Croissants All Day, All Night

An interview with Kate Reid, of Lune Croissanterie

Table of Contents

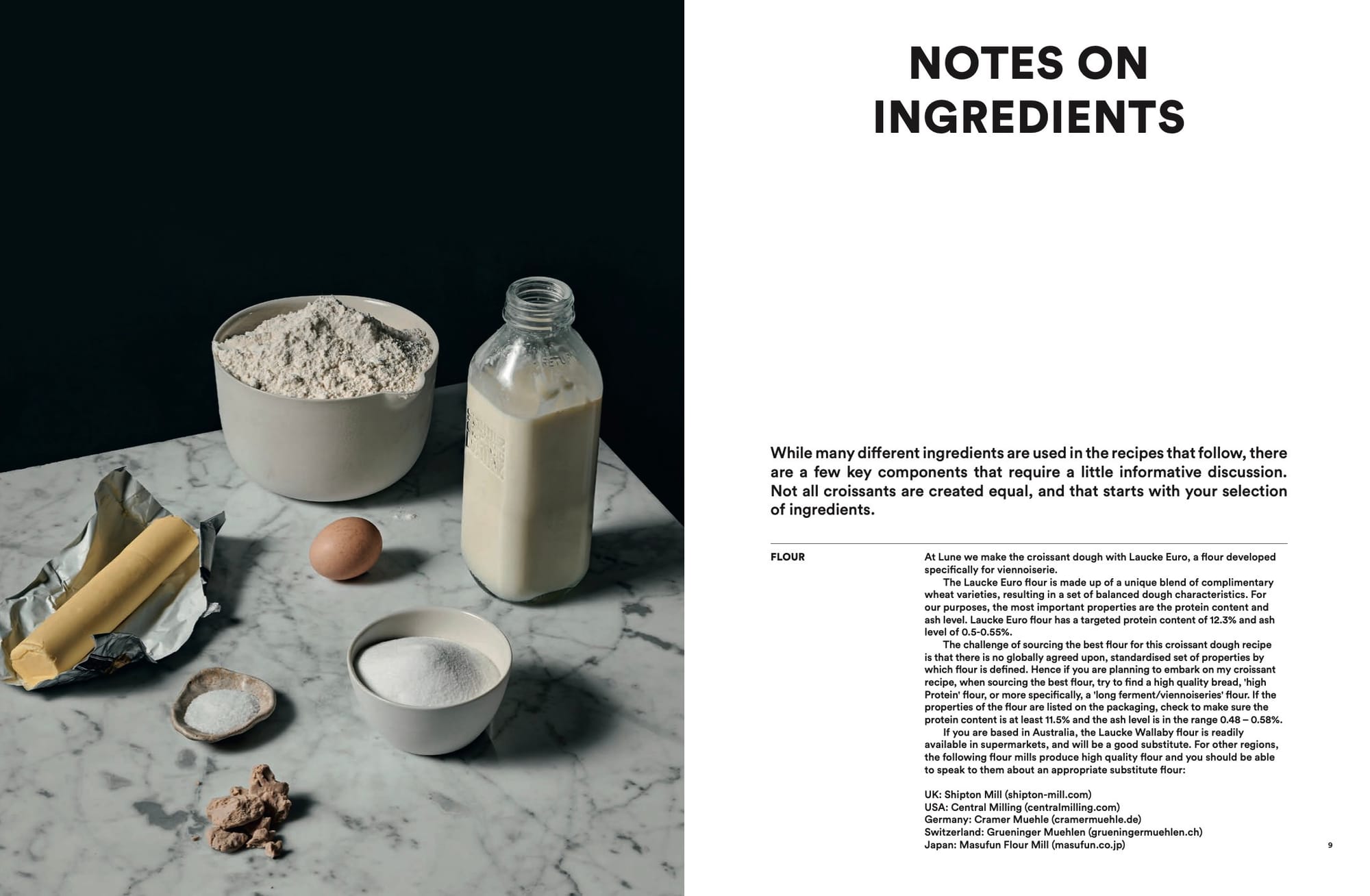

There are some cookbooks that you open for the first time and immediately know will occupy a permanent, special place in your library, and Lune: Croissants All Day, All Night, by Kate Reid—owner and founder of Melbourne’s Lune Croissanterie—is one of them. Everything about this book is a dream: The cool, elegant design, the gorgeous, slightly askew imagery, the whimsical, inventive recipes, and most of all, the method it presents, clearly and vividly laid-out.

