Sourdough Strategies

A streamlined approach to levains for home bakers

Table of Contents

Over the years I have tested a wide variety of approaches to levain-building for sourdough breads. Most of them have worked well, but I think I have finally landed on a universal set of methods that both works reliably (for me) and builds some flexibility into the process. This is something that is especially important for home bakers, who—unlike pros—aren’t working with bread all day (or all night) long.

Most of us have to sleep some of the time—usually between the hours of 10pm and 7am. This leaves essentially two times during the day you’d want a levain to ready for use in a dough—early in the day or in the afternoon. Here’s why:

For a same-day, all-ambient proofed dough (i.e., one that doesn’t get retarded), you ideally want to start the final dough early in the day, so that it is ready to bake by the afternoon or early evening.

On the other hand, if you are retarding the dough overnight, then you probably want the dough ready to shape by the evening. I don’t like to retard most of my breads much longer than 12 hours, since I find they lose volume when I do, so I aim to shape them by 7pm or so. That way I can bake them first thing in the morning, 12 to 15 hours later.

Given those parameters, there are three basic approaches I turn to: an overnight mature levain, a two-stage mature levain, or, occasionally, a two-stage young levain. (I won’t talk about the amount of prefermented flour in the levains here, since I’ve found these methods work regardless.)

The overnight mature (stiff) levain

In order to have a levain that is ready for use first thing in the morning, I will build it the evening before. I’ll use either white or whole-grain flour (whole-wheat or whole-rye). The choice of flour matters less here, though if the final dough contains a whole-grain flour, I’ll usually use it in the levain too.

I’ll typically build this as a stiff levain, at 70% hydration for white flour, or 75% for whole-grain flours. (Other bakers like to build their stiff levains at much lower hydrations—50% or so—but I have found 70-75% to work just as well, while still leaving the levain easy-to-mix.)

The reason I do so is to restrain enzymatic activity, to prevent the levain from overproofing before I get to it, and to give me a little more flexibility with when I can use it. Liquid levains mature and degrade quite quickly; reducing the hydration slows them down, giving a wider window of use once mature. I’ve found that a stiff levain has an extra 2 to 4 hours of stability, which means I don’t have to stress about getting to it right away in the morning.

I’ll use cool water in the levain (~70˚F/21˚C) and proof it at cool room temperature (also ~70˚F/21˚C). And I’ll typically use 2–5% starter as the seed, less in the summer and more in the winter. I will usually try to push the fermentation of this levain as far as possible, so it has maximal proofing power. When it is ready to go, it will have about doubled in volume and will have leveled off (but not collapsed).

Obviously, because the levain is of a low hydration, I’ll make sure to adjust the hydration of the final dough to make up for whatever is missing (assuming that the formula normally calls for a 100%-hydration liquid levain).

The two-stage mature (liquid) levain

If instead I need a levain ready in the middle of the day, I will build it in two stages, with the same amount of flour in each stage. And if I happen to need a liquid levain for some reason (to promote extensibility in the final dough, most of the time), then I’ll use this approach too.

Here’s what I mean: Say a formula calls for 200g of liquid levain—containing 100g flour and 100g water. The night before I need it, I’ll mix a stiff levain like before, but with half the total flour—50g—along with 38g water (75% hydration), and ~2g starter; I’ll usually mix this in a jar large enough to hold all of the final levain, so I don’t need to use multiple containers.

The next morning I’ll add 50g flour and 62g hot (~105˚F/40˚C) water to the jar, which will bring its hydration to 100% and its temperature up to about 85˚F. I’ll then proof it at 82–85˚F for about four hours, by which time it should be about tripled in volume and ready to use. (It’ll remain stable for use for another hour or so, but if I cannot use it right away, I’ll move it to a cooler spot to slow it down until I can, just to keep it from overproofing.) Proofing warm and building it into a liquid levain will ensure that it moves quickly, so it will be ready for use when I need it.

There’s one way I change things up with this approach: If the final dough is going to be retarded (as many are), I will avoid using rye flour in any stage of the levain. This is because rye is much more enzymatically-active than wheat, and that can mean loss of volume while the loaves sit in the fridge, since protease enzymes will chew up the gluten and amylases will continue to degrade the starches.

[Edit 2/7/25: Since there have been some questions about rye, levains, and retarding, I wanted to add a little more. This does not mean you cannot use rye in your final doughs if you are retarding them (I do it all the time). The idea is that you want to minimize it where possible, by not using it in the levain.]

The one bonus of this approach is that I can make a relatively small levain the night before I might want to bake; if for some reason I don’t end up making a loaf the next day, I won’t have wasted much flour.

The two-stage young (liquid) levain

Occasionally I will use a young levain, meaning one that has a lot of yeast in it, but a relatively low amount of lactic acid bacteria. This will boost yeast activity in the final dough and minimize sourness. (This is standard practice for the Tartine school of bakers like Chad Robertson and Richard Hart.)

The way I’ll do it is identical to the two-stage mature levain, except I will use it after 1-1/2 to 2 hours of proofing, when it will be about doubled in volume. Here’s how it works:

The yeast in a newly-mixed levain begin to consume the sugars in the flour and divide pretty much right away. Meanwhile, the lactic acid bacteria are slow to get going, taking an hour or two under typical conditions to adjust to their new environment and begin dividing. (Many bakers refer to this as their “lag phase,” meaning the time in which they lag behind the yeast.) As long as the levain is allowed to mature, they’ll make up for lost time with a greater rate of activity, and the density of yeast and bacteria will be maximal when it is ready for use. But if you jump the gun and use the levain early (young), the bacteria will barely have woken up, and there will be a greater density of yeast than lactic acid bacteria.

