The biggest secret that is not secret

An interview with Addie Roberts, author of 'Secrets of Open Crumb'

Table of Contents

While I like to say that I’m not all that invested in the idea of chasing an “open crumb” in my breads, I’m also not immune to the beauty of a pearlescent, lacy bread when it appears in my feeds. And thought I don’t necessarily consider an open crumb an essential element of a well-made bread, I’m very much interested in how one achieves it, all the more so now that I am writing a book on bread baking.

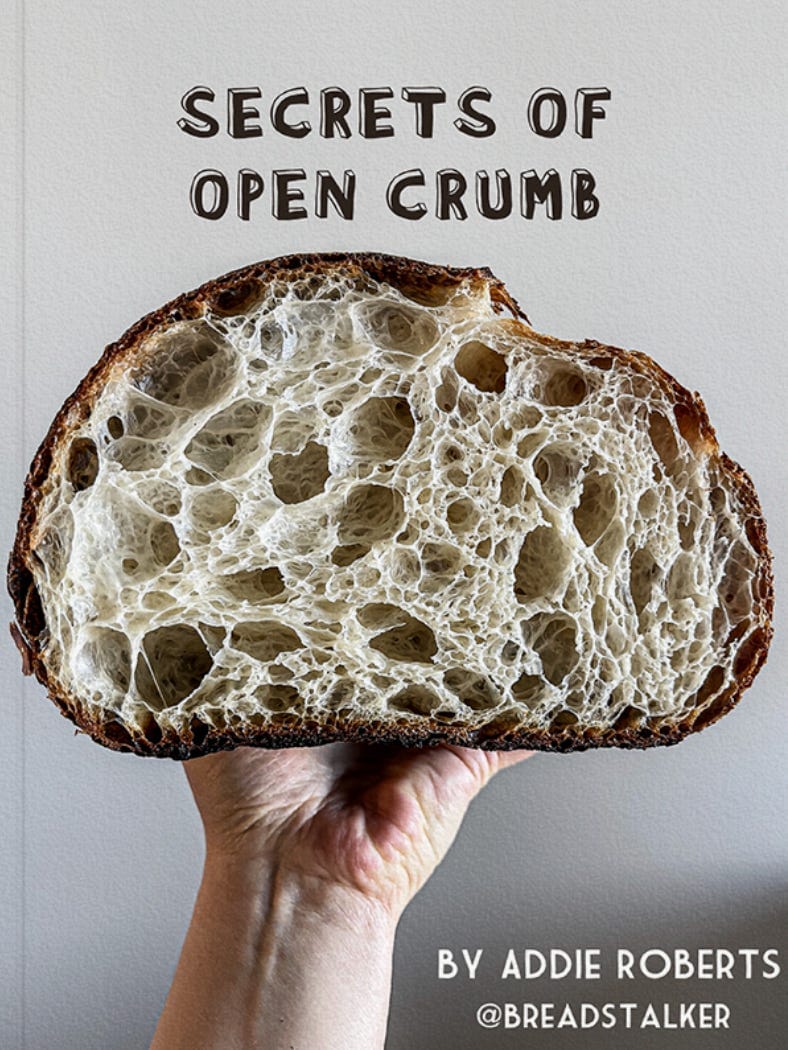

One of the undisputed queens of open-crumb baking is Addie Roberts, who goes by @Breadstalker_ on Instagram. Almost every day she posts images of gorgeous, impossibly lofty loaves, with intricate, maze-like crumbs and deeply burnished, glossy crusts, along with extensive information on how she gets them. She clearly loves baking bread, and shares her knowledge and experience freely with her many followers. She’s also collected many of her approaches in a digital book called Secrets of Open Crumb:

I recently sat down with Addie to talk about the book and her work teaching bakers all about well-fermented bread. To her, open crumb is not a goal, but rather a byproduct of proper fermentation, both in the starter and the dough itself.

My main desire is to teach people how to make well-fermented bread. I want nothing more.

I’m grateful to her for taking the time to share some of her bread baking knowledge with us all. I hope it will prompt you to get her book and explore it in much more detail, and to follow her work on Instagram, whether or not you want to achieve open crumb in your own breads. And don’t miss the recipe she shared with us for her “touch-of-soft-wheat sourdough”:

—Andrew

Andrew: I think most people who are familiar with your amazing breads on Instagram and elsewhere might be surprised to learn that you didn't start baking until fairly recently. Is that true?

Addie Roberts: Yeah, in 2019.

