Stiffed

On stiff vs. liquid levains

Table of Contents

A starter can be stiff or liquid, depending upon the amount of water relative to flour present. There is no hard and fast line between stiff and liquid starters, but generally speaking, stiff starters contain more flour than water, ranging from 50% up to about 80%, while liquid starters contain equal parts flour and water (100%), or more water than flour (up to around 125%). (As for what you call starters between 80 and 100%, your guess is as good as mine.) Keep in mind that everything depends upon the thirstiness of the flour in question: A levain that is liquid using white bread flour will be stiff(er) when made using a whole-grain flour at the same ratio. In order to create a whole grain starter of the same consistency, more water will be needed.

Liquid starters, despite being the favored style for the vast majority of bakers today (especially home and cottage bakers), are actually a relatively recent invention. They were first created by French bakers Patrick Castagna and Éric Kayser in the early 1990s, when they were looking to mimic the flavor and dough properties of a yeasted poolish in breads, but using sourdough. Before this, nearly all bakers maintained their starters at “stiff” levels of hydration. Since then, an entire industry has arisen to allow larger-scale bakers to ferment, hold, and distribute liquid levain to mixers (this process is only possible with a liquid levain, since their loose consistency allows them to be moved around the bakery through pipes). In all my years of hanging out in bakeries, I’ve never met a baker who used one.

My friend James MacGuire, one of the smartest and most knowledgeable bakers I know, is not a fan of liquid levains. He considers their advent to have marked the end of an era in sourdough baking, after which the quality of the breads declined rapidly. (He wrote an article about the history and drawbacks to the use of liquid levain in the BBGA’s Summer 2015 issue of Bread Lines.) James has traveled widely, particularly in Europe, where levain bioreactors are most commonly used, so I defer to his expertise when it comes to the quality of the breads made in these bakeries. My take is that the loss in quality that James attributes to the move from stiff to liquid levains has less to do with the shift itself than with a general decline in the care with which bakers using liquid levain give their starters. This is likely compounded in bakeries using automated bioreactors to maintain their levains, since the mechanization could easily encourage a less thoughtful approach.

But I think these issues vanish when fermenting liquid starters on a more modest scale, using traditional techniques and equipment, and a careful approach to fermentation. I'm all for letting a baker choose one style of starter over another for any reason, but, unlike James, I think excellent bread can be made with both stiff and liquid levains.

The pros and cons of using stiff starters

- All else being equal, stiff starters favor acetic acid over lactic acid production. Acetic acid is a volatile and more tart-tasting acid, which means that the use of a stiff starter can be used to produce breads with a noticeably more sour flavor profile and a punchy aroma. But this effect is relatively mild in isolation. (In other words, it’s just one of many factors that influence the balance between acetic and lactic acid production; flour type, temperature, and seed amount also come into play here.)

- More importantly, stiff starters also favor yeast growth over bacterial growth, which means breads made with a stiff starter (particularly one maintained regularly that way) should be milder in flavor/tang than ones made with a liquid one. They can also gain greater lift and/or proof more quickly/reliably, since their yeast populations can be so much more robust.

- Stiff starters are also slower to ferment and more stable than liquid ones (since they are slower to degrade), which means they can be held at “mature” levels of activity longer, even at room temperature.

- They are also more stable when refrigerated, which means they make a good choice if you are planning to store your starter for a long time in the fridge before refreshing it again, or if you want to keep it in tip-top shape, despite cold-storing it between uses.

- Stiff starters have lower enzymatic activity relative to liquid ones. As a result, they are less useful for promoting extensibility in a dough. (Or are the better option when trying to avoid an overly extensible dough.)

- On the other hand, stiff starters are, well, stiff, which makes them harder to mix than liquid starters, since they require kneading instead of stirring to form a uniform dough.

- They are also more work to incorporate into the final dough, especially when mixing by hand.

- Unlike with an equal-parts water and flour 100%-hydration starter, the math involved in formulas with stiff starters can make things bit more complicated. (It’s easy to make calculations on the fly when a starter is equal parts flour and water, not so much when you need a specific amount of levain with different amounts of each.)

The pros and cons of using liquid starters

- All else being equal, liquid starters favor lactic acid over acetic acid production. Lactic acid is not volatile, and has a more subtle acidity than acetic, so breads made with liquid starters are often milder than those made using stiff ones.

