On Internal Temperatures in Bread Baking

Trust your eyes, not your thermometer!

Table of Contents

I just shared this to the Breaducation Testers group, but I thought it would be useful for everyone here too, so I am crossposting here as a Wordloaf “extra.” (We’ll still have our regularly-scheduled Wednesday post tomorrow too.)

It was inspired because I’d noticed that some of the breads people have been sharing over there looked far more pale than mine, and I realized I might be at fault for this, since I do give internal temperatures as endpoints in my recipes. I think they are useful to include, but to be honest, like most bakers, I almost never use a thermometer when baking bread1 (This was in a footnote originally, but it deserves more visibility: The one exception is highly-enriched breads, particularly those that contain lots of sugar, like brioche. Not only are these ultra-plush breads prone to collapsing if they aren't 100% set internally, their high sugar content makes prone to darkening quickly, which can fool you into thinking they are done before they really are, so temping is really the only way to be sure.)

Here’s why: Internal temperature is a secondary indicator of doneness, not a primary one. The primary one is the visual appearance of the loaf—I use my eyes as the best “thermometer,” and I bake my loaves until they look dark enough. (I tend to prefer my loaves “bien cuit,” and take them pretty dark. Others prefer a lighter bake, but there is a limit to just how pale you can get away with before a loaf suffers.)

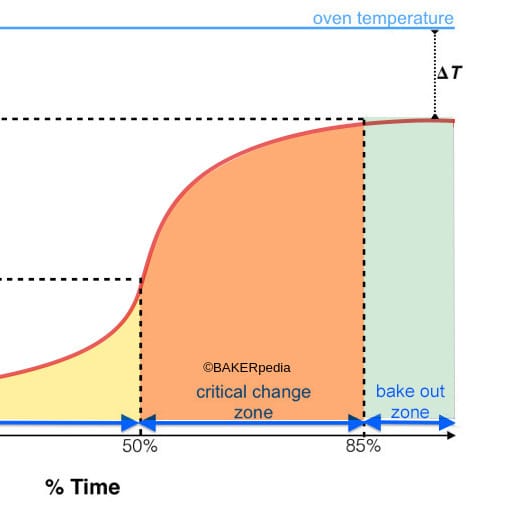

Here’s why: The temperature on the inside of a loaf cannot exceed 212˚F, since that’s the boiling point of water (in reality, it doesn’t ever exceed 210˚F). More importantly, the curve of rising temperature during baking is not linear— it is more of an S, like this:

See how that last 15% (the “bake out zone“) is nearly flat? The curve shows that the internal temperature of a bread approaches the maximum temperature long before the bread is “done” baking. In other words, the inside of the bread is “cooked” well before the end of the bake.

So why not take it out earlier? Because the bread is not fully cooked on the outside! It is as simple as that. Not only does a darker color on the crust equal better flavor and a crisper texture, it helps ensure the crust is firm enough to prevent the loaf from collapsing as it cools (this is especially true for soft, enriched breads like the ones we have been making here so far).

The other takeaway from that curve is that the internal temperature hangs out at or near the max temp for a long time, which means that you cannot really overcook a loaf on the inside while you wait for the crust to catch up.

When I was at ATK, I did an experiment to demonstrate this:

[W]e baked three loaves each of various styles, including enriched types containing fat and eggs and lean types containing just flour, water, and salt. We pulled one loaf of each type from the oven when it was 5 degrees shy of its recommended temperature (typically 190 degrees for enriched breads and 205 degrees for lean breads), one when it was 5 degrees past its recommended temperature, and one when it was right on the nose.

On the inside, all the loaves were just as they should be—neither too wet nor too dry and perfectly moist. But the exteriors were a different story: Many of the low-temperature loaves were soft-crusted and pale and lacked flavor, while some of the high-temperature ones were too hard and slightly burnt on the underside.

In other words, the problem with an underbaked or overbaked loaf is in the crust, not the crumb, and you should bake until the loaf looks right, first and foremost and not rely on a thermometer to tell you when to stop baking.

I like to think of internal temperatures as a “training wheels” technique for beginning bakers who want some reassurance that the loaf is cooked through. Once you bake enough loaves, you’ll come to trust your eyes and leave the thermometer behind.

I hope this helps!

—Andrew

The one exception is with super highly-enriched breads like brioche, when I want to be 100% sure the crumb is set so the loaf doesn’t collapse on cooling. ↩

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.