AJ: Okay, so how did how did that come about? How in a few short years did you come to the point where your breads are as beautiful as they are?

In 2019 I wanted to learn a new craft, and the first thing that came to mind was bread. At that time, I was learning Italian, but eventually I had to quit because bread just took over. I first I started learning and baking with yeast. And then I heard about sourdough and how complicated it was to do, and to maintain the natural occurring fermentation of a starter. I was immediately attracted when I heard that it's complicated and that it takes a lot of work.

I started reading a lot of bread books, starting with the Tartine books. And I read them as if I were reading a novel or a poetry book—I even read the recipes and the ingredients, through everything. Then I found other books on bread science. Anything that I could find, along with, of course, everything online that I found through Google.

I started a starter [from scratch], but I followed general guidelines, like that the accepted ratio was 1:1:1 or 1:2:2 for the maintenance of the starter. But the more I learned, [the more I realized that] my bread was under-fermented in the beginning. [I realized that] I was rushing through the process. When we bake with yeast, you know, the dough is ready in two or three hours, the fermentation is fast. [But] with my sourdough, it's been four hours, and I'm looking at the dough and nothing is happening—I don't see the same dough as when I'm baking with yeast. But I would shape [the loaf] because that’s what [I’d been] told through reading and websites. [I thought,] I have to shape it now, even though my eyes are telling me differently that this dough is not well-fermented. So I would end up with under-fermented bread all the time. This is how I started to learn more about starter maintenance—how to properly balance it, that it is very important to balance your starter.

The more I baked, the more I learned and the more obsessed I got. I started applying different things from all the books that I read, all the knowledge that I gathered, and I [began developing] my own ideas that made sense to me, like that I have to do things to my starter in order to to make the it perform better. And little by little, that's how I developed that style of baking.

I said, What is open crumb? I had no idea that that “open crumb“ existed, I didn't know what it was. But when I saw pictures of open-crumb bread, I said, Oh, this is the bread. I want to learn to make this kind of bread. Just from looking at pictures of the texture of those breads.

[Eventually] I found all these amazing bakers on Instagram, like Kristen Dennis and Trevor Wilson. And I saw that Trevor had a book on open crumb. I said, What is open crumb? I had no idea that that “open crumb“ existed, I didn't know what it was. But when I saw pictures of open-crumb bread, I said, Oh, this is the bread. I want to learn to make this kind of bread. Just from looking at pictures of the texture of those breads. So I read Trevor’s book Open Crumb Mastery. And that's how I got much deeper into it. And here I am today.

AJ: Your book and his are complementary in a way, because they each give different a different set of instructions for how to achieve an open crumb. His focus is more on dough mechanics and manipulation and the way that you do certain types of techniques, like folding and bulk fermentation. And your focus is more squarely on starter maintenance. So it's interesting that you used his book as a starting-off point, but you came to a different set of instructions for teaching people how to get to a similar style of bread.

I've read through your book a few times now, and tried to pull out what I think are the key techniques that people should focus on if they want to achieve an open crumb, and I wanted to go through some of those with you. To begin with, can you tell me how you take care of your starter and how you came to that method? What is it you discovered when you started doing things that way?

When I was doing the accepted 1:1:1 or 1:2:2 [feeding] ratio, I was told to feed it just once per day. And my apartment is very cool, like 68-70˚F. So I was keeping the starter at this temperature and feeding it with a very low ratio, and it just it wasn't giving me [good] results. And then I learned that a starter should be fed at least twice per day, not [once] every 24 hours. If I was going to do a feeding every 12 hours, that meant [I needed a] higher ratio, to give it enough food to last for 12 hours. I started with a 1:3:3 and 1:4:4 ratio just to see what worked for me on a 12 hour schedule, with my flour and my temperature.

I [soon] discovered how important temperature is—68-70˚ was too low, so I bought a proofer that maintains a constant temperature. I started keeping it there, and I discovered that the [best] ratio for me is 1:6:6, [or] 10 grams starter, 60 grams flour, and 60 grams water. That ratio worked [best] for me with the flour that I was using, flour I bought from the grocery store, but bread flour, not all-purpose.

That’s another thing I discovered. In the beginning I was feeding my starer with all-purpose flour. When I switched to bread flour, I noticed that the starter would behaving much better—it maintained its peak longer and it rose higher. (Of course, rising also depends upon the condition of the starter, not just the flour [you use].) So this was how I came up with my ratio of 1:6:6, feeding it every 12 hours and keeping it at a constant 75-76˚F. That’s when I started seeing results.