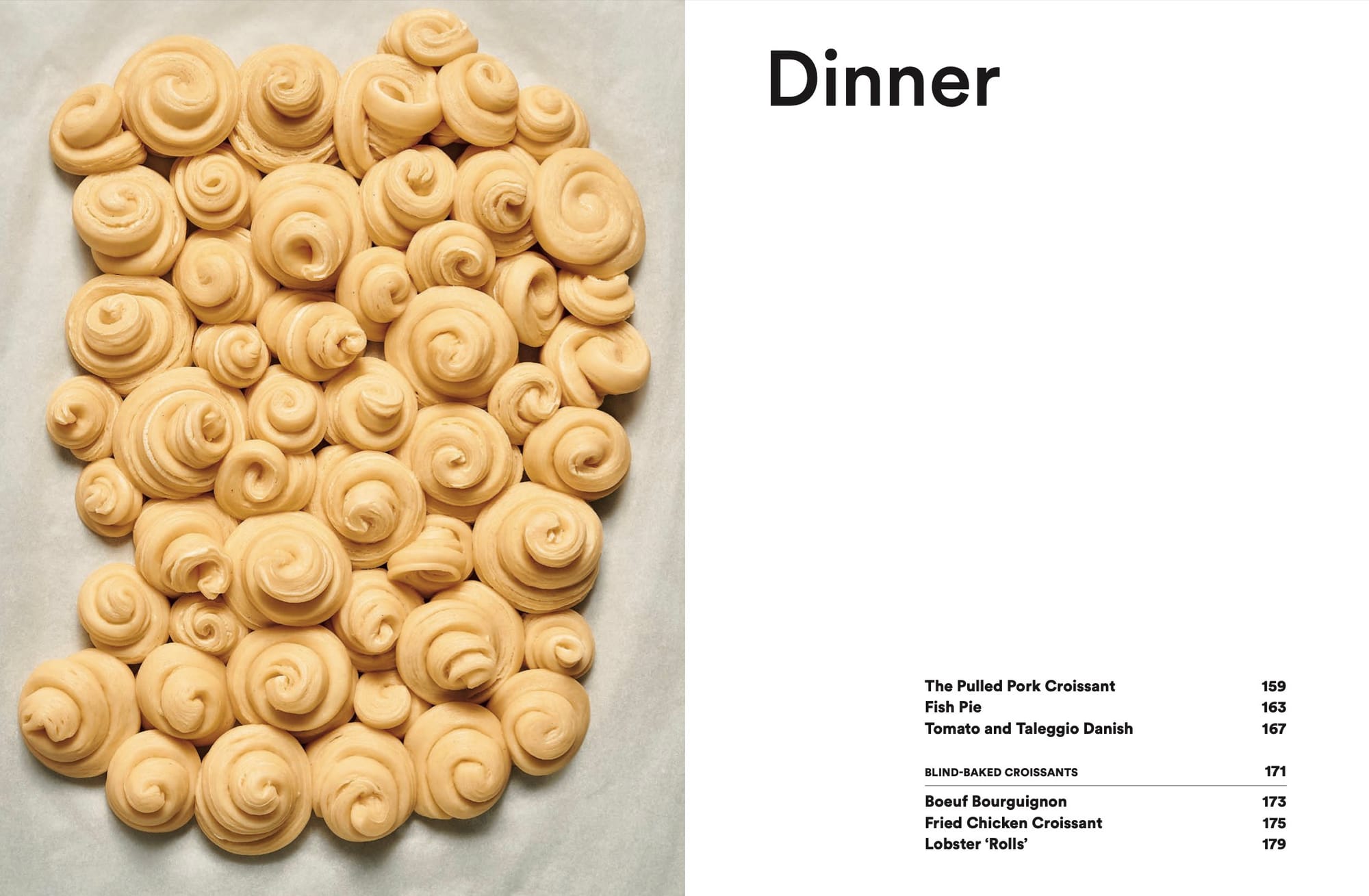

Lune is about one thing and one thing only: How to make croissants and other croissant-adjacent products, like escargot, cruffins, and kouign amann. It contains some 60 recipes for filled or flavored variations on the theme, like Pumpkin Pie Cruffins, Pepperoni Pizza Escargots, and Pulled Pork Croissants. But the heart of the book is its first 40 pages or so, which present the technical information needed to make these notoriously difficult-to-pull-off pastries at home. The method is unlike any others, and was created by Kate to specifically address some of the problems that aspiring home croissant-makers face when having to make the pastries by hand rather than with a mechanical sheeter. (I’ve tested the method myself, and can vouch for its effectiveness and efficiency.)

I recently spoke with Kate about how she went from working in aerodynamics for Formula One racers to the croissant expert she is today, how the Lune cookbook was crafted, and how she sorted out the unusual method it contains. It’s a long interview, but it was so much fun that I wanted to share it in full with you all. I hope you enjoy it as much as I did. (And stay tuned for a second email in a bit, where I’ll have copies of Lune to give away to two lucky subscribers.)

—Andrew

Andrew: I haven't fallen in love with a cookbook like Lune a long time, I want to say that outright. It’s not just a practical guide to doing something, it's a thing of beauty at the same time. I love it. I’ve sung its praises high and low, everywhere I can.

Kate: Oh, thank you. That makes me feel so humble to hear someone like you say that. I'm very proud of it. I am an absolute control freak, which will probably come as no surprise. I think a lot of chef authors submit their recipes or get their sous chef to submit the recipes, and then they're like, "Okay, cool. Now I've got a book out there." But I basically art directed the photoshoots, [and] I insisted that the publishers give me the working copy of the manuscript so I could play with the design and lay it out in the way that I would. [The publisher, Hardie Grant, said,] "We don't normally do that for an author." "I used to design a Formula One car, [I told them.] "I promise, I'm not going to ruin the manuscript on you!” It was a true labor of love.

Andrew: I feel like you can really see that this book was created visually. If you're going to put a dynamic process into a two-dimensional linear book, then you really have to translate that in a way that you can then kind of recreate in your mind the process in a three-dimensional way. It does a really good job of that, of telling the story of how you make croissants.

Kate: Thank you. It's funny that you mention this idea of "three-dimensional." When I got back from France, I bought two books [in which] a croissant was one of the 100 recipes in the book. But dedicating two or three pages in an entire book about baking to croissants is not enough. And when I tried these two different recipes from the books, the dough was a bit crumbly, and it felt cold and it was hard to roll out. And you know, every time I'd get to the point where I had to roll out for the final sheet of pastry, the gluten had developed so much that it kept springing back. And I remember thinking, "I'm doing something wrong here. Because surely, this isn't how it's meant to be. But I don't know what I've done wrong."

But now after 10 years of specializing in croissants, and then the process of going through writing the book myself, I now know that it wasn't actually me doing anything wrong, it was just the author that had written that recipe had just missed so much detail in the process.

