Nourishing

An interview with Brant Stewart of Mavia Bakery, a social enterprise in Beirut

Table of Contents

Brant Stewart started Mavia Bakery in Lebanon, in 2017. This social enterprise has a mission of using bread and baking to break down cultural barriers, and is an offshoot of earlier work to support Syrian refugees.

Brant started The Sadalsuud Foundation as he, a filmmaker and photographer, saw the refugee crisis unfold. Raised in the Mormon church, he gained a strong sense of service, and felt called to assist Syrian children in accessing education.

Sadalsuud is the name of a star in the Aquarius constellation. Translated from Arabic, Sadalsuud means “luckiest of the lucky,” and refers to the star’s rising with the sun when winter has passed. As Brant became aware of the tremendous psychological pressure Syrians were experiencing in Lebanon, he sought ways to help Syrians and Lebanese understand each other. The bakery was born in this shift, rising from an obsession with baking naturally leavened bread.

Adrian Hale, a writer, first taught him to bake sourdough, and he developed a solid community of baking friends to help him set up Sadalsuud Bakery. Among them was Sarah Owens, the author of several books on sourdough baking and fermentation in general. In January 2017, Sarah came to Tripoli, in the north of Lebanon, for a month to help train bakers, and help establish the bakery in a community kitchen. Rose Wilde, Los Angeles bread and pastry baker extraordinaire, also leant her passions to the project. After two and a half years, the bakery moved to Beirut, where it took a new, also symbolic name, Mavia, which refers to a substance in the trees that brings them back to life in spring.

