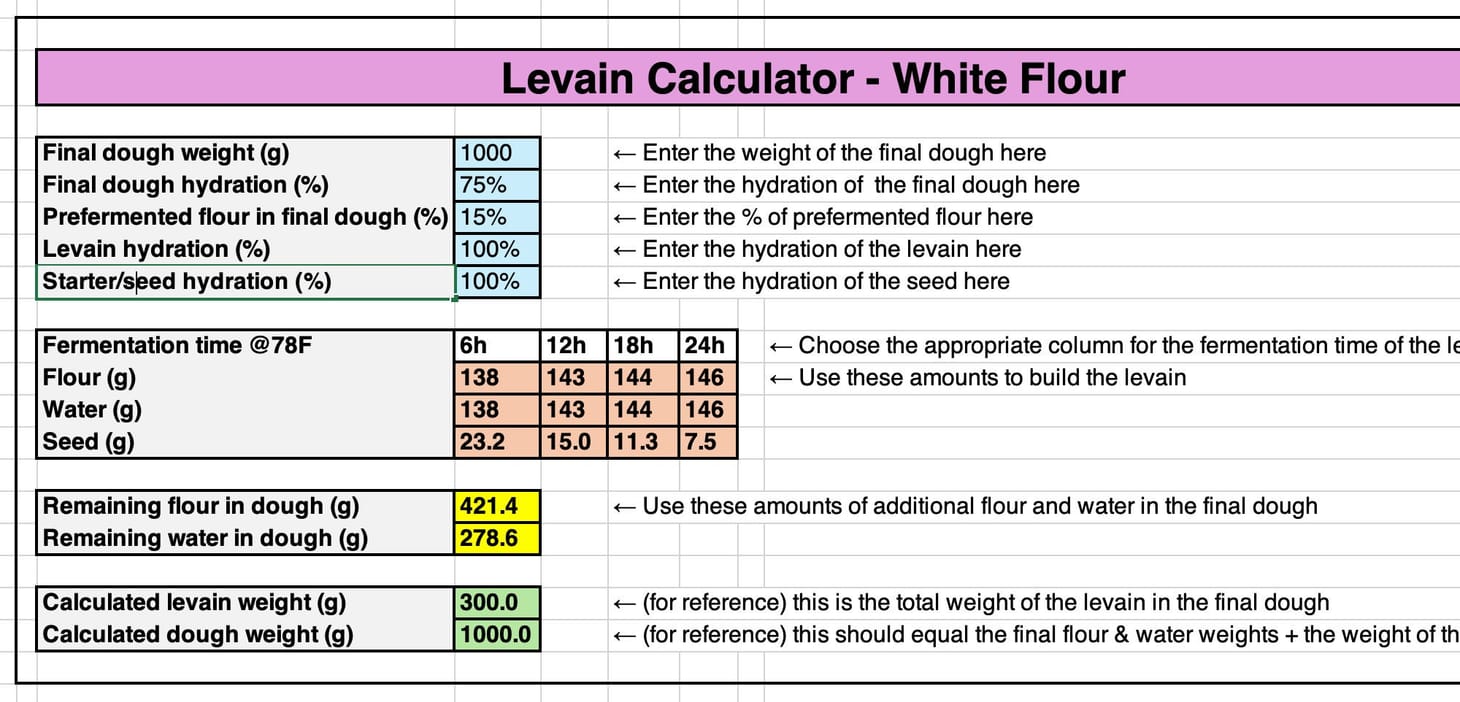

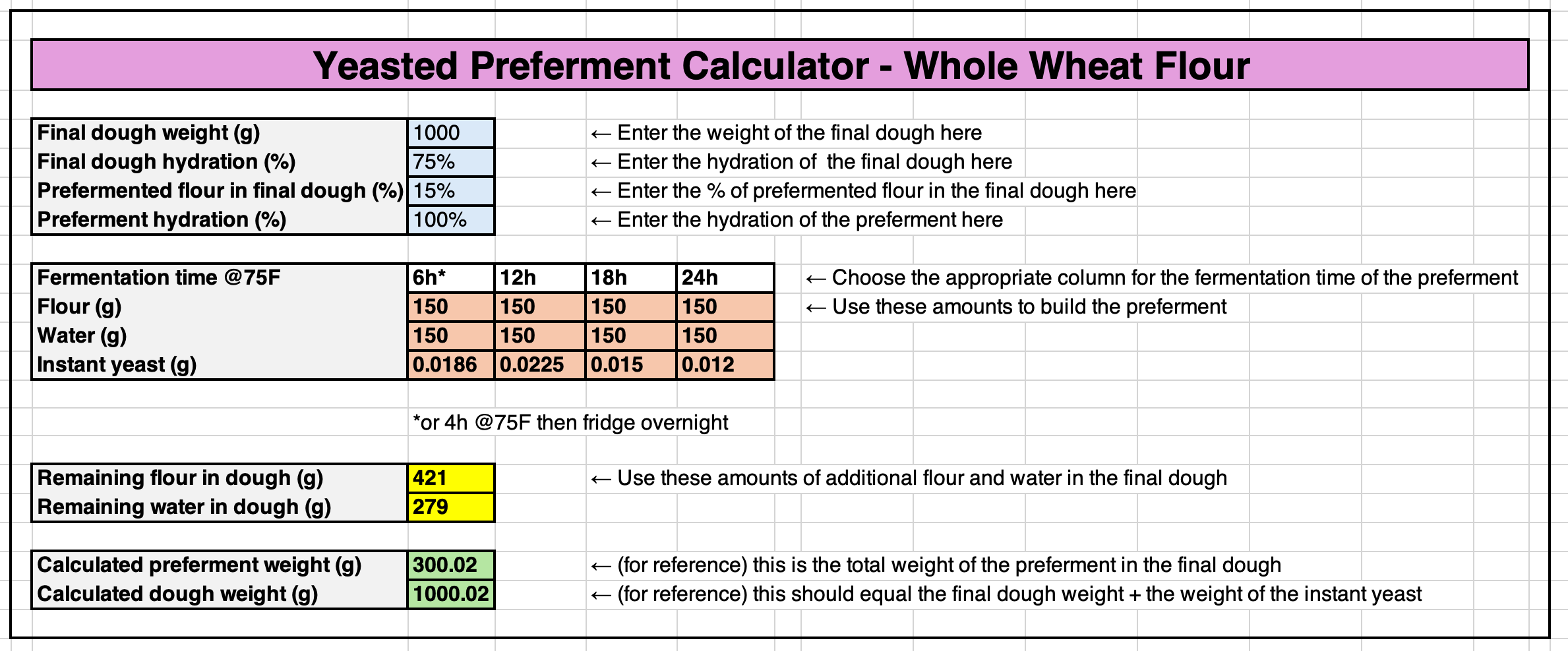

So I set out recently to build my own preferment calculator. Or rather, a series of preferment calculators, covering both sourdough and yeasted preferments. I wanted them to spit out numbers not for just one specific proof time, but for multiple different times all at once, so that it’s simple to determine what to use depending upon the time I have, with the underlying numbers baked-in, so I didn’t need to think about how much yeast or starter to use. And—because whole-grain flours ferment more quickly than white flours, requiring a reduced amount of yeast or starter—I needed to create separate sheets for each.

(Another reason I built these is because—as I shared with my Breaducation testing group—I’ve recently I’ve started maintaining my starters at a stiff hydration, so it is useful to have a calculator that can easily account for the reduced amount of water in the seed.)

In other words, it’s the perfect set of spreadsheets for someone who has recipes from someone else they’d like to fiddle with, but don’t know how or don’t want to calculate on their own. Maybe even some future person with a book called Breaducation on their shelves—the book will aim to give them the skills and knowledge to make changes on their own, but the spreadsheets will make it easy to dip their toes in the water.

These are works-in-progress, but they do work, and I’d love to get some people playing around with them, so I’m going to share them with paid Wordloaf subscribers (for the time being, at least) in a separate post, along with some insight into how I made them and instructions on how to make them work.

—Andrew

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.