- But, again, this effect is mild in isolation. More importantly, bacterial growth is promoted in liquid environments, so a bread made with a liquid culture (particularly one maintained regularly at that hydration) is more likely to provide a sour flavor profile than one made from a stiff levain.

- Liquid starters are easy to create, because the math is simple and they can be stirred together with a spoon or dough whisk in seconds, without kneading.

- Liquid starters are easy to incorporate into a dough, whether by hand or machine.

- Liquid starters are loose enough to be quickly and easily stirred mid-fermentation, in order to oxygenate them for a boost of activity. (This is something I plan to discuss here soon, but you are welcome to give it a try yourself in the meantime!)

- Liquid starters have higher enzymatic activity than stiff ones, which means they can confer greater extensibility to a dough. This makes them the better choice for breads that require extensive manipulation during shaping, like baguettes, bagels, or pizza.

- Liquid starters are quicker to ferment than stiff ones. (The rate of fermentation in a starter can always be controlled by varying the amount of seed used, so this isn’t necessarily a negative.)

- On the other hand, liquid starters are also quicker to degrade compared to stiff ones, making their window of use narrower.

- They are also less stable under cold storage, requiring more frequent refreshments to keep happy.

So which should you use?

For years now, I have advocated the use of a liquid levain made using white flour, maintained at 100% hydration. I’ve been using it myself all this time, and it’s worked great, so I still stand by it. Liquid starters work reliably, are easy to measure and mix, and the flavor profile they produce (at least using the methods I do) is excellent and mild enough to convert even those who don’t like “sour” sourdough breads into fans. And any of James’ objections to the use of liquid levains are either irrelevant or easily avoided in a small-scale baking context when using a careful approach to levain fermentation.

Also, it’s important to remember that many liquid levains are maintained at 125% hydration, which is 25% higher in hydration than those held at 100%. So in a sense, 100%-hydration starters already represent a compromise between the two extremes. Given how many bakers work with 100%-hydration starters successfully, it’s possible this approach represents the best of all worlds in terms of ease-of-use and effects.

If you are a beginning sourdough baker, or are happy with the breads that a 100%-hydration levain provides, there’s no reason to use anything else.

But I can confirm that starters maintained at a stiff hydration levels can definitely boost yeast activity over that of bacteria, so there’s also no reason not to try it out yourself and see what you think. Moreover, I think anyone looking to keep their starter as healthy and happy as possible might want to use a lower hydration when storing it in the fridge between uses, because it is bound to be more stable that way. (Again, we know that 100%-hydration levains do just fine in the fridge, but lowering the hydration should allow it to become and stay even happier, especially when held for longer durations between refreshments.)

It’s important to keep in mind that starter will likely take several refreshments to adjust to its new environment, so you should give it awhile before you evaluate the effects of the new hydration. That said, I have baked breads successfully using a stiff levain made from a liquid one after a single refreshment, and vice versa.

One simple approach for those who want to maintain a stiff levain for storage but still continue to sometimes use liquid levains for baking is to do a single build at 100%-hydration just before mixing a dough. (This is what I’m doing right now, and it seems to work fine.)

What hydration stiff starter should you use?

The stiffer the better, in terms of its effect on the dough, but really stiff ones (between 50 and about 65% hydration) are annoyingly hard to mix, in my opinion, at least by hand. (Using a mixer or food processor is always an option, if you don’t mind the extra dishes.) A nice compromise is 75% hydration, which is far easier to knead together quickly, even by hand. It’s also reasonably straightforward, math-wise. (This is James’ preferred hydration, by the way.)