[Then I read the] wonderful book Bread Science, by Emily Buehler. I developed many of my ideas [from reading] that book. Like stirring the starter [while it proofed]. Not aimless stirring, but giving it [actual] folds. I started treating my starter as a mini-version of my dough.

If it is important to build structure and develop the gluten in our dough for it to trap more gas during fermentation, [it made sense to do the same with my starter]. So I started doing mini stretch-and-folds in my starter with my spatula to develop the gluten. But I also learned [from Emily’s book] that stirring is also useful to introduce a little more oxygen, to keep the yeast happy.

[It’s the yeast] that leavens our dough, but it coexists with lactic acid bacteria. Lactic acid bacteria are much faster growing than yeast, and they can easily outgrow and outnumber the yeast, which can create an imbalance in the starter, and the yeast will stop reproducing and producing CO₂.

We are taught, Wait until the dough doubles [in volume], but not with a sourdough starter, only a bread [dough]. It's a different process. So I learned that just doubling the starter was not good enough, it wasn’t strong enough. [If the starter] is barely or only doubling, this represents weakness.

[With my current process], when I prepare a levain from my main starter, it rises five or six times in volume. And that is because I have actively healthy yeast, [which comes from] giving it more oxygen with stirring and developing its gluten.

But this also encourages the production of a little bit of acetic acid. It is the homofermentative bacteria that outgrow and suppress the yeast and [create an imbalance in] our starters. The other bacteria [in sourdoughs] are the heterofermentative, which are the ones that we want to encourage in our starter. (All of this is explained in my book in detail.) I also learned a lot about pasta madre, the very low hydration starter that bakers used to make pannetone. And through those teachings, I learned how to take care of my starter even better.

AJ: I thought it was interesting that you said that you found that you get the best results when you proof your starter at 73-75˚F and that you needed to use a proofer for that—you had to warm it up to get it to that point. Since you live in Florida, you must have air conditioning on all the time. You have the opposite problem of many people, which is—especially from June to October or so—things are often too hot. Maybe if you had lived somewhere else, you wouldn't have figured that out because you didn't start off in a in a too-low place and you might now be proofing your starter at 78 or 82˚F instead.

Actually, I first got the proofer before I learned about homofermentative and heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria. When I first got my proofer I was keeping my starter at a 1:1:1 ratio, at 80˚F, and it had a runny texture, not a tight [one]. When I learned about these two kinds of bacteria I said, Okay, in order to create a balance by not encouraging the homofermentative bacteria to take over—they are encouraged by hot temperatures—I need to keep the starter at a lower temperature. And that's how I also raised my ratio, and found out that 1:6:6 works for me at 75˚F.

AJ: I think a lot of people might be surprised to know that even a four or five degree Fahrenheit shift down or up would make a big difference.

Even one degree makes a big difference, yes.

AJ: Do you know Dan Leader, the founder of Bread Alone bakery [in upstate New York] and his book Living Bread? In it he also talks about stirring the starter during the first few hours of fermentation. Whether it's an old tradition or a recent one, it’s definitely confirmation of your thinking that it's a good idea to oxygenate your starter as it proofs, to supercharge the starter and boost yeast activity.

I read in a book about how to make a starter from scratch that for the first 24 hours you don't have to do anything except stir it once, and that's how I started doing it. But little by little, the more I read, the more I learned about the two kinds of bacteria that are very important for us to keep an eye on. And to introduce a little bit of the acetic acid through that oxygenation, which is produced mostly by the heterofermentative bacteria.

AJ: What is your understanding of why the acetic acid is in the right amount is good for the starter and the bread?

So lactic acid represents weakness—too much build up lactic acid breaks down the gluten and it suppresses the yeast. That's why a starter only doubles in size. And acetic acid is the opposite: It gives more of a leathery structure to the starter and the dough. Too much of it is not good, and it will take away from the flavor of the baked bread. So by keeping it at a lower temperature, at 75˚F, I'm not allowing the homofermentative bacteria to take over. So [stirring the starter and proofing it at a slightly lower temperature] encourages heterofermentative bacteria. [What I’ve learned from studying pasta madre is that these] are the most suitable bacteria for baking. That's why a little bit of acetic acid in the maintenance of the starter is a good thing.

AJ: Can you talk about the benefits of using a starter at its peak activity? From the book, I take that to mean when it has expanded as much as it's going to and is maybe just starting to collapse.

