Ruby Tandoh's 'Cook as You Are'

A book excerpt & a recipe

Table of Contents

I loved this recent Vittles piece by Ruby Tandoh on the fascinating history of Sainsbury’s design studio and how it defined the look and feel of supermarket-brand food in post-war UK:

Tandoh is a regular contributor to Vittles and The New Yorker, and her writing is something I always make time to read. (Be sure to check out her recent NYer story on The Hard-Won Pleasures of a Yeasted Cake, something I need to revisit as I work on my book, as the line between yeasted loaf and yeasted cake is one I want to define more clearly.)

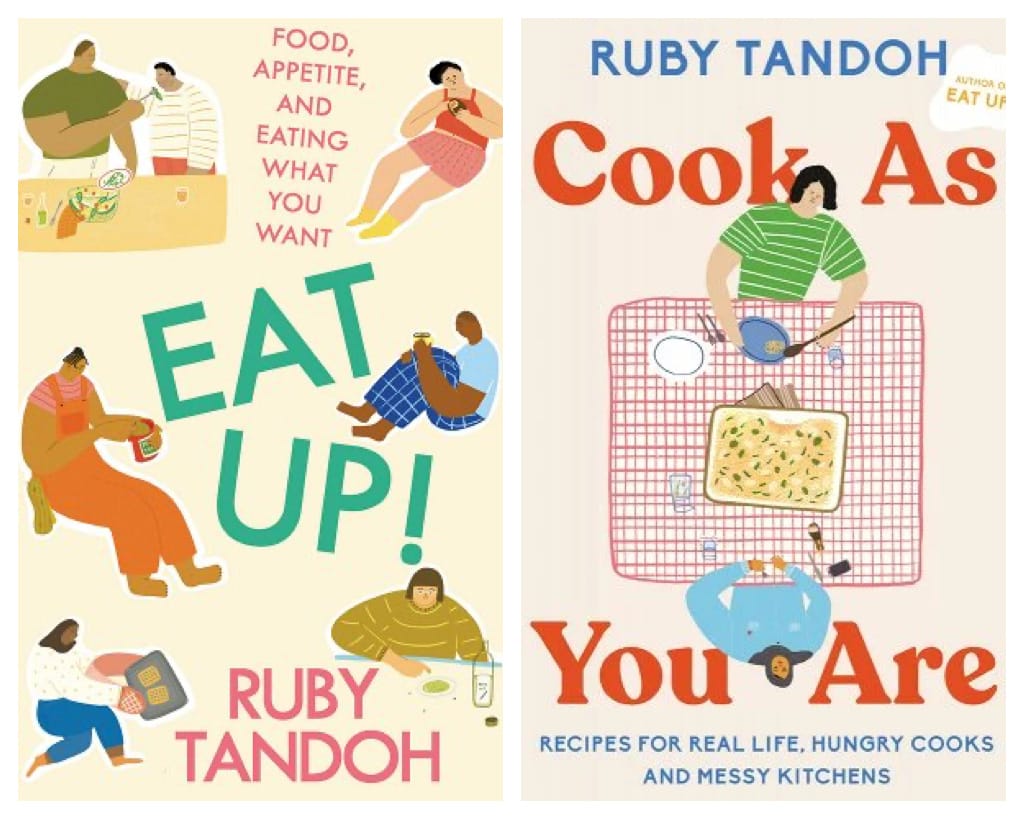

Tandoh published two books last year: Eat Up!: Food, Appetite and Eating What You Want, all about food, pleasure, and body image (which I haven’t read yet, but have), and Cook as You Are: Recipes for Real Life, Hungry Cooks, and Messy Kitchens, which I love. In fact, I love it so much that I cited it as one of my influences in my own book proposal. It’s one of the handful of books I keep in mind as I work on my own, for numerous reasons.

One, it embraces the fact that each cook is an individual with a unique set of skills, resources, and experiences, which favors encouragement and reassurance over prescription, gently guiding the reader toward making choices that fit where they are right now, rather than insisting they do something in a particular way. Two, it wears its influences on its sleeves: Rather than pretending that its recipes arrived unbidden from Tandoh’s own culinary genius, it references other cooks and cookbooks freely and generously, even going so far as to put a list of relevant citations at the front of each chapter, rather than the end, or at the back of the book, never to be seen. Finally, it reminds the reader that cooking and eating can and should be about joy, whenever possible, and that finding pleasure in the kitchen is the surest way to create a cook for life.

