Rose Wilde

Invites us to taste

Table of Contents

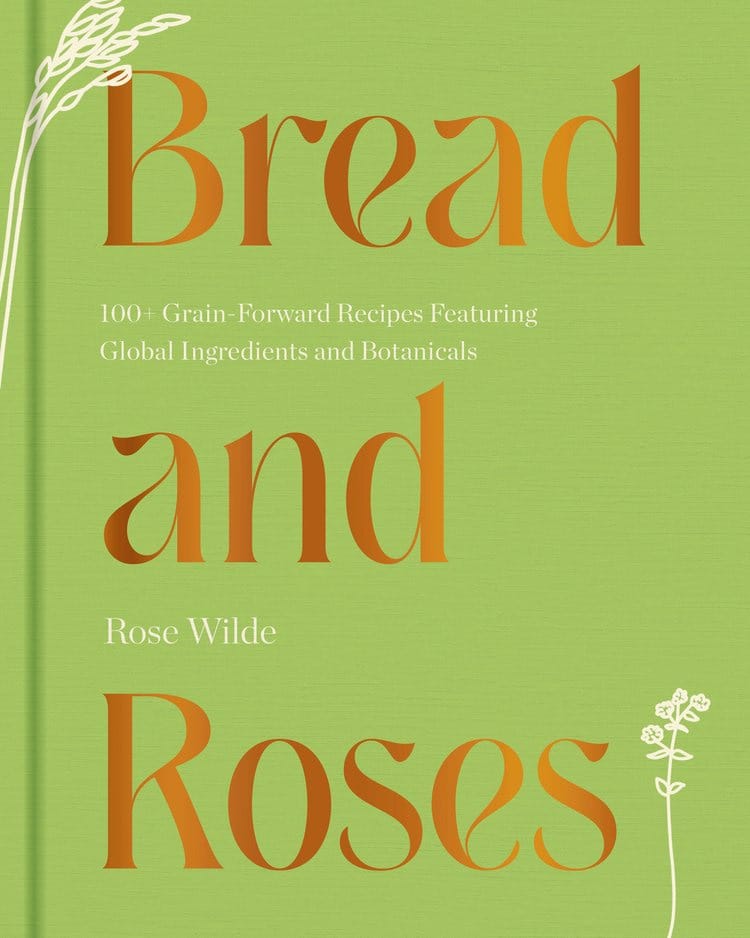

Rose Wilde grew up in Ecuador, and initially trained to be, and worked as an actor. Her next career addressed human rights issues, and she opened a microbakery in 2011, delivering baked goods by bike in Los Angeles. Red Bread grew into a stand at the Santa Monica Farmers’ Market, and eventually a restaurant. She carried her human rights impulses into the workplace, creating an environment that put workers and collaboration front and center. She’s a master gardener and a master food preserver and has brought her kaleidoscopic vision for baking to a series of LA restaurants. Rose’s exuberant cakes feature whole grains, flowers and other botanicals, and her book Bread and Roses invites readers into their own learning and relationship with ingredients and methods.

I (Amy Halloran, hello dear Wordloafers!) met Rose when I was researching my book, and fell immediately in love with her enthusiasm. This conversation is a catch-up between two baking friends who haven’t talked in too long, and a precursor to Rose’s class with the Maine Grain Alliance online, on February 11th, 1-3 p.m. EST.

AH: Your cookbook makes me curious about your teaching journey.

RW: I feel like I've always been teaching. The minute I learned how to do something I wanted to share it with someone. I find learning so exciting. I was very driven in terms of learning, and then I wanted to share it with people. So that was always a part of who I was. I had many summer jobs working as an arts and crafts teacher to toddlers and elementary school kids. Once I got into food, I was so enthusiastic about it and I thought there were so many cool things about it. I mostly taught myself and since I have such reverence for teachers, I sought one. I went to the Gourmandise School in Santa Monica, run by a wonderful woman named Clemence Gossett. In preparation for taking her croissant class, I made croissants 14 times so that I would have educated questions. By the end of the class, she asked do you want to teach here? And so I very quickly started teaching and I wanted to make it as accessible as possible. I wanted people to be as excited as I was, and I wanted to talk about the things that I knew.

Since I come from a background with parents who were very holistic in their approach to food and ran a garden and a restaurant and an apothecary, I’ve been farm to table and whole grains my whole life, and that became the majority of what I wanted to teach people. Clemence was very open to that. And I started teaching in other venues. Working in my restaurant, teaching cooks and pastry cooks how to replicate things was my job. When I worked at other restaurants, teaching and building teams figured there as well. When the pandemic hit, the only thing I could really do that hadn't been shut down by COVID was to teach online. I rediscovered just what a joy it was to only do that, to just be in relationship with people who are interested in learning and making it for themselves, instead of trying to focus it so much on like replication and production. I had wanted to write a book for a long time, but certainly that experience solidified it because the satisfaction I got from teaching was larger than the high of sending out a beautiful slice of something in a restaurant and having people be like, Oh my God, what sorcery? How did you do? Giving someone a recipe and having them do it on their own time in their own sacred space and create their own magic – that’s my favorite thing. It was so amazing and so I refocused my energy to make this book. The book is a way to teach a larger audience and give something that you could come back to on your time.

AH: How did you begin to get so compelled by flavor and variety and getting people to understand the nuances and possibilities of flavor?