[From my readings] I was taught that I have to use it at peak [activity] because if I missed that stage, it would not leaven my dough well. So I would use it way too early out of fear that I would use it too late. But I ended up using a starter that was immature and not active, and I would end up with under-fermented bread. That's how I started using it a little later and a little later, [until I learned what peak activity in a starter really means].

AJ: I feel like it's important to tie that idea into the bulk fermentation too, since it seems like your instruction and your approach is to push bulk fermentation quite far compared to what other people do. So tell me how you came upon that idea and why you feel like that's really important for getting open-crumb breads.

When I was learning, my first bakes were always under-fermented. Most of the reason for this was because of my starter—it wasn't well balanced and it was weak. I started just visualizing how a dough looks [when made] with commercial yeast, how puffy and big it is [compared to how my dough] with a sourdough starter looked. Even after five hours, my sourdough [didn’t] look perfect and big like yeasted dough did. I started thinking, Okay, let me wait a little longer. And that's how little by little I started [extending my bulk fermentation].

To me “open crumb” really means well-fermented bread.

I also stopped comparing my doughs to other bakers’ doughs. I would do six hours bulk fermentation because I read somewhere that his or her bread took six hours to ferment. But then when I’d look at my dough after six hours, it didn’t look ready yet. And I would end up with under-fermented bread all the time. So I little by little I would push it 30 minutes more, 30 minutes more, 30 minutes more. And I noticed that the more advanced the fermentation was, the better fermented the bread was. To me “open crumb” [really] means well-fermented bread.

In the sourdough baking community, bakers talk all of the time about [the dangers of] over-fermentation, but nobody [really] talks about under-fermentation. I think that's why people end up with under-fermented bread—because they're afraid of over-fermentation.

My followers are constantly saying to me, I want a crumb like your crumb. The only way [to get that is through] optimally fermenting the dough—that's why I like to push fermentation further. I know that next time [around], I can make adjustments, I can [ferment it] less. But once you’ve found the flour that you use on a daily basis, you will know how it performs and [whether] it can handle long fermentation. And then you will know how to make adjustments.

AJ: Do you proof your doughs at a similar temperature to that you do your starter, 70-75˚F?

Yeah, 70-75˚F, always.

AJ: So a lower proofing temperature will also mean the dough takes longer to fully proof.

Yes. It makes sense that at a lower temperature it would take longer, and also means that you shouldn't be afraid of over-fermentation.

AJ: Right. Since you mentioned flours, in your book you use lots of different flours. I kind of love the way that the book is just a collection of your favorite recipes, a series of recipes that you make. There's no rhyme or reason other than these are formulas that you use and love and that work well. I'm wondering how you how you choose the flours you do and if you feel like the flours you use are one of the keys to getting the results that you do.

Yes, definitely. I use flours that I buy from the grocery store and are easily accessible, especially for feeding my starter. I have discovered which one works best for me and and can find all the time at the store, a bread flour with 12-13% protein. I have tried making a starter with flour with 11.5% protein, and it was fine, but I had to lower the hydration to 80%. With 100% hydration, it wasn't maintaining a peak very well and the texture was more runny. That's why I've chosen to work with 12-13% protein for the bread as well. Of course you can achieve an open crumb with flour of 11.5% protein, if it's a good quality flour. And if the starter is maintained properly. If you give enough time for bulk fermentation, you can definitely achieve open crumb with a lower-protein flour.

AJ: So you don't necessarily feel like you need to be using specialty flours of some kind? The strength of the flour is more important than some specialty flour that you can’t find at a supermarket, for example.

Yes, exactly. Unfortunately, there are some people who complain about [the false idea that] in order to achieve open crumb, [all you need is to] get yourself a very strong flour. This is not true: Open crumb is all about fermentation, which comes from a well-maintained starter. [You don’t need] “stupid, strong flour,” as they call it, to achieve open crumb, if you understand the process and how to maintain and balance your starter and what's going on inside the jar. It’s all about fermentation.

AJ: I’m interested in your use of egg yolk in your starter, and whole eggs in your dough. Tell me how you landed on those approaches.

The egg yolk I found so fascinating while I was learning about pasta madre. And from the book 4.1, which is written in Italian. An Italian Baker friend of mine gave me some translated pages [from that book] on the most important things to know about pasta madre. It suggested that if the mother is too acidic, you can give it a little bit of egg yolk to absorb that acidity. I was immediately attracted to the idea. I [thought], If it works for pasta madre, it would work for my regular 100%-hydration starter too.