Here’s part of how Tandoh describes the book herself:

A lot of the time, cooking is just functional: we cook to live, not the other way round. But if you’re reading this book, I’m guessing that there are at least moments in your life when food rises beyond mere sustenance, when you want to enjoy yourself as you cook and eat. And there is so much to be enjoyed. There is noticing an appetite—for fries, or hot chocolate, or soothing pea soup—at the exact moment it awakens, and knowing that you have the resources and the ability to satisfy that craving. There is the pride you have when you can feed yourself or someone you love. There is the freedom to cook by numbers or to take creative license, to respect or disrespect the recipe in front of you. There is the multisensory fantasia that home cooking can become, when you draw on every one of your senses to guide you towards a good meal. And—most important of all—at the center of all of this there is you: in your ordinary kitchen, with your likes and dislikes, your tastes and aversions and your washing-up piled in the sink, cooking as you are.

As I said, I love this book, which is why I’m so happy to get to share a little of it with you all today. Below, I’ve got the introduction to the section that covers bread recipes, along with Ruby’s recipe for Rosemary Baby Buns.

—Andrew

How bread works, by Ruby Tandoh, from Cook as You Are

If you’ve never made bread before, it can help to know a bit about what it’s made of and how it works. Some breads, such as soda bread, use chemical raising agents (things like baking powder or bicarbonate of soda). Other breads, like flatbreads, are unleavened, which is to say that there’s nothing in the mix to give them any “lift” as they cook. But most of the time when we talk about bread, we are talking about yeasted bread, which gets its “lift” from yeast.

Yeasts are single-celled organisms from the fungus kingdom. When added to malted grains, yeast will ferment, turning sugars into carbon dioxide and alcohol to form the building blocks of beer. In bread, enzymes in the yeast help to break the complex starch molecules into smaller molecules of sugar. These sugars are then fermented by the yeast, changing into alcohol (in very small quantities) and carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide forms tiny bubbles in the dough, causing the dough to expand. When the dough is cooked, these gas bubbles get bigger again, so the bread rises even more in the oven.

Whatever kind of yeasted bread you make—whether it’s a giant French boule or a batch of featherweight doughnuts—the four main ingredients remain the same: flour, water, yeast and salt. (There are some exceptions: in sourdough breads, wild yeasts in the flour and in the air are slowly and carefully nurtured, rather than yeast directly being added to the mix; some breads, such as Italian pane toscano, are made without salt.) Wheat flour contains proteins, including the much-maligned gluten, which develop into a strong, elastic “web” as you knead the dough. This “web” catches those bubbles of carbon dioxide produced by the yeast: you can see evidence of this in a bread’s holey crumb, with little areas of dough surrounding bubbles of air. Water is crucial for hydrating the flour, which allows this gluten network to develop and the yeast to start fermenting. Yeast, as I’ve mentioned, provides lift, but also adds loads of flavor by breaking larger, tasteless molecules into smaller, more flavorful ones like sugars and amino acids. And salt, as well as enhancing flavor, helps to strengthen the gluten network, giving your bread some bounce. Just bear in mind those four cornerstones of breadmaking— flour, water, yeast and salt—and you’ll be well on the way to being a confident bread baker.

In terms of the steps involved in breadmaking, I think the whole thing is best seen as a kind of dance— faster sections, slow parts and moments when you (and the dough) both rest. After you’ve mixed the ingredients, you knead the dough: a vigorous way of building up the dough’s strength and elasticity. After that, you set it aside to rest and rise. Once the dough has risen, you return to it and shape it, gently coaxing it into its final form—whether that’s a baguette or a bun. Then the dough rises some more, changing from compact and elastic to larger, airier and more fragile. At this point, it’s time for it to go in the oven—a sudden ramping up of tempo and energy that will see the bread rapidly expand, cause the yeast to die and transform the soft dough into an airy crumb. If you want to learn more about bread, I’d really recommend James Morton’s Brilliant Bread, New World Sourdough by Bryan Ford and the classic The Bread Book by Linda Collister.