But now after 10 years of specializing in croissants, and then the process of going through writing the book myself, I now know that it wasn't actually me doing anything wrong, it was just that the author that had written that recipe had just missed so much detail in the process. It's really hard to just read words and then understand visually what it needs to look like. So for me the goal with writing the book was I wanted people to feel like I was literally standing there in the kitchen with them talking them through it and showing them how to do it.

Andrew: Can you talk just briefly about how you first how you ended up in Formula One racing early in your career, and then how that translated into your becoming a pastry chef, and a croissant chef specifically?

Kate: So I'm going to give you the whole story and you can just decide what you include. I don't talk about the middle part in my book at all, because I don't think it's relevant to the beauty of the book.

I discovered Formula One when I was a kid, I'm a real daddy's girl and we're still best mates, I love my dad so much. We really bonded over watching motor racing when I was a little kid. The Formula One season runs in the northern hemisphere summer, around Europe and the States, [when] it's winter in Australia, and the race is run in the middle of the night. So he'd let me stay up late on a Sunday night and we'd make tea and toast with Vegemite. We'd sit with a fire on and watch this incredibly exciting technical sport travel around the world. And it was an excuse to stay up late and hang out with my dad. Through that I fell in love with Formula One.

And then the Grand Prix started running in Melbourne in 1996, and I was 14 years old at the time. Dad bought me a ticket, and we went along together. I remember [the cars] had V10 in engines at the time, it was this high pitch squeal, so loud that you needed to wear earplugs. And they were just so fast that you couldn't even lock eyes on it when when it went past you on the track. And I just remember being so enamored by the technology that would be required to create something like that. I just knew that day that my career had to be in Formula One designing the cars.

I was already good at maths and sciences at school, but I just started to focus on that, and work towards getting into aerospace engineering. So I ended up getting a degree in aerospace engineering. And a year out of uni, I was offered a job with the Williams F1 team as an aerodynamicist. Still to this day, for me, aerodynamics is the most beautiful of all the sciences. It's so visually stunning and pleasing to watch air travel around an object and understand how that can affect the forces and the movement of something.

I had a pretty overactive imagination when I was 14 years old, and I painted this picture of what a life working in Formula One would look like. I imagined that it would be the greatest minds who've studied in their specific fields coming together and collaborating and brainstorming on a very exciting, fast moving design of a car that gets to travel around the world. An incredibly dynamic working environment that would be motivating, inspiring, and very fulfilling in a professional sense.

[But] When I finally was offered a job in F1, the reality of the working environment was very different to what I'd imagined. At the time, the team that I worked for were probably mid-pack, so they weren't winning races anymore. And when you're not winning, there's a lot of pressure from people high up in the team and the people that are putting the money into it to improve the car. And it's negative pressure. They use scare tactics a lot. People would patrol the offices late at night to check to see if we were putting in the hours—like 16, 18 hours a day in front of a computer. Conversation in the office was discouraged.

It was incredibly unmotivating and not collaborative, even in a technical sense. You know, if we trialed an idea in the wind tunnel and it didn't work, we didn't do any follow up to understand why it didn't work, [we'd] just scrap the idea. Such was the fast-paced nature of finding a solution. And I felt like we lost so many opportunities to understand why something hadn't worked, and learn from it and maybe get something good out of that.

Anyway, I found myself really unhappy and very unfulfilled and I developed depression, but then that manifested in an eating disorder. And I got really sick. I developed anorexia, which it wasn't about body image, it was about lack of control in all the big areas of my life. And the two things that I could control were what I ate and how much I exercised. I started to treat my body like how I'd probably imagined designing an F1 car. I recorded everything that I ate, how much exercise I did, I weighed myself every day, I had crazy spreadsheets and graphs and tracked my progress. I'm somebody that really feeds off measurable progress. That's pretty linear, you start eating less and exercising more, and you get a number of measurable results. And at some point in time, you become very, very sick, and it's incredibly unhealthy.

It wasn't my choice to leave Formula One. My partner at the time just got so worried about me that he called my mum and dad and said, Look, I'm really worried about Kate, I don't think she should be in the UK anymore. So Dad flew over, packed up my life, and and essentially, that ended my Formula One career. At that point in time, I was so unhappy and so sick that I didn't have good feelings about F1. I didn't want to be in the industry, but I think had that not pulled the plug, I'm probably stubborn and determined enough that I might have stuck it out just to prove a point.

And the irony of an eating disorder is all you can think about is food, you know, you're starving, so your body is sending signals to your brain all day to fuel it. And when you're so hungry, you don't dream about eating a lettuce leaf, you go to the thing that you love the most. And for me, that's baked goods.

But inadvertently, that meant I got a clean slate to start again. And the irony of an eating disorder is all you can think about is food, you know, you're starving, so your body is sending signals to your brain all day to fuel it. And when you're so hungry, you don't dream about eating a lettuce leaf, you go to the thing that you love the most. And for me, that's baked goods. And I started baking at home after a terrible day in the office.

One of my favorite things about baking is you look at the lineup of raw ingredients that you start with on your bench, and none of them are edible. You can't snack on raw flour or salt or sugar. But through this very methodical, technical process—it's like science and magic—the sum of the parts of a baked good are just so much more than their individual parts. And at the end of the process, you open the oven and you pull out this glorious-smelling thing that that just makes people happy. I really started to live vicariously through the process of baking, even just the procuring of the ingredients, the getting lost in the mindfulness of following the recipe. And then there's the added benefit that you'd take it to work the next day, and at 10:30, everyone would stop and make a cup of tea and have some of the brownie that you'd made or a bit of cake. It was actually the only time the whole [Formula One] office really felt communal and it put a smile on everyone's face. So I guess I discovered my love of baking through that.