So I treated my starter with a little bit of egg yolk, like four or five grams, for my ratio of 1:6:6 which is 10 grams starter, 60 grams flour, and 60 grams water. And it just it was so sweet in flavor. And I saw the texture of it, and how it performed in the dough and maintained a good pH balance. So from time to time [after that], I would treat my starter with an egg yolk. I was so fascinated with it that for a whole year I maintained an additional starter with with egg yolk and sometimes even a little bit of sugar. And it's just made great bread.

AJ: And you don't differentiate between the kinds of breads that you use that starter in and the ones that you use with your standard starter?

No. I use the egg yolk starter for any bread that I make, and it performs very well.

[As for] adding eggs [to a dough], I just I thought well if I add an egg, it will add more protein to my dough, [to give it] more strength. I tried [adding] an egg one day and I was blown away. It's [especially] good for if you're doing a longer bulk fermentation, the egg adds additional strength, and it keeps the dough in good shape, because you're adding more protein to the dough. And then I started [wondering], What if I just add the egg white or only the egg yolk, or the whole egg? They all gave me amazing results, a beautiful texture and flavor. I wouldn't call it eggy, just a very pleasant, melt-in-your-mouth texture.

AJ: And do you usually use an entire whole egg in the dough and just replace the water with egg?

Yes, I include the egg as part of the hydration. I don't do a precise calculation of how much fat or how much water is in the egg, or in the egg yolk or in the egg white. I just add it as a whole to the hydration.

AJ: So then it's an easy swap. Somebody who's wants to try it out could just take 50 grams of egg and then make up the difference with water in any recipe.

Yes.

AJ: I guess the only other question I have about the book is that I noticed that you do you tend to vary your the length of your autolyse quite significantly. Sometimes it's quite short, sometimes it's very long. How do you decide to do it one way or another?

I am a big fan of autolyse. If I had the time, I’d always do a long autolyse. Where [in the book] it is shorter it’s [only] because I didn’t have time to do a longer one. But if I have the time, I always prefer to do a very long autolyse, because it just helps so much. Not only with developing the gluten—the longer the autolyse, the better the gluten is developed.

I'm attracted [also] to the weakness that the longer autolyse introduces to a dough. A little bit of weakness is perfectly fine, it's a good thing. That vulnerability of the dough will help I think with the oven spring, with the dough blooming in the oven. Because the flour is fully hydrated. The gluten is a little bit broken down, but still strong [enough] to maintain the structure of the dough. And it will be much easier to bloom in the oven, instead of pushing through all that strong, unbroken gluten.

AJ: I love the term “vulnerability.” That's a nice word for it.

People are trying to prove everyday that you can achieve an open crumb even without autolyse. That is fine. Of course you can, if the fermentation is optimally done and is performed by a well-balanced starter. But I personally do [an autolyse] for that length for that reason.

AJ: Just so people understand: You might mix your flour and water for the final dough at the same time that you build your overnight starter, and then the next day you basically just bring them together?

Yes. For example, I usually use my starter straight to make bread dough. But lately because I haven't had the time to mix my dough when my starter is ready, I will [instead] build a levain, and the levain will take around five or six hours to be ready. So while the levain [proofs], I’ll mix my dough for an autolyse, so it too will [last] five or six hours. Sometimes I do it a little later, up to three hours before the starter is ready, which will still be long enough. It's all about good fermentation. This is the biggest secret that is not secret.

AJ: It's maybe a secret that people don't want to see what's right in front of them, because they want some other “trick” instead.

Right. And they are so afraid of over-fermentation. With my followers the only thing that I hear is, But I'm afraid of over-fermentation, I'm afraid of over-fermentation. I see other professionals [pushing the idea] that pretty much every [failed] bread is over-fermented. On the contrary, I see totally the opposite: Most sourdough is under fermented. I don't understand why this is not addressed properly.

AJ: Sometimes if I push the bulk fermentation right to the limit, the dough can be really nice going into the banneton but when I take it out of the fridge, it seems to have collapsed somewhat, and I'm wondering if you you see that or if you understand why that would happen and how someone could avoid it.

Usually if this happens it's a sign of under-developed dough. This doesn't happen to me. Of course, in the beginning it did happen. Because in addition to me not understanding fermentation, I was underdeveloping my dough as well—I wasn't mixing enough and I wasn't doing enough coil folds. So my dough would always [have] a very weak and relaxed structure. Under-developed, weak dough will not be able to trap more gases during the second part of the proofing time. It just doesn't have strong enough body to keep fermenting.