ROSEMARY BABY BUNS

CAYA Tandoh Rosemary Baby Buns4.54MB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownload

My friend came back from Mexico last year with two little buns wrapped inside a sandwich bag, inside a plastic bag, tucked into a corner of her backpack. From Panadería Rosetta in Mexico City, the buns were flavored with rosemary and sugar with sticky, salty, caramelized edges. My friend, knowing me as well as she does, knew I’d lose my head for these bollos de romero—rosemary buns—and so smuggled them a full 5,500 miles back to dreary England for me to try. Everyone should have a friend like this.

Luckily, you don’t have to wait until someone happens to be coming back from Mexico City with room in their carry-on luggage: you can very easily make a version of these buns at home. The ones I tasted were made with lard mixed with the sugar and rosemary, which gave them a perfect semi-savory richness. If you want to replicate this exactly, check out the variations and substitutions section at the end of the recipe. But it’s my guess that most of us are more likely to have a block of butter than of lard in the fridge, so with convenience and vegetarians in mind I have developed a butter-based version for you to try out.

If you can make these tiny “baby” swirls, as soft as a baby’s bottom and sweet with rosemary, you can make any bread.

Makes: 24

Ready in: about 4 hours, but much of this is quiet time while the dough rises, so you can fit life into the gaps. There’s a take-your-time method below in case you want more flexibility.

Make-ahead and storage tips: follows recipe.

For the dough:

4 cups (500g) bread flour, plus extra for dusting

1 teaspoon salt

2 teaspoons (8g package) active dry yeast or ½ ounce (15g) fresh yeast

1⅓ cups (315ml) lukewarm water

For the filling:

½ cup (110g) salted or unsalted butter, softened, plus a little extra to grease the tin

¾ cup (175g) superfine granulated or soft light brown sugar

Pinch of salt, optional

Leaves from 8 fresh rosemary sprigs, finely chopped

Special equipment:

stand mixer with dough hook attachment, optional

- In a large mixing bowl, mix together the flour and salt. In a measuring jug, mix the yeast with the water until dissolved. Make sure the water is barely lukewarm: if it’s too hot, the yeast will die. Pour the yeasted water into the flour and salt mixture, and bring together using a wooden spoon until a shaggy dough forms and there are no more big patches of dry flour. At this point, it’s time to ditch the utensils and get your hands dirty. There’s nothing so effective for kneading dough as a human hand, so unless you have mobility problems or sensory aversions that might make it difficult to hand-knead the dough (in which case you can use a food processor with a dough hook attachment), you should get in there yourself.

- It’s much, much easier to see how to knead dough by watching the process rather than reading about it. There are lots of different techniques, but they all achieve roughly the same thing: stretching, building and reinforcing the gluten network in the dough. With this in mind, it might help you to have a look on YouTube at examples and to find a method that works for you. Here’s a simple method that I use: Tip the rough dough onto a clean work surface. (Don’t worry if the dough’s a bit sticky. Stickier dough means lighter bread, and it’ll become less glue-like the more you knead it.) Holding the nearest edge of the dough under the heel of one hand, stretch the far side out under the heel of your other hand, dragging the dough out into an oblong or oval shape along the surface. Then fold the far end back over to meet the near end, so the dough is folded in half. Give the dough a quarter turn, so another side is now nearest to you. Repeat: stretching, folding and then turning the dough again and again for 5–8 minutes, or until the dough is elastic and smoother, rather than shaggy, torn and very dimpled. (Realistically, you can’t over-knead it if you’re kneading by hand—no matter your optimistic googling of “can you over-knead dough” around the 2-minute mark. Just be patient, put a podcast on and let the dough come alive in your hands.)

- Wash out your mixing bowl and dry it, then return the kneaded dough to it. Cover with a plate, plastic wrap or a damp tea towel. Leave to rest and rise at room temperature—around 65– 75°F (18– 24°C). If your house is slightly warmer or cooler than this, don’t worry! Just remember that you’re working with a living organism— yeast—and this organism works faster when it’s slightly warmer, and slower when it’s cold. At very cold temperatures, around freezing point or below, the yeast will stop working altogether. The dough is ready when it has almost doubled in size, which should take anywhere between 1 and 2 hours depending on the ambient temperature.