Converting liquid starters to stiff ones (and back), two ways

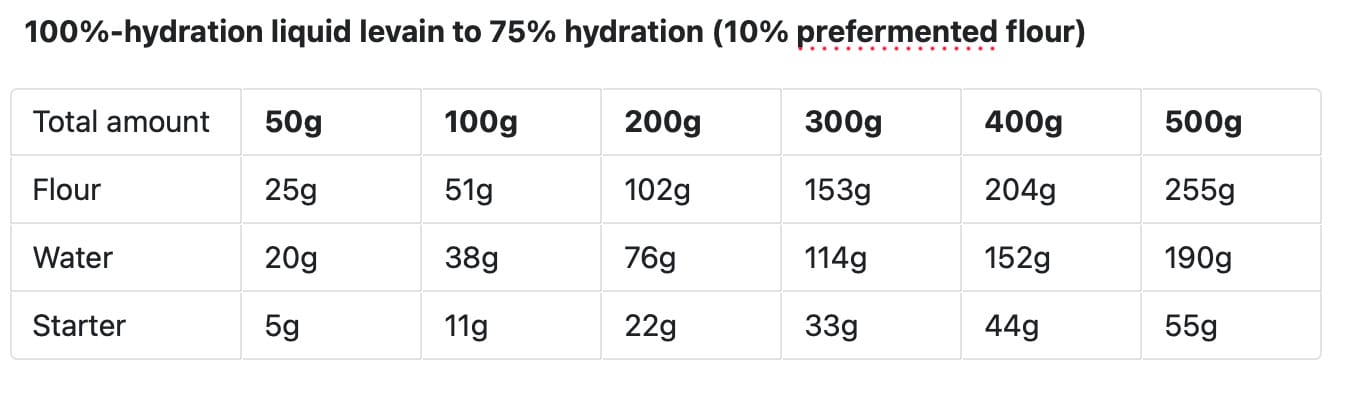

The simplest way to convert from one hydration of starter to another is to use a formula, like these ones I created for you1, one to go from 100% hydration to 75% hydration:

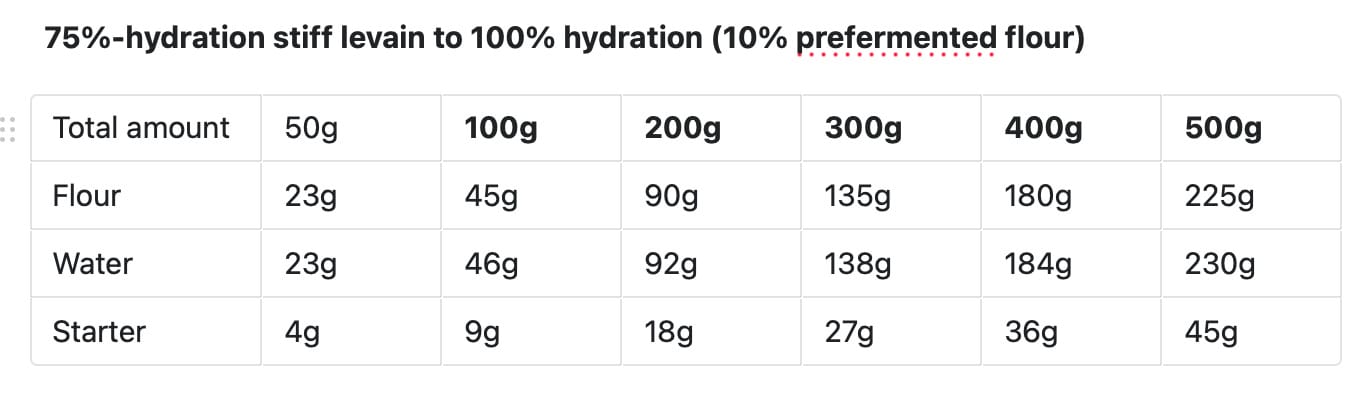

And one to go the other way:

Each of these, with 10% prefermented flour, should give a culture that matures after about 12 hours at room temperature. Once you have the culture, you can refresh it at whatever seed amount you like. (Using 25% prefermented flour instead should give a culture that is mature in 4-6 hours. See below for cheatsheets for several 75% hydration starter maintenance formulas.)

Another way to convert one hydration of starter to another is to “fudge” it by using a small amount of seed, added directly to a mixture of flour and water that is at the exact final desired hydration. In other words, if you need 300g of 75% hydration levain, just combine 170g2 flour, 130g3 water, and a small amount of 100%-hydration levain (say 20g), and let it proof. The difference between the actual hydration (77.7%4, in this case) and the desired one (75%) is insignificant enough to ignore, especially after a few more rounds of refreshment at the same hydration. Going from stiff to liquid is even simpler: Just mix up equal parts flour and water and add a small amount of stiff starter. Again, the final hydration will be close enough to work.