When I came back to Australia, I decided that I wanted to pursue a career in baking, and I got a job at this beautiful little cafe in a neighborhood. This gorgeous woman Mary entrusted me with the baking in her kitchen. She was very supportive and nurtured me and I learned an awful lot through her. But I was working for her baking simpler things like cakes and tarts. And I was starting to get a bit toey1 do something a bit more technical, and I think that French pastry is one of the most technical pastry cuisines on the planet.

It was a really close-up photo and you could see every perfect layer. It was like those Scratch-and sniff-stickers from when you were a kid where if you scratched the page you would have smelled toasty flour and butter. I was so hypnotized by this photo that I literally closed the book and walked up to the nearest travel agent and booked a ticket to Paris.

I was starting to do a bit of reading about it, and I ordered this book called Paris Patisseries: History, Shops, Recipes. It’s a collection of the best patisseries and boulangeries in Paris. It's got a bit of a history about the shop, and then it features a recipe from it. I was excitedly sitting on the floor of the living room, and I opened the book randomly to this double-page photo of pain au chocolat on the counter in a boulangerie in Paris. And it was a really close-up photo and you could see every perfect layer. It was like those Scratch-and sniff-stickers from when you were a kid where if you scratched the page you would have smelled toasty flour and butter. I was so hypnotized by this photo that I literally closed the book and walked up to the nearest travel agent and booked a ticket to Paris.

Andrew: Is that literally true? The next thing you did was book a ticket to Paris?

Kate: Literally.

And then I ended up in Paris. And the last day that I was in Paris I decided that I would go to the boulangerie where the photo had been taken, [Du Pain et Des Idees], and that was a transformative experience. I'd been in a million bakeries in my life, but never with my eyes wide open like they were that day. I just took in everything, starting from the line of elegant people snaking out the door, all just having their little moment of anticipation of what they were going to order. And then the actual space of this shop, this beautiful restored Belle Epoque boulangerie in the 10th. And then the counter—there were the pain au chocolat that were in the photo, but then this fanned array of croissants on a cooling rack, and six or seven different varieties of escargot.

I got to the front of the counter and the vendeuse, and I tried to explain to her in broken French that I'd booked this ticket on a whim after seeing a photo in a book. And I must not have been doing a very good job [of explaining myself] because she went out the back and got Christophe Vasseur, the founder and owner of Du Pain. I think he'd spent some time in Australia and America. He'd previously worked in the fashion industry, but he came from a long line of bakers. At some point in his [own] career, he felt burnt out, so he decided to follow the family tradition and do an apprenticeship in baking. And he'd found this site and fully restored it and opened his own bakery.

So I explained to him the story about seeing the photo and booking the ticket to Paris. And he wrapped up a few pastries for me and said, "Look, these are on me. What a great story, I'd love for you to just enjoy these." So I took them up to the Sacre Coeur, sat on the steps, and looked over Paris and just had this like wild experience trying these incredible pastries for the first time.

Having had the whole experience of being in the bakery, I really couldn't forget about it. We went to the south of France the following day, and I couldn't get Du Pain out of my head. We checked into our hotel and I [immediately] went and I sent Christophe an email. I thanked him for the pastries and the experience, and at the end, I just thought, “I may as well ask.” And so I asked him if they ever take apprentices. And he wrote back to me within about an hour. And he said, "Look, we normally don't, especially considering you don't speak French. It's a very small bakery. And we all speak French here." But he said, "For some reason, I can see the same passion and motivation in you that was in me. So yeah, when would you like to start?"

So I got handed this incredible opportunity to go and learn from one of the best in Paris. And it ended up we decided that I would do a three-month stage first, and at the end of it assess my competence in the bakery and how I was going with my French. And then also whether it was something that I wanted to pursue a full apprenticeship or not.

So I headed over to Paris about four or five months after that initial visit to Du Pain. And living in Paris with no salary is not easy. I wasn't exactly minted from my time in Formula One, where they were paying me 30,000 pounds a year.

Looking back on it, [the month I spent at Du Pain] might be the most concentrated period of learning I've ever done in my life, and that's saying a lot for someone that studied aerospace engineering.

Looking back on it, [the month I spent at Du Pain] might be the most concentrated period of learning I've ever done in my life, and that's saying a lot for someone that studied aerospace engineering. I was learning a whole new art and technique, and a lot of it was done visually. So your every sense had to be switched on, for the whole day of work. I was watching what the pastry chefs were doing, but at the same time I was also just desperately trying to pick up French. I was learning this new technique with pastry at the same time as learning a new language.

And then, in general, the job was just so physical—all the storage at Du Pain is in a basement, and there's this narrow little spiral staircase up to the ground floor where all the baking is done and the shop. And then there's another narrow spiral staircase that goes up to the first floor where the raw pastry kitchen is. And we were hauling 25 kilo bags of flour from the basement up to the first floor. And I'd get home from a 10-hour day at the bakery, and I was physically and mentally exhausted, but so happy and fulfilled with what I was learning. It was a pretty special period of my life. And although it was a short period of time, it was an incredibly impactful and transformational period.

At some point [during the stage] I spoke to Christophe and he said, "Look you're picking it up really quickly, you're actually being a useful member of the team." And we spoke about me doing an apprenticeship. I went back to Melbourne to consider my options and figure out how I could get back to Paris. But moving your life to the other side of the world is not easy, and I'd already done it once with Formula One. The prospect of moving it again, [once] I was back safe in Melbourne, in the comforts of my own city, seemed like a big jump again.