RW: I've been very lucky to travel a lot of places and be invited into a lot of different people’s kitchens. My vocabulary just got bigger in terms of what flavors were possible. I often make this analogy whenever people say, I can't do X, I'm like sure you can. The only difference is you don't speak that language right now, but if you committed so many hours to it, you would be able to speak that language and then suddenly you would have a fluency. The only reason I can do this with flavor is because I've been speaking this language for a long time. And I think that in our country, a lot of our vocabulary, especially when it comes to baked goods, is very much like berries, vanilla, chocolate, nuts, caramel and that kind of sums it all up. All of those things are amazing, but there's also all these other amazing things. And you know if variety is the spice of life, then that's all I'm trying to do is just add more spice to your life.

I advocate a diet of eating more. I don't mean in quantity. Eating is often put in negative or fearful terms. Don't eat that, and this is good, and that's bad. I can't buy into that any longer. I think that everything is good, and everything is delicious. Have some adventures. Try some new things. See if you can't add to your own personal canon. I think that's where my love for different flavors came from, was exposure, and from a deep sense of greed. And wanting more.

Having a restaurant and working in kitchens here in Los Angeles, and also staging around the nation and abroad allowed me to play with other people’s lenses of flavor. And I also think of it in terms of my old my first career, which was as an actor, where you're playing a role. These things may not be what I identify with, but this person is obsessed with X,Y, and Z. Let's try and see what it what it would be if I channeled them, you know?

When I was working for Jeremy Fox, he has such a wonderful way of working with flavors. I think his strongest suit is vegetables and salads, and that's what people know him for. But one of his most famous dishes is like a beets and berry situation. And for one of the summer dinners we did, I thought how fun it would be if I reinterpreted that in a dessert. You don't really see a lot of beets in desserts because they're very earthy and frankly, I don't like them. But I saw the challenge, and challenges are a good way to get deeper exploration, so I ended up coming up with this like beet pavlova. With this swirled moose and a ton of fresh berries, and then these little pâte de fruit of beets on top as well, and he loved it.

This was a win for me, and understanding I could transform ingredients like this was unlocking another superpower. I think that there are many ways to explore flavor beyond your personal history. Just challenge yourself. Just find an ingredient and be like, let me see what I can do with this and that's what keeps being in the kitchen super fun.

Making the book, I wanted to put together some of the things that resonated with me. And I wanted taste to be a big part of it. What if you were to taste spelt and you had the tools and language to investigate flavor? I really wanted to give people the language and support and tests that I do to taste grain without telling them this is the only way, this is the right way, this is the definitive [way]. Because I don't think that's true. I think there's many ways to perfect.

And if I tell you a story about where a grain is from and how it's always been used, you're going to remember that. Because as humans, we're all storytellers. Even if you think you don't tell a story, well, your whole life is a narrative. I really wanted to re-center a lot of these ingredients in the culture they were from, which ultimately became an exercise in decolonizing a lot of ingredients. If you rip them away from their culture and just claim that they're great for you, that does have an element of colonization, you know? Without honoring where it's from, we lose so much. Likewise with the botanical portion of it. I feel like in our country, you know, florals are like reserved for Michelin star restaurants where they float delicately on vegetables. But if you go to Lebanon, people go into the mountains to collect blossoms on a certain week and that gets folded into salads or roasted in with meats – and it's for flavor as well as beauty. I thought I could re-center whole grains and botanicals and get people excited about sustenance and beauty, which is ultimately why I named the book Bread and Roses. I was harkening to the really beautiful protest speech by Rose Schneiderman (after the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911) where she says that, you know, we deserve more life than just to live. We deserve to survive and thrive. We deserve bread and roses.

AH: Tell me about your work in human rights.

RW: I think it's definitely the driving force in how I approach food. It’s a lot of restorative justice work in a way. Aside from how I work with ingredients, my business Red Bread is really committed to social justice work. We give a portion of every sale to the Los Angeles Food Bank. I also teach free classes based in preservation and bread baking, mostly to various shelters and centers around Los Angeles, because that's where I'm based. This Wednesday I'm teaching at the Saint Joseph Center, which is a homeless shelter that has a culinary program helps people coming out of homelessness learn how to cook professionally. So then they can be placed in kitchens because that's something where you'll always have a job.

I could teach tons of different things at this point, but I like to focus on preservation and bread making because I think those are two things that are so foundational. If you build your pantry and you can make bread, then there's so many meals right there. Preservation is one of the like fastest way to make your dollar stretch because you can buy in season, you can buy bulk, and you can do a few simple techniques and have food throughout the year that you know what's in it, that is healthy. It also gives you an advantage so that you can advance quickly in a professional kitchen. But this is stuff that everyone used to know, so I feel like I'm restoring knowledge to people who can really appreciate and who need it.

Even when I was strictly working as a human rights lawyer, I primarily was working on issues that affected women and children. There's no way to work with women without food coming up because they are largely the ones responsible for bringing food into the home. I had worked in a lot of restaurants, but primarily the front of house before opening my own. When I did open my own, the only structures for business I knew from human rights, so how I set up my kitchen was based on human dignity and people having a voice. At the time when I explained this to my professional colleagues, they were like, you're insane! Last year I went to Copenhagen because I had the opportunity to go to the MAD Academy, our first presentation was from a former human rights officer who was like, let's talk about how our kitchen should be organized by human rights. I was, like, 10 years later, I am finally justified.

Here are a few more ways to find more Rose!

- Listen to her speak with KCRW’s Evan Kleinman about cake as salad

- EAT MORE is the title of her newsletter

- Jessie Sheehan interviewed Rose for her baking podcast, She’s My Cherry Pie

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.