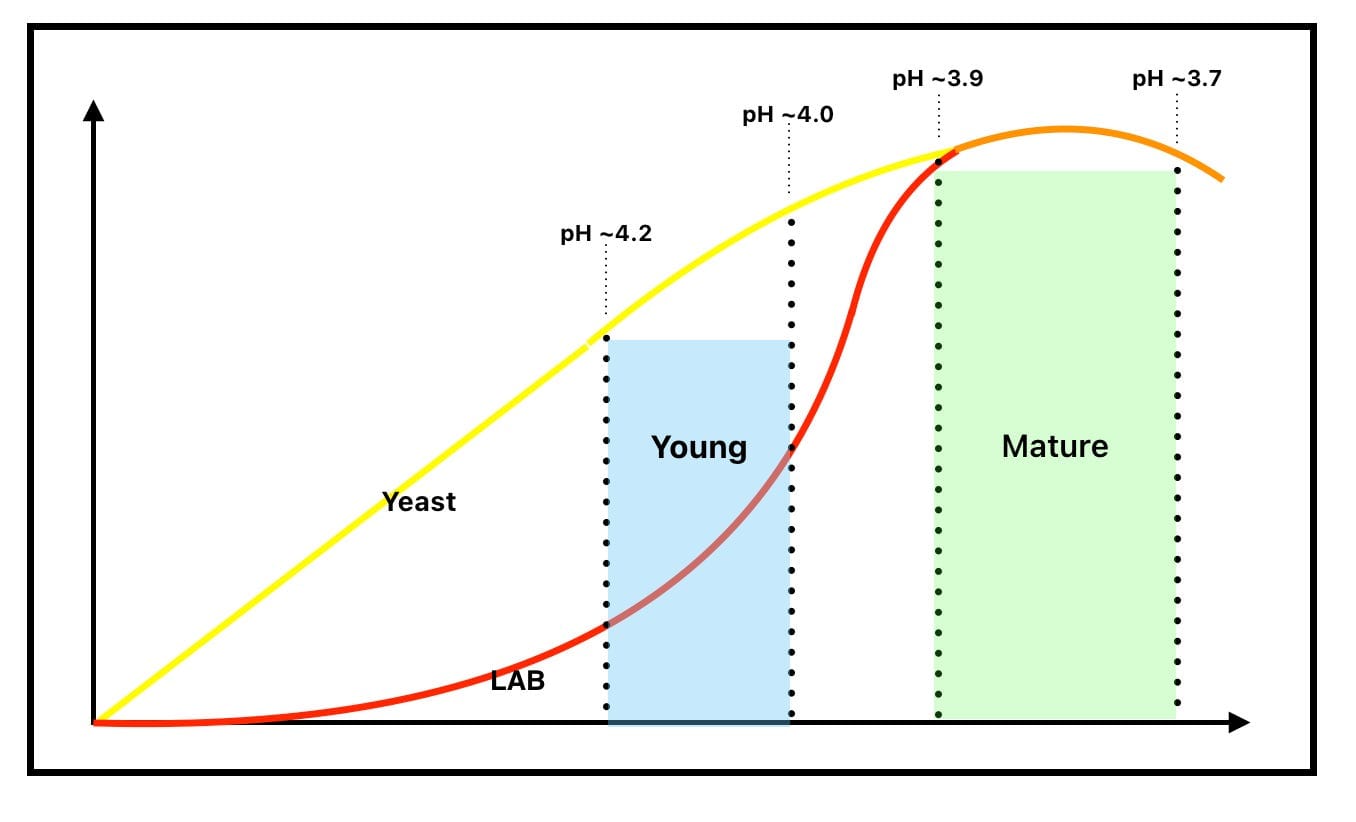

The most important thing to understand about young levains is that there will still be a lower density of yeast in a young levain than in a mature one. The yeast may be much farther along than the LAB at that point, but there would still be many more of them if you were to let the levain mature. (See the graph above, which should make it clear.)

As a result, if you want the final dough to proof at a similar rate as it would with a mature levain, you need to use more of it. I have found that I want to use about 30% more prefermented flour in my final doughs to get a young levain to behave like a mature one. (For example, if a dough normally calls for 15% prefermented flour with a mature levain, I’ll typically increase it to 20% for a young one.)

Young levains & the sweet starter process

Incidentally, the young levain process is identical to that used to prepare a levain for use in Ian Lowe’s sweet starter; the only difference (aside from the requirement that you use white flour in all stages and a slightly lower proof temperature) is that you need to repeat the second (liquid/young) stage one or more times to really depress the bacterial activity in it. (If you do three quick liquid builds, which is ideal, you’ll get a young young young levain, with virtually no bacteria present in it.)

pH and levain maturity

I really don’t think most bakers need to use a pH meter or even consider pH for success; I have a pH meter, but I rarely use it myself. But since I do have one, I did pull it out to confirm my approaches here are sound.

It’s common wisdom that a mature levain will have a pH between 3.9 and 3.7. Above 3.9 it will be slightly immature, and below 3.7 it will be on the road to overproofing. Meanwhile, a young levain should have a pH of between 4.2 and 4 (meaning it is less acidic than a mature one, thanks to its reduced LAB activity).

When I tested my overnight and two-stage mature levains, they had a pH of 3.8, which is right in the middle of where I’d want them to be. And my young levain was at pH 4.1 after 90 minutes, also within the ideal range.

What are your thoughts on this set of approaches? Do you feel like they’d cover all of your own needs for sourdough scheduling?

—Andrew

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.