So I started becoming pretty obsessive about finding what I thought was the best croissant in Melbourne, something that replicated or came close to what I'd experienced in Paris. I'd spend my days off from work just traipsing around Melbourne to every bakery, and nothing came close to what I'd experienced in Paris. And I think I just ended up one day thinking, “It's not out there, so maybe I should do it. I've got all the knowledge.” So I spent what what was left of my life savings, and I signed the lease on a little shop, and I bought all the bakery equipment.

I made the dough and I tipped it out on the bench. I remember looking at it and going, “Oh my god, I've actually got no idea what to do with it next—I've never used a laminator, I've never flattened a sheet of butter, I've never marked and cut a batch of croissants before!” I had no idea what to do.

And I had this moment where it was finally all set up. My job in Paris had been to make the croissant dough. And then I begged the head pastry chef to teach me how to roll the croissants. But that was all I'd done. And I made the dough and I tipped it out on the bench. I remember looking at it and going, “Oh my god, I've actually got no idea what to do with it next—I've never used a laminator, I've never flattened a sheet of butter, I've never marked and cut a batch of croissants before!” I had no idea what to do.

And I think at that point in time, there was no going back. I had a bakery set up around me and I'm like, "Okay, well, I'm just gonna have to figure this out." And I imagined what I wanted the end product to be like. And I just started working backwards and reverse-engineering the process. The technique that I landed on for making a Lune croissant is quite different to the classic French technique; it’s purely because I wasn't taught it, [that] I came up with it myself.

At Lune, because it's something that I innovated with an engineering mindset, every single day, every part of the process is open to critical analysis…if one of those chefs or kitchen hands, or anyone who works on the process, has an idea for how to improve it, whether it be the quality of the end product, or the efficiency without affecting the quality, we test it. And if it's better than what we're doing, it becomes a new part of the process.

The technique we use at Lune is not tied to that centuries-old process that's passed down from a master baker to an apprentice, like a religious process. At Lune, because it's something that I innovated with an engineering mindset, every single day, every part of the process is open to critical analysis. I've got 180 staff working for me now, and something like 70 chefs. And if one of those chefs or kitchen hands, or anyone who works on the process, has an idea for how to improve it, whether it be the quality of the end product, or the efficiency without affecting the quality, we test it. And if it's better than what we're doing, it becomes a new part of the process. So it's this constantly evolving way in which we make the croissants at Lune. I love that because it means that the pastries that we're making now, they're only ever going to get better. Perfect can be your goal and you'll never get there, because what is a perfect croissant? It's so subjective. But it's exciting to me that like in 20 or 30 years time the croissants we make at Lune are going to be so much better than what we're doing now.

Andrew: So it sounds like that experience of not knowing or thinking you knew something and then realizing you didn't know the thing and then having to figure it out yourself, while also not not feeling any kind attachment to tradition, sort of set you up to it again when it came to creating a version of the recipe for home bakers. So can you say something about how it is that you figured out what you needed to do differently when making croissants at home?

Kate: I had this idea that, with a rolling pin, it's really hard to roll out laminated dough, without stuff getting messy and the lamination breaking. At Lune, we don't sprinkle flour on any surface, it doesn't get sprinkled on the sheeter or on the bench. And I really wanted to carry that rule into the book, because I think that that has an enormous difference on the end quality of the product.