- While the dough rises, mix the butter and sugar to a paste. If you’re using unsalted butter, add a pinch of salt.

- Once the dough is risen and ready, tip it out from its bowl onto a work surface lightly dusted with flour. Use your hands to tease the dough into a rectangle shape around ¾ inch (2cm) thick. Dust the top of the dough rectangle with a little flour. Now take a large rolling pin and roll the dough out to a very large, long rectangle, around 12 inches (30cm) long and 27–31 inches (70–80cm) wide. (If your kitchen space is limited, you might want to divide the dough in half and create two 12 x 16 inch/30 x 40cm rectangles instead of the one large one.) It might spring back as you roll it out, but if you’re patient with it you’ll eventually manage to coax it to the right size.

- Using a small knife or spatula, thinly spread the butter and sugar mixture all over the dough. Sprinkle over the chopped rosemary leaves. Now, starting at the very long bottom edge of the dough rectangle, roll it away from you like a Swiss roll. You should end up with a very long, slim log of swirled dough. Cut this log into 24 slices (each 1–1¼ inches/2.5–3cm wide)—you’ll be able to see the pale spiral streak of butter and specks of rosemary.

- Grease a large roasting pan—roughly 13 x 9 inches (22 x 33cm)—with plenty of butter (the size matters here, because you want the buns to be close enough that they begin to touch as they rise and bake). Arrange the buns in the pan, cut side up so that you can see the swirls, like a tray of cinnamon buns. Leave to rise, uncovered, for about an hour—or until they’re about 1½ times their original size and noticeably puffy and soft. While they rise, preheat the oven to 425°F (220°C).

- Once the buns are risen, bake them in the preheated oven for 15–18 minutes, until they’re well-risen, their tops are beginning to brown and crisp and the butter is sizzling up through the swirls. Leave to cool for just a few minutes, then transfer out of the pan and to a wire rack while they’re still warm—otherwise, the caramelized sugar might stick them to the pan. These buns are best served warm.

Storing

Store in an airtight container in a cool, dry place for a couple of days, but I’d recommend giving them a few minutes in the oven to refresh them before you eat. They can be frozen too: separate the buns, then store in sealed freezer bags for up to 1 month. Defrost overnight at room temperature and warm in the oven to serve.

The take-your-time method:

If you’ve got a busy day ahead, you can mix and knead the dough in the morning, using cold rather than lukewarm water. Put the dough in a bowl, cover the bowl tightly with plastic wrap (the dough will dry out otherwise) and place in the fridge until the evening. That evening, take the dough out of the fridge, shape into buns and leave to rise at room temperature for 3–4 hours, or until roughly 1½ times their original size. Bake as above. If you prefer to bake these in the morning, make the dough the evening before, leave to rise in the fridge overnight, then shape first thing in the morning and let rise at room temperature for 3–4 hours.

Variations and substitutions:

To make a version with lard instead of the butter, just like they make at Panadería Rosetta, swap the ½ cup (110g) butter in the filling for 3 ounces (80g) or ⅓ cup plus 1 tablespoon lard. To make a vegan version, swap the butter for 3 ounces (80g) or ⅓ cup plus 1 tablespoon coconut oil and a good pinch of salt.

I wouldn’t recommend swapping the rosemary for any other herb: rosemary is intensely aromatic, woody and strong as a flavor, and it’s not really something that any other herb could approximate. But feel welcome to use the dough and technique as a starting point for making cinnamon buns (swap the rosemary for 2 teaspoons ground cinnamon), cardamom-scented swirls (swap the herb for the ground seeds of 10 cardamom pods) or even a zesty orange variation (replacing the rosemary with the finely grated zest of 3 oranges).

If you want to give these some gloss, you can add an orange glaze—1⅓ cups (150g) confectioners’ sugar mixed with orange juice until it’s the consistency of thick heavy cream—brushed over the tops of the buns while they’re still warm.

From COOK AS YOU ARE by Ruby Tandoh. Copyright © 2022 by Ruby Tandoh. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.