Maintaining a 75% Hydration Starter

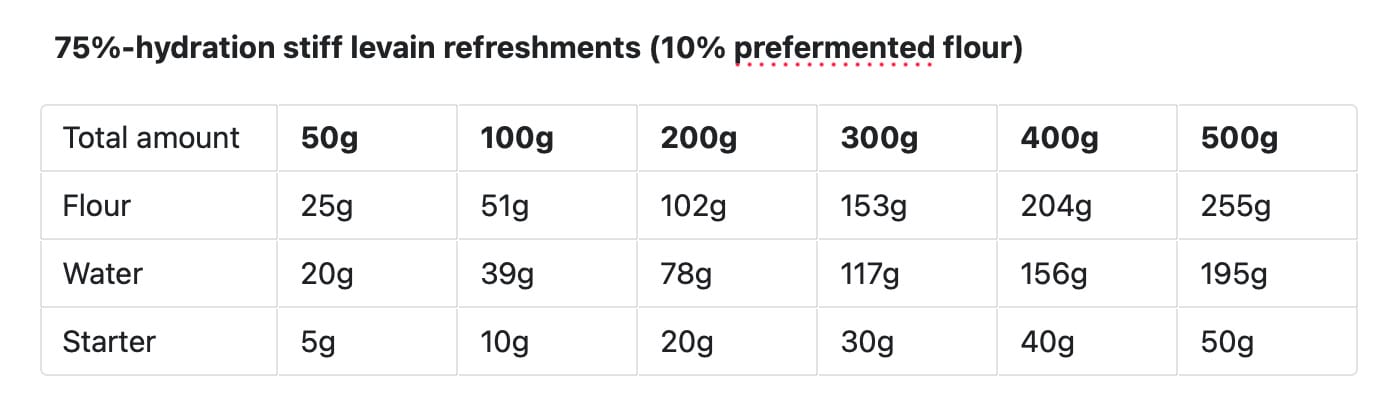

As I mentioned several times above, it’s a comparatively annoying to calculate the amounts needed to mix up a stiff starter, so it’s helpful to have a “recipe” handy. Here’s a cheatsheet for building amounts of 75% hydration starter from 50 to 500g, containing 10% prefermented flour (~12h to maturity):

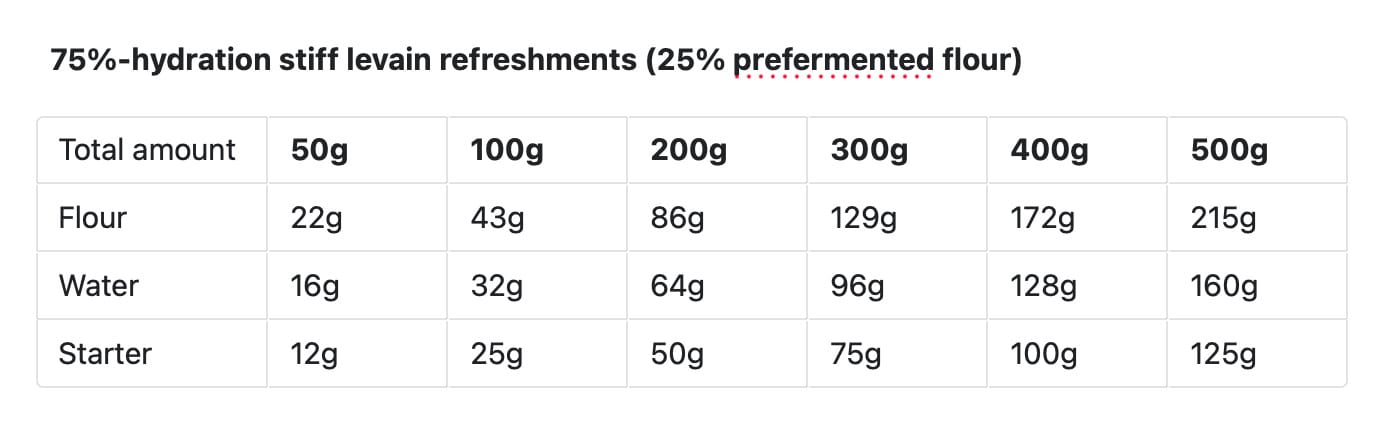

And here’s one containing 25% prefermented flour (~6h to maturity):

Phew, that was a lot! (And I didn’t even go into the other way people classify starter types, which is a story for another day.) Hit me up with questions if you have them.

—Andrew

This math is SO annoying here that I made and remade these charts too many times to count, after having flubbed the calculations repeatedly. I THINK they are correct now, but am not 100% certain. I hope someone here will check my math and let me know if they are off. (And yes, they are rounded slightly to avoid fractions of a gram. Close enough for government work, as they say.) ↩

300 ÷ 1.75 ↩

300 - 170 ↩

140 ÷ 180 ↩

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.