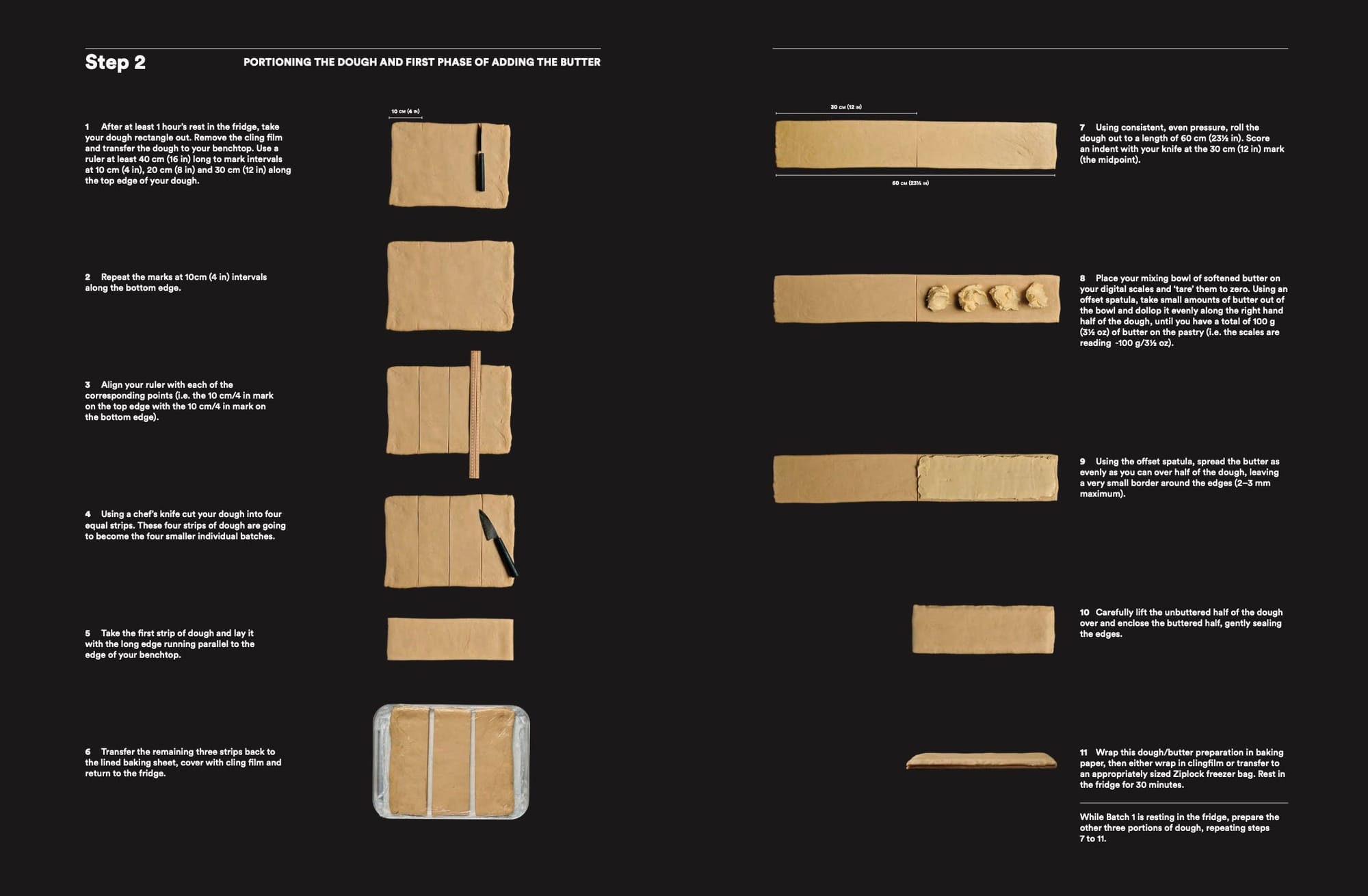

But rolling out dough that has butter laminated into it is very difficult. And I had this idea, “[What] if you could do a lot of the work before the butter got laminated into it?”

But rolling out dough that has butter laminated into it is very difficult. And I had this idea, “[What] if you could do a lot of the work before the butter got laminated into it?” The classic technique is you've got your square of dough, and then the square of butter, and you fold it in and then you roll it out. [But] If you've done the work rolling the dough out first, and then you can figure out a way to laminate the butter into it, already your first introduction of the butter into the dough, your first turn, is going to be not messy. And it's going to result in not having to add flour.

Obviously, we don't do it at Lune, but the home baker spreading softened butter—not melted, but at room temperature—with a palette knife, if you can get a really even spread across the dough, all you need to be doing is separating your layers of dough. It's really hard to keep the butter cold when you've created your your square of butter to laminate. But it's really easy to make sure that when you fold over the dough if you've spread it with a palette knife, and technically every part of that dough is separated by a layer of butter, you've created lamination, and the end product will be separated layers of dough and butter. And it doesn't have to be that millimeter perfect for the home baker. When I tested that technique at home, already I was like, "This is so much easier than when I got back from France and I bought the two books and I had tried it like the ‘bakery’ way…I can't believe people haven't thought about doing this before."

So I was testing these new laminating techniques and they were working to a certain extent. But when I got to that final rollout of the sheet of pastry before you cut and shape the pastries, I was still hitting roadblocks. At Lune we don't use a preferment, we kind of have a mother that that carries on the lineage of our croissant dough. In the past we've tried making a batch of dough that doesn't have that mother in it, and it doesn't have the same depth of flavor and also the pastries come out slightly differently—the edges are a bit sharper and it's not as refined a product. So for us adding the mother does add complexity of flavor and it rounds out and finishes the pastries in in the way I want it to.

So I started doing some research. I was using dough that was being made by the Lune pastry chefs daily to test my laminating techniques at home. And I eventually landed on the fact that maybe the problem wasn't my technique, maybe the problem was [that] the actual dough didn't have the extensibility it needed to be able to be worked with a rolling pin. So I started a deep dive into understanding preferments.

And I landed on poolish, which is the [preferment] with the highest hydration. And from the research that I had done, I understood that adding a poolish would increase the extensibility of the dough, making it easier for the home baker to roll it out with a rolling pin. And I'm like, “Okay, well, tomorrow morning, that's what I'm trying.” So I made the poolish, and then I made the dough from scratch with the poolish. And then the next day, when I pulled it out of the fridge, suddenly the dough was so much easier to roll out. Sometimes it's not that big a change, or a vast discovery, it can be just one thing that can totally flip something. And all of a sudden, the techniques that I'd tested with changing how the butter was laminated, were working, and everything was easier to roll out. And I got to the point where I was rolling up my final sheet of pastry, and it wasn't springing back like crazy. And I'm like, “Okay, so now I'm on to something.”

Andrew: The Lune cookbook calls for the use of clarified butter in the detrempe2, something I've never seen before. Why is that?

Okay, a Lune croissant is 43% butter, which is not normal, like a croissant normally contains about 25 to 33% butter based on how much you laminate in.

When I was figuring out the recipe for Lune like I'd only worked in the raw kitchen at Du Pain. And I had no idea how to prove and bake a croissant, I'd never even seen a proofed unbaked croissant before at the bakery. So I didn't even know what it should look like. And I did a bit of research and all the information was telling me was that you should prove your croissants for like, you know, two, two and a half hours at 28 to 30˚C [82 to 86˚F]. So, the first time I proofed and bake them, I followed that. And I remember pulling them out of the proofer and there was a little puddle of melted butter around it. And was like “Well, I'm not sure if that looks right or not because I've got no experience, but I'll bake it up.” And when I baked it up they looked really similar to what we've been baking at Du Pain and I'm like okay, "Well, that looks like a pretty good end product. But I don't think there should be a puddle of butter around a proven croissant."

So from then on, for about a week or so, I pulled the proving temperature back by half a degree every day. And I kept doing it until I pulled a croissant out of the proofer that looked like what I thought it should probably look like and I landed on a temperature where there was no puddle of melted butter around it and it was perfectly puffy. It almost looked like it was computer-generated.

