Real mature

Table of Contents

The other day I sent out a detailed new version of my Quarantiny Starter method, but I wanted to focus in on one aspect of the process, namely knowing when you are getting somewhere with it.

I’m no fan of the “crumb shot” trope and the macho obsession with achieving an open crumb, as if a loaf riddled with giant holes is preferable to one with a finer crumb, or a primary indicator of a baker’s skill. (My go-to toast topping is peanut butter and Mike’s Hot Honey, which I’d prefer to keep off my hands and keyboard, thank you very much.) Yes, there are some instances where a super-open crumb is preferable—ciabatta, baguettes, some pizzas—but not achieving one is hardly a sign of failure.

That said, there is at least one instance where looking at the internal crumb of a sourdough loaf is useful: judging the maturity of a recently-created starter. Over the many months since the Quarantiny Starter project began, I’ve seen a lot of images of people’s loaves, most of them sent with the hope that I could evaluate the health of the starter that produced them. It took me awhile to sort this out, but I now feel like I have a good eye for the difference between a robust, fully-mature starter and one that isn’t quite there yet.

While it is possible in theory to go from zero-to-zooming in just a few short weeks, it’s my sense now that while a young starter, even one that meets all the common benchmarks of maturity—tripling in volume in less than 12 hours, “float test” floating—can be used to leaven bread successfully, there’s often still some time to go until it’s as strong as it will eventually be. And it’s often this last mile that seems to take the longest to get past.

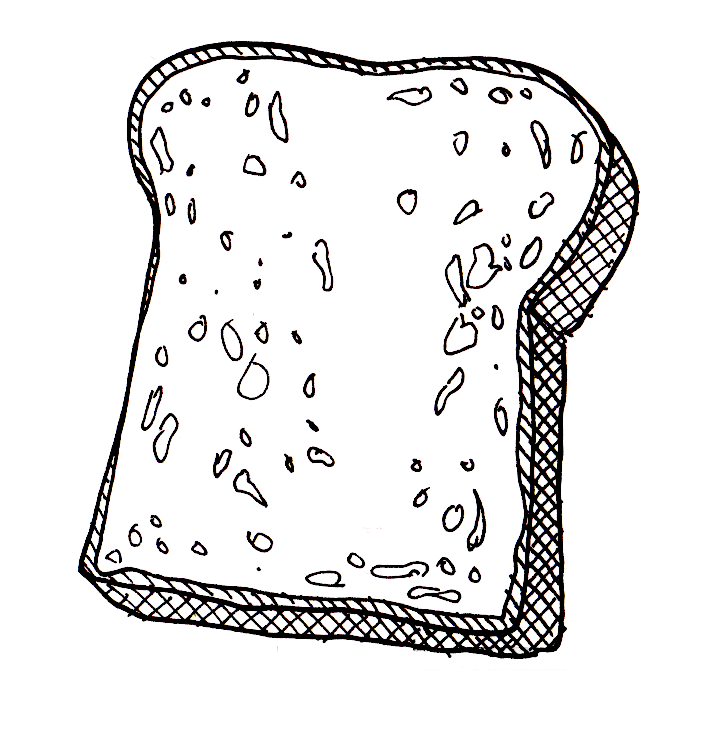

Take this photo, for example, that a friend sent me recently:

The slice is reasonably tall, so it clearly had plenty of oven spring. But notice the crumb, which is made up of a mixture of extremely large, tunnel-like alveoli embedded randomly within a much finer network of bubbles. To me, this is a dead giveaway for a starter that still has time to go before it’s fully mature.

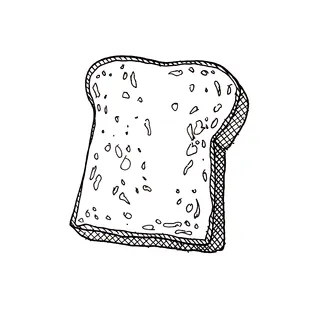

Now compare it to this one, made with a mature starter (mine, in this case, so I know its provenance):

Yes, there are larger alveoli here and there, but they are evenly distributed throughout the crumb, and, more importantly, they are part of a continuum of alveoli of sizes large to small. And they don’t have that tunnel-like appearance that the holes in the former loaf display.

I don’t know yet what causes that effect in a young-but-usable starter, but I suspect it has something to do with the relationship between the chemistry of the starter and the gluten structure of the dough. If I had to guess, I’d say that the alveoli are collapsing during baking and the gases that they contain are combining to form those tunnels, maybe because there isn’t quite enough acidity to provide sufficient strength to the alveoli walls. This suggests either a deficiency in bacterial activity, which isn't something I’d expect to occur in a young starter, given that is is yeast activity that is usually the last thing to ramp up during starter creation.

Or maybe it’s caused by an excess of acidity instead. (While some acidity is a good thing, too much can weaken the gluten network as well.) If yeast activity was slower than optimal, acid production might outpace CO2 production and the dough would over-acidify before it is fully proofed. (Such a dough would take longer to ripen than it would under normal conditions, something to pay attention to.)

Whatever the underlying reasons—I’ll let you know if I ever sort it out—this is something you should look out for when you are trying to gauge the health of your starter and decide whether or not it is time to shift from room temperature feedings to refrigerator storage. If your crumb looks more like the first image, then it’s a sign that your starter isn't 100% there yet, and you should continue feeding it at room temperature.

The good news is that loaves that look like that first one are still delicious (the friend that sent me that photo had no complaints about the loaf itself).

- Andrew

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.