Or it [could be] the balance of your starter. If the starter [contains an excess of] lactic acid, it breaks down the gluten and dough structure, and that's why you might end up with a dough that breaks down in the oven. If [your starter has the proper amount of acidity], it will bring extra strength to the dough while mixing it. But if you add a starter that is rich in homofermentative lactic acid bacteria, it will introduce too much extensibility to the dough and, like I said, this is represents weakness. The dough will be way too extensible. In addition, if you don't perform enough coil folds, and even if you do, the gluten will be already broken by the lactic acid. That’s what happens when the bread breaks down in the oven.

AJ: So everything comes back to proper fermentation.

Yeah. And starter balance. Yeah.

AJ: Do you want to talk about what your new book is going to be about?

My loyal followers ask me every day, Can I have the recipe? Can I have the recipe?, even though in sourdough bread baking, it's more a formula that you make work for your environment, with your ingredients. You should still think of your dough in front of you and treat it based upon what you see.

I won't be asking people to blindly follow what I'm doing. With each recipe, I want to introduce knowledge to educate people, to tell them what I did, [while reminding them to] watch out for this, this, and that. I will guide them through how they are going to bake instead of telling them do exactly this, this, and that, because that may not work, and it would mean my recipe is not good. You should still think of your dough in front of you and treat it based upon what you see.

I also wanted to share with you, because a lot of people have asked me, why my books are [only] digital. I wanted to share a very personal story about this. In 2021, I was approached by a publisher with a very nice offer to write a book about open-crumb baking. Four months into the process I had pretty much written everything, but they told me that they wanted to hire a professional food writer to rewrite it. I was very embarrassed and ashamed that the writing wasn't good enough or didn’t fit the mold of what a bread book should sound like. They even asked me to pay the food writer [to do the rewrite].

So I thought, This doesn't make sense to me. It told me they were not really interested in what I had to say about my style of baking and what I have to offer. I just felt they didn’t really want me to write a book—they wanted my ideas, but written by somebody else. And that wasn't going to be authentic, authentic to me. So, since I already had all that material written, and I was inspired by the bravery of Trevor [Wilson] and how he presented his ideas, I said, What if [instead] I tried to write my own PDF? Since I already have written it all, and I have loyal people who follow me and my ideas and want to bake bread like me? Let me try. And this is what happened, and why my books are digital.

AJ: I'm sorry to hear that. It doesn't sound like a good experience experience to go through, especially for somebody who has such a big following and clearly knows what they're doing. Just to be clear: The book that you were going to write for the publisher is the one that became Secrets of Open Crumb?

Yes. Before the publisher reached out to me, I was writing a short PDF about starter maintenance. And when the publisher made the offer, I just added the written material about the starter to the rest of the material that I’d spent four months writing for them. And when it didn't work out between us, I had written so much already that I braved up to create it as my own digital book.

AJ: Well I hope it's sold many copies. It's wonderful, and I know you have the audience for it.

Yes, I'm so grateful that people embraced it and accepted it so well. And it has [had] a lot of interest, which made me write the second one, with only recipes. But it's going to have the same feel as the first one, offering education. My main desire is to teach people how to make well-fermented bread. I want nothing more.

I also want to make clear that I am not pushing an open-crumb ideology. I’ve received some comments that that my “ideology” for open crumb is actually the poster child for what professional bakers are teaching about over-fermentation. I hate that word “over-fermentation,” while all the breads around me are actually under-fermented because of the pushing of the over-fermentation idea. I'm not pushing ideology. Open crumb is just well-fermented bread, nothing more. And unfortunately, when people hear “open crumb,” they think, Oh, the bread with the big holes. No. Open crumb bread doesn't have to have big holes—usually the big holes come from under-fermentation and bad shaping. So when those examples are given as open crumb, they're just not very good examples.

It's nothing more than well-fermented bread. The more advanced the bulk fermentation is, the more even the crumb is. On the “lacy” side, the style of bread that Trevor talks about in his book.

One thing about his book that inspired me to write mine, especially after my bad experience with the publisher, is that he had a voice, and he had a freedom to express those thoughts, because he was on his own. But I wanted to to find my authenticity, and to present it that way. Because it is very easy to copy and do something that is already been done. I just took that as inspiration to develop at my own way, and to create my own authenticity, because authenticity is important.

AJ: Yeah, I agree. And I think that you succeeded in that.

Thank you. I try every day. And if it wasn't for all these lovely, loyal people that follow me every day that I help freely. I answer a lot of questions daily, and I don't mind. It's just very rewarding.

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.