So from then on, for about a week or so, I pulled the proving temperature back by half a degree every day. And I kept doing it until I pulled a croissant out of the proofer that looked like what I thought it should probably look like and I landed on a temperature where there was no puddle of melted butter around it and it was perfectly puffy. It almost looked like it was computer-generated. It wasn't time restricted, I just left it in the prover until I thought it looked like it might be ready to bake.

And I remember there's this transformation that happens where for good period of the proving time, it looks sweaty on the outside, and there are also these like little almost indistinct creases on the surface of it. When it looks like it was fully proven, that sweatiness disappears, the surface becomes almost matte, and the little creases in the shell disappear. It’s like it's filled out, it's now reached its potential. And I remember then baking it and getting this voluminous, glorious, finished product that was incredibly buttery, but not greasy at all, because the butter had remained solid during the proving process.

That's the difference between like a slightly greasy, doughy, flatter croissant, and [a] big beautiful voluminous one. [F]or me a croissant isn't just about the layers of dough and butter, [it’s] also about the space that's created between the layers of dough, and the more open you can get that honeycomb structure, the more it feels like you're eating like a cloud of butter and air.

When you put it in the hot oven, the shell that is created when it starts to bake locks the butter into it, so you retain more butter and get a more buttery product, but [one that is] less greasy. [The goal is to] put a croissant in the oven when the butter is still solid in the layers. Like obviously, there's the oven spring from the yeast. But the other way that you get the voluminous croissant is from the water molecules in the butter. When you first put it into a super hot oven, the water molecules create steam, and the steam pushes the layers apart as well. So that's the difference between like a slightly greasy, doughy, flatter croissant, and [a] big beautiful voluminous one. [F]or me a croissant isn't just about the layers of dough and butter, [it’s] about the space that's created between the layers of dough, and the more open you can get that honeycomb structure, the more it feels like you're eating like a cloud of butter and air.

For me, a croissant should be a celebration of butter, and I'm wanting to be able to replicate that for the home baker. But the more butter you laminate in the harder the pastry is to work. And adding clarified butter to the dough enriches the dough, it also means that it takes a little bit longer to prove because fat retards yeast, but the end product is a very buttery, more buttery than normal. And it also means you don't have to laminate as much in.

Andrew: So you're saying basically that that by clarifying the butter, you can use the an equivalent weight of butter in the dough, but you're actually adding more butterfat overall because there's none of the water in there.

Kate: [Yes.] Thank you for summarizing that for me.

Andrew: To me, really, the most important thing about this book is the technique. If you're a home baker who's interested in learning to make a croissant, I feel like this is the book. Like you said before, a book that has a section on croissants with 15 other types of recipes or whatever, it could be a good recipe, but this is the book for the person who really is ready to tackle this difficult thing.

I love that that's how you see the book because that's how I see it. My publishers have been asking if I've been thinking about a second book, and I'm not interested in writing a second book about croissants, because the thing that makes this book special is the technique. I could reel out 60 more recipes of what to do with it, but then that's just predictable. For me, the 60 recipes that follow the technique are not prescriptive—I want someone to buy this book and engage with it, so they can actually successfully achieve making croissant pastry at home. Because when you do achieve it, it's genuinely a big achievement, because it's not easy to do, and it's not easy to do well.

For me, the 60 recipes that follow the technique are not prescriptive—I want someone to buy this book and engage with it, so they can actually successfully achieve making croissant pastry at home. Because when you do achieve it, it's genuinely a big achievement, because it's not easy to do, and it's not easy to do well.

But when someone's done that, they might make two or three of the recipes that ensue in the book. But I don't want them to be prescriptive. I want I want people to feel like then. "Oh, so now I know how to make the raw pastry. I've got this idea that maybe I want to make a turkey and Brie croissant, or I want to do this with it." And all I want those 60 recipes to do is to inspire people to really think outside the box. "Now that I know that I can make the pastry, I can do whatever I want with it." For me, that first chunk of the book, the raw pastry and the shapes, that's the most important chapter in [it].

Andrew: The other thing I just wanted to talk about is the photography. While all of the images are beautiful, maybe my favorite part is the sort of slightly surreal fashion photography in it. And now, having spoken to you, I can only assume that that is your doing as well. So can you say more about how that came to be and what inspired it?

Since this book has been released, I haven't met someone that has understood what I wanted to achieve with this book more than you. And it's getting me really emotional.

The photographer that shot the book does all our work for Lune, he shoots all our monthly specials and stuff. And it's funny, he's worked with us now for over two years. Myself, Pete [Dillon, the photographer], the designer, and the stylist, we kind of had a bit of a chat about the shoot at the start. There's 60 recipes in the book, and [though] some have different garnishes and stuff, but they're all about the same size, and kind of the same color. And we were like, "How are we going to do that in an interesting way?"