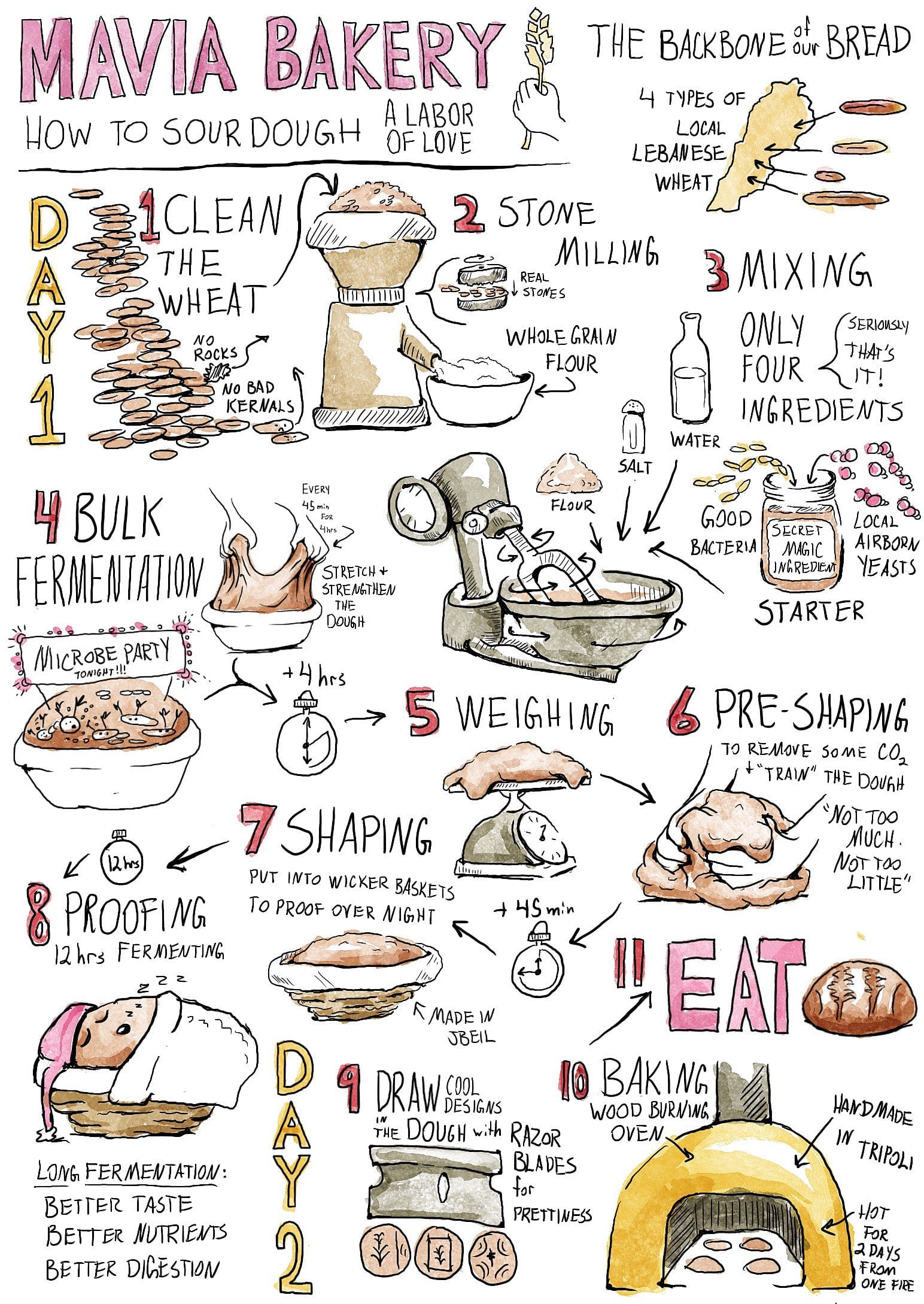

The bakery staff has always been a mixture of women from different backgrounds, as part of the goal to foster understanding. Lebanese wheat entered the project along the way. Baking bread near the cradle of wheat, of course he got curious about local wheats. He’s planted some varieties, and set up a small milling operation in the Bekaa Valley.

But it wasn’t the flour and wheat that first excited me about this project—I loved that it was a bakery with a plan to build community. When I got obsessed with flour in 2011, I started hearing about the idea of bread building community. Bread, and the various jobs of growing, milling, and baking grains had drawn us together as people over and over again, and I was curious if this intersection of labors—or maybe, a need for collaborative work in a siloed world—was responsible for the revival of regional grain production. Once I heard of a bakery that was dedicated to building community, within the bakers and for the people who ate their bread, I was hooked.

I kept my eye on the bakery through social media, watching how it fared during the pandemic. In August 2020, there was a horrible explosion near Lebanon’s primary grain silos in the port of Beirut. The city was in shambles, and Brant mentally accepted that the bakery would close. How could it not? But through fundraising, the bakery survived.

I heard more about this time when Brant spoke at a remote session of The Kneading Conference. During that hour and a half, we attendees hung on his every word. There is so much that we—Americans, and maybe Westerners more broadly—don’t know about everyday life in other contexts. Brant illustrated the depth of disruption and chaos that are common in Lebanon and helped us see how this grain-based intervention was functioning.

I was happy to have an excuse to interview him for Wordloaf. We spoke on a Saturday in late February while he was in Turkey. Since our conversation, Mavia has announced a project to raise funds for Gaza and is inviting artists and bakers to contribute to a digital cookbook. You can bet that I’m offering anything—an essay, or a recipe, or just a little bakery love song from afar. Keep your eyes peeled for the eventual project, and in the meantime, thanks for reading this.

Amy Halloran: Can you tell me about your connections to Beirut and Lebanon, and why and when you left?

Brant Stewart: It still feels like my home, even though it feels very unsafe. For better, for worse, I've never lived in a place where I've had more of a sense of community in my life. Everyone knows me as the baker and the farmer and whatever else and it's a huge part of me but so many people have moved away from Lebanon because of the financial situation. No one wants to move away, including myself. I didn't really want to. I felt like I had to, you know.

AH: I can definitely hear reluctance, maybe defeat in your voice at the choice that you had to make. But the bakery is still there. Can you review its timeline?

BS: In 2017 we opened, and eventually, working in the community kitchen was tough for a number of reasons, including because we were bringing the bread to sell in Beirut. So, in 2019 I decided to move the bakery to the city. I signed the lease in the summer of 2019 and then all the economic stuff started that fall. But it took a while to get the bakery going, so we didn’t open until March of 2020, right during the pandemic.