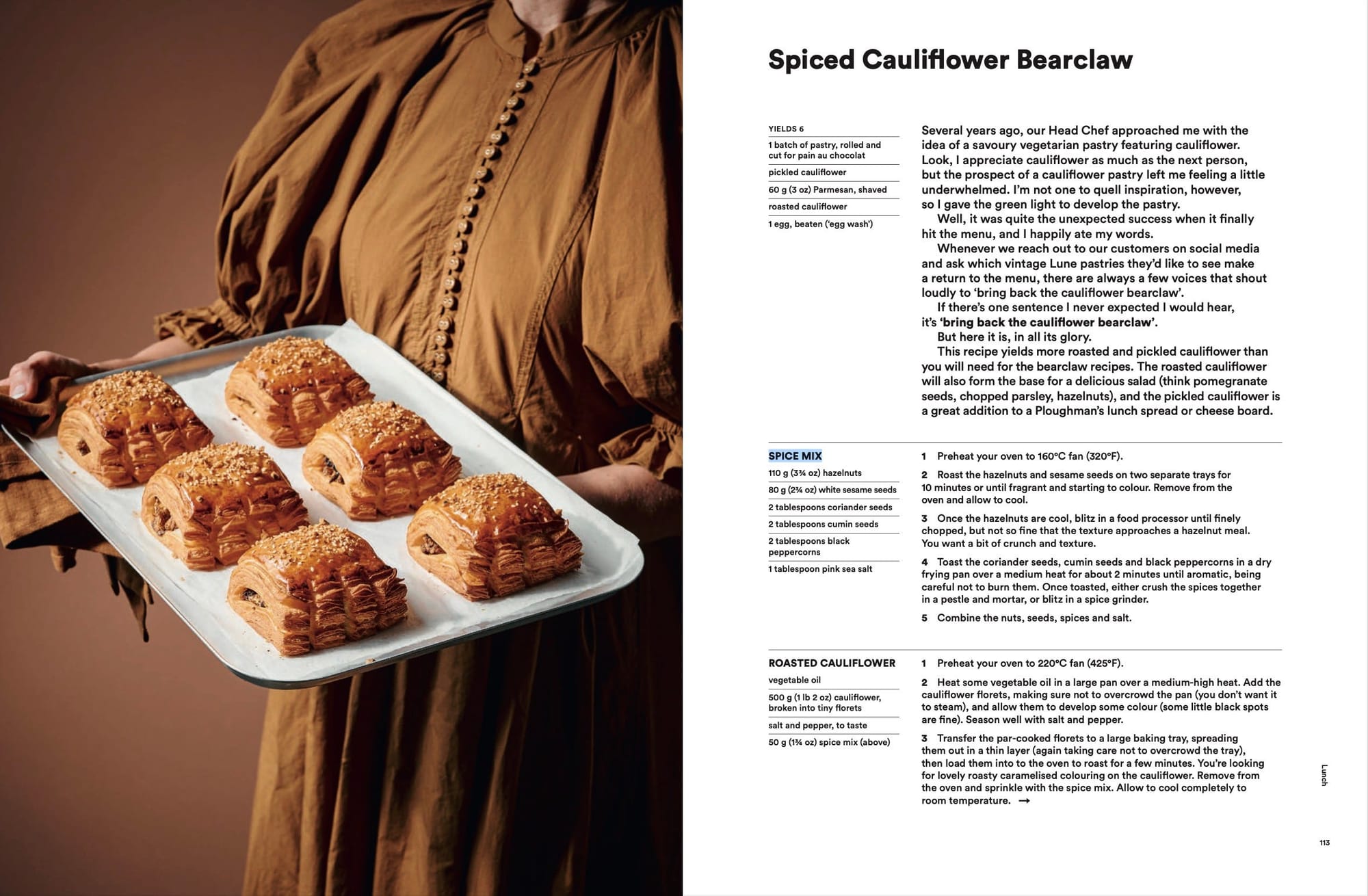

I wanted the book to be visually beautiful and I didn't want it to look like any other cookbook. I had I kind of had to stamp down on the stylist a bit 'cause she was, you know, loving her napkins and…A good example is the cauliflower bear claw, that photo of me wearing that dress that looks like it's someone from the prairie holding the tray. I mean, I would never wear that dress, but I love that photo so much, because when Pete was taking that photo, he's like, "Kate, you're standing up so straight." And I'm like, "I've got six children and I live on the prairie and I'm really proud of the cauliflower bear claws I just pulled out of the oven!"

But the first time we shot that recipe, it was on a pink tablecloth with a few cauliflower leaves and a couple of glasses of white wine. And I'm like, "What's this? No one's sitting down to lunch, having a glass of wine and a cauliflower bear claw with cauliflower leaves. I hate this, it's classic food styling and I'm not interested in it."

So we decided that a way to make each photo really unique was to feature some local fashion labels, in particular labels that I buy from that I have an affinity to, like the photo of the reuben croissant. (That's actually my dog, Lily. And the book is dedicated to her because, like because we were in a pandemic, and I live alone with my dog. Like she just sat at my feet for the entire time I wrote the book. So who else could it be dedicated to?) And the photo of the plum Danish, I'm an ambassador for Porsche and Pete, the photographer, said, “Hey, the current car that you're driving has plum colored leather seats. Let's shoot the plum Danish in your car."

So it was it was the most fun photoshoot. For every pastry, we just really thought like, "Let's think outside the box and do something really cool and different." And it was really collaborative. I was sad when the photoshoot was over, too. I loved that.

Andrew: I have a lot of favorite images from the book, but I think [the one of you sitting on the crate] is my favorite favorite.

That is a cheeky photo! You know what, it might be one of my favorites as well. We tried a few other things. And then there was a crate that I'd been standing on. And we talked about me holding the cruffin and a chocolate milk. The food stylist had gone to buy chocolate milk and I just sat down on the crate to check my messages. And then the designer said, “Don't move!” And she put the cruffin on the crate behind me, and she's like, "Pete shoot that, that's really cool." [I responded,] "No, you're not taking a photo off my ass." He's like, "Yeah, we should do this. It's really funny."

My editor said to me at the very start, first and foremost, a cookbook is educational, and it's teaching people something but it doesn't have to be boring like a textbook, it should reflect your personality.

Images shared with permission from Lune, by Kate Reid, photos by Pete Dillon, published by Hardie Grant Books, February 2023.

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.