I still had one employee from before, but because of COVID there were no buses, and I was nervous (to expose them). So when I started in Beirut, it was just me and I was basically just baking. I would prep one day a week and then bake one day a week and I would take orders throughout the week, you know? So it started slow, but just getting to the opening was already really slow going.

The economic crisis really started in the fall of 2019 and we had what we called the revolution in Lebanon, which was in October. This is when everything kind of came to a head. There were massive protests, and they were bigger than they'd ever had. The day after the protests started was the day the plumbers were supposed to come and hook up the water in the bakery, and so they couldn't end up coming because all the roads were blocked. So this is how the bakery started in Beirut. It was in the midst of this crazy, unparalleled protesting, you know. So it was kind of slow-going.

Looking back on it. I was very depressed. I tried to raise the money to open the bakery and to move, and I didn't manage to raise enough so my grandparents lent me some money. And seeing everything going down the toilet because of the economic situation—I was like, oh my gosh, I can't pay this money back. That's just crazy. But then, every month in 2020 we were making more and more money, things were going well. Then the explosion happened (on August 4th) and I was very close to just leaving and calling it quits. My friend said, no, let's try and raise some money and it was amazing to see the outpouring of support. And we were only still functioning because of the explosion, which is crazy to say.

AH: Because the fundraising afterward stabilized things?

BS: Well, that that brought us so many donations, because I think everyone wanted some connection to donate to Lebanon. I already had a fundraiser online from the year before, so it was very easy to start raising money again. With the donation money I paid back the loan. We still have some of the donation money and are using it when we need. But the bakery has become self-sufficient, which is great. So it's taken a while to get going, but I figure if we can survive in the economic crisis and an explosion and a war and all these things, that hopefully we will continue.

AH: You didn't even say pandemic in that list!

BS: Oh yeah, forget about the pandemic. That's true.

AH: Oh my gosh. That's crazy. Tell me about the Sadalsuud Foundation and how it links to the bakery now, if at all.

BS: For years, I was focused on education with the nonprofit. And once I moved the bakery to Beirut, my desire and my ability to continue raising money was waning. Kinda, who is now running the bakery and who has become my business partner said look, we need to make this more of a business. But everything in this bakery has been donated to us, so (I have qualms) [?? parens] about turning this into a business. Clearly. But the reality is we need to structure this in a way that's going to allow it to continue for as long as possible, right, and to continue to employ women.

I got a larger grant at the end of 2019 for the school. And we had a larger program focused on prevention of gender-based violence and early childhood marriage. We had about 60 girls in school that that fall, and that was when all the economic stuff started. And I realized that I had to decide if I'm going to focus on the school or focus on the bakery. And I chose the bakery for better or for worse. I'm not actively raising money anymore, and I'm not really planning to anytime soon. We need to focus on other initiatives, including more urgently on Gaza, I haven't figured out what to do exactly yet, but I feel like we have to continue to pay back all the goodwill that people showed us as an entity and to hopefully inspire people and to raise some money to help people.

AH: I heard that the war in Gaza impacted planting wheat, but how has it affected the bakery?

BS: To be honest, I don't know if it has. The reality is everyone in Lebanon is so used to this. It's sad but it's just a part of life. There's never too much time that passes before there's the next thing that happens, you know? Just the other day Israeli jets flew over Beirut and, frightening people.

In terms of the wheat planting, it was just me, it wasn't the country in general. If there's anything I know about Lebanon, it's the most unpredictable place I've ever encountered in the world. So the minute you think you understand things is when you don't. And I've seen how things can just change very, very quickly. You know, I felt so safe before the explosion. I never imagined something like that could happen. Never.

So not planting last fall was just because of my work. I'm working this full-time job with a nonprofit. I'm managing programs in two countries. And my mental space has just been so diverted. Now, I should say that I just didn't want to risk getting stuck there. I didn't have the time, practically speaking, so I wouldn't say it was necessarily because of the war.

AH: What does the bakery look like day-to-day?

BS: We have 5 full time women working. We have Dunya, who was the very first person I hired. She's a widow from Tripoli, and she's working as much as she wants to, which is three days a week. She'll commute down from Tripoli. It's a long trip, an hour and a half each way. She is one of two employees in Tripoli who lasted those initial 2 1/2 years. Obaida was the other. Obaida met a guy on Instagram because I posted a picture of her on the nonprofit account and he was following the nonprofit. He's a baker in Turkey. So, they met on Instagram and he actually came to Lebanon and baked with us, and we met him. He's super nice. They got married, and now she lives in Turkey.

We have two Syrian women, they've been with us for a couple of years and they're both amazing. We had an amazing woman, Martha who is Nigerian, and sadly she just left at the end of January. She was such a great part of the team. She just moved to Ghana, and I don't think we found another full-time person to replace her. There’s also now a woman named Ola working the front of the house. Kinda was once front of house, and she’s now the primary owner and runs the bakery. Also, she opened a new bar last year, and a lot of her attention and time go to the new place as well.

We’ve continued with the same theme of looking for women who need work and who maybe are more marginalized than others, so there's a lot of challenges, because typically, these women have children they need to support. Typically, they're a little more conservative. They're not used to working in the trendy kind of hipster area where the bakery is, and mostly, these women haven't had a proper job before. So it's challenging, but we're sticking with our mission of looking for women who really, really need these jobs, and trying to cultivate a strong sense of diversity within the workforce in the bakery. The only line that we don't cross is the gender line, although we have a woman who identifies as trans and she was going to start coming in in the evenings and baking cakes and things. She works at the bar next door. And it's been nice having her as well because she's so different from all the other women who are a lot more conservative and not used to maybe being around trans people, you know.

AH: Do you know if Mavia has inspired other bakeries?

BS: I don’t know. But I will say that who we are as an organization and as the bakery really appeals to people in Beirut, and they believe in what we do. We have so much great support not only because the products are good but because there's a lot of layers to what we do—in terms of cultural diversity and the biodiversity that we're trying to cultivate in the wheat and the fact that we're growing wheat without inputs. These mirrors between biological biodiversity and cultural diversity are very similar and I think any diverse system is more resilient and that is probably why we're still around.

AH: Talk about the wheat that you found.

BS: It was a long process of driving around, frankly in the Beqaa Valley looking for wheat. Whenever I was driving around, looking for farm equipment, I just asked people if they knew of anyone with wheat. We've settled on some really good wheats. We don't know much about them yet, sadly. But we're working with a few different types of bread wheat that are, as far as we know, from the Beqaa Valley. We have one called Bekaaii. We have another called Baalbeki, which is from Baalbek, which is also in the Bekaa Valley, and where the Baalbek ruins are.

We have a really nice bread wheat called Salamouni which is the most famous Lebanese wheat. We've just started incorporating that more into our bread. I'm kind of making a mix, we called the Mavia mix because why not? It’s our own little mix of all the different wheats that we're growing that we're using in our breads. We're using one modern cultivar, which was developed by ICARDA, which is the seed bank, the International Center for Agriculture in the Dry Areas. It’s the largest seed bank in the Middle East and was headquartered in Aleppo, and when the war broke out, it moved to Lebanon. I'm in touch with them now and we're trying to figure out a joint project together, maybe to start growing out other landraces that are in the gene bank but haven't made it into the system. Because the only way to really preserve wheat is to get it into people's bellies and to get it into the (agricultural) system. You know, because if it's just sitting in cold storage, what's the point?

They developed a type of wheat called Tannour, which is like tannour bread, made in a tandoor oven, and they developed it specifically to make tannour bread. So, we're using that in our pizza and it's a really nice kind of a softer wheat.

Then we have a couple of durums we're using, so we have one called Saragouli. In Lebanon, they say this wheat is from Italy. It's called Saragolla in Italy, it's quite a famous wheat. But I've realized what we're using is not the same thing that they have. The wheat kernels are much longer and ours is more normal durum with shorter kernels. It’s a really tasty wheat. We use that in our bread. We're also using Hourani, which is a landrace originally from Hauran, which is the plateau in the southern part of Syria. This is one of the more famous landraces and was found in an ancient Israeli temple in the Masada fortress. They found remnants of Hourani from thousands of years ago.

The most exciting wheat is called Meshmoul, it's a population wheat, so it is super genetically diverse. It's crazy in the field. You see it and you think there are hundreds of varieties growing together. One of my friends is a farmer from Rachaya and he gave me the seed and said his grandfather started growing two types of wheat together, mixing these because that's what made the best Arabic bread. Over the years it really became genetically diverse. And so we're using that in the bread as well. It's beautiful and Meshmoul in Arabic means a little bit of everything.

I talked to ICARDA about it as well and they know Meshmoul and they're really excited about it and, I think, are studying it now. Other than that, I don’t there's other populations in Lebanon, but there may be because in Lebanon it's really hard to get information. It's not usually written down. The information is transmitted orally, so it's a kind of place where there's probably so much more out there, but you won't realize it until you go and find the person who has it you know. Like looking for a needle in a haystack, but you don't even know where the haystack is.

Oh, we have one more type of wheat called Bayadi, which means white. That’s the only soft wheat that I found in Lebanon. I found it from a farmer in a town called Biri. It was very random. I think I was buying some rope because I planted a biodiversity field and was trying to mark it. And when I asked, people are like, oh, the guy across the street, he has some in his garage there. So I walked over and I bought some from him. And it's beautiful. We use that for all of our sweets.

AH: That’s wild. In a place where durum (a hard wheat) grows really well, you wouldn't think that a soft wheat would do well.

BS: But this guy grows it on the top of this little mountain where he lives and that's the only place I ever found it.

AH: How is the milling happening?

BS: The mill is not in Beirut, but our miller, he’s working for us part time and we usually make arrangements for friends to bring flour in their car.

AH: Where does the bran go?

BS: So we're not sifting. We're not using 100% of our own wheat yet, we're also using wheat from a mill called Bakalian in Beirut. We’re using their bread flour, but that's imported commodity grain. The local wheats don't have the strength. If I had my way, I would only be using our wheat, but I would have to be there (to pay attention to the doughs). And it would take our customers really liking our whole wheat bread, but it's a very few people who want to eat that, unfortunately.

AH: That's nearly universal, I think.

BS: So all the flour that we use we're not actually sifting. We will sift it for customers, we have some other people coming to mill flour. And they typically want us to sift it, and I've taken the bran to the bakery next to the mill. They use it for dusting, and we incorporate it into our whole wheat bread as well. I'm using Dawn Woodward's whole wheat bread recipe, she soaks some of the bran in boiling water and then incorporates that back into the bread.

AH: Oh that's great. So do you have other projects on the horizon?

BS: I really have the desire to open up a new bakery, and maybe it will be very similar to Mavia. I'm thinking to do it in Greece. But I want to take this idea of Mavia and actually bump it up a level even more of like what it's doing for the community, what it's doing for the employees, and very intentionally craft a space, and sourcing more local ingredients. I’m thinking about incorporating ceramics into that.

AH: There’s such a parallel in the handwork of potters and bakers.

BS: Yes.

AH: Can you reflect the act of baking as an individual and then what a bakery does within a community?

BS: Well, I think all of us who are involved in bread realize its inherent importance in society. I guess the word I’d use to describe it is nourishing, and I think that's what the bakery does, not only with the things we sell, but the whole story of what we're trying to accomplish. The physical things are made with a lot of love and intention and speak to Lebanon as well. We’re using these wheats that are from there, and people aren't used to that at all. They're really surprised and since the economic crisis, a lot of importing has kind of ceased. People have started growing more things, and there’s a lot more development of local products. I see the space and I see the bread as a source of, of energy. In fact, one of the meanings of the name Mavia is the substance that enters the trees in the springtime and brings them back to life, makes them bloom. And so, I guess a source of energy and nourishment.

AH: That’s great. So, what's your favorite bread to make these days?

BS: I’m using our flour from Lebanon. There’s a farm actually in Lebanon, a group of French farmers that are growing Irani, an Iranian wheat, a durum. It's really tasty. So I've been using that in my bread recently, and including the Meshmoul as well. I don’t do anything fancy, just make it, but the flours taste great.

More about Mavia

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.