Ground Up Grain

Valley Malt's little sister

Table of Contents

Ground Up Grain mills fresh flour mill in Holyoke, Massachusetts, and is a sister enterprise of Valley Malt, the first malthouse in New England in more than a century. These businesses are the undertakings of Andrea and Christian Stanley, who launched Valley Malt in 2010, and Ground Up Grain in 2019.

The couple, who were avid home brewers, got curious about grain when Hungry Ghost Bread got their customers to grow patches of wheat on their front lawns. While the Pioneer Valley—the more common name of the fertile Connecticut River Valley— was once the breadbasket of New England, by the early 1900s, grain growing and handling had consolidated in America’s grain belts.

However, farmland in this part of Western Massachusetts is so good that agriculture didn’t vanish. Any fall apple-picking foray in the area reveals the slatted sides of tobacco barns, which are ventilated for proper drying. Tobacco, dairy, and vegetable farming maintained a good foothold, even as the Five Colleges came to co-dominate the landscape. By the early 2000s, the local food movement was firmly established, and Andrea and Christian were excited to find a role for themselves in that work.

Initially, they thought they could start a brewery that used locally grown barley. They soon learned that malting is an essential step in preparing brewing grains, and that the nearest malthouse was in Wisconsin; the smallest batch this company could malt was far beyond what the farmers near them were growing. Malting and brewing were once part of household work, but as America urbanized, those tasks industrialized, and even in the early 20th century, many breweries had their own malthouses. If any malting equipment was mothballed in abandoned warehouses, it would take considerable effort to get it up and running.

Luckily, Christian is an engineer, and he designed a countertop malting system. As they geared up to open a business, he used his skills to kit out their first operation. His knowledge, and ability to look at systems in any given manufacturing setting and see what needed to physically happen, was key to making small-scale malting happen. In my mind, Andrea has a parallel set of equally crucial skills: I think of her as a social engineer, someone who can see a situation’s big picture and coordinate the essential aspects, the people and moving pieces and parts, to make it happen. Andrea studied the histories and contemporary practices of malting and grain, and envisioned how to recreate a local malthouse. I marvel at this combined set of talents and what the two of them have achieved so far.

As a flour hound exploring the people reviving regional grain systems, I met Andrea early on in my wanderings. She introduced me to malt, and I smelled Grape Nuts! After my first visit to their malthouse I made my take on the cereal, which is really just a batter that is baked, crumbled, and baked again. I also added malt to my pancakes, and wowie, they went through the roof. Malting is the process of soaking grains to make them sprout, and unlock their enzymes so that the carbohydrates in the kernels are more accessible to the fermentation process in brewing. Bakers use malt for sweetness, and sometimes, to tap into that enzymatic busyness; more often, however, to control bread fermentation, barley malt is non-diastatic, aka, not active.

More importantly than helping me amp up my pancakes, though, Andrea burnt a primary concept in my brain: She emphasized the importance of human connection, and conversations as a way to create change. I had this idea that agricultural change would strike like a lightning bolt, and suddenly mills and malthouses would dot the landscape again. But Andrea helped me see that change is more incremental, person to person. Change travels from ear to ear, as we listen to each other and think about what is and what can be.

This is how she built relationships along the nonexistent supply chain, talking to farmers who were growing grains locally and regionally, and developing an appetite for this novel ingredient in craft brewers. Pretty quickly after Valley Malt began, interest in craft malting swelled across the country. People were psyched to kickstart malthouses, and Andrea saw a need for a formal way to share information on the endeavor. She started the Farmer Brewer Winter Weekend to help answer the many questions that farmers, brewers, and would-be maltsters were asking. Similarly, she started the Craft Maltster Guild.

While spiderwebbing connections to help support grains in general, Valley Malt was also growing. They upgraded their one-ton malting system to a four-ton system in 2012, building the malthouse into their garage. Soon, demand eclipsed that setup, but they didn’t expand for quite some time. Their home and malthouse overlooked vegetable fields, and in addition to using grain from local farmers, they farmed grains themselves. Andrea’s test plots of barley stretched out to collaborations with farmers and university plant breeders across the country, everyone investigating what types of barley would be good for farmers, good to malt, and good for brewers.

As you can see, they were all grains, all the time, so making flour was almost inevitable. In 2018, Hungry Ghost asked Andrea and Christian to mill flour, as the farm which had been doing so was stopping its grain operations. This circle—from Hungry Ghost sparking their interest in malting to Hungry Ghost sparking their entrance into milling—coincided with plans to move the malthouse to Holyoke, a former mill town with considerable hydropower resources—and plenty of vacant buildings to repurpose.

When Massachusetts created the Food Security Infrastructure Grant (FSIG) program, it seemed tailor-made for creating a grain center in Holyoke and make a place to aggregate their operations. Valley Malt and Ground Up Grain received a $500,000 grant to establish a grain hub, and build storage, cleaning, and handling systems for regionally grown grain. More recently, Ground Up received another FSIG to make an onsite bakery and support value-added operations. Housing all these enterprises together makes sense, to take advantage of the grain knowledge and relationships that the Stanleys have accumulated, and to assemble key grain handling infrastructure such as silos and cleaning systems, plus value added facilities that are critical to expanding opportunities in grains.

(Value-added is a term often used in agriculture and refers to taking a raw ingredient or material and adding value to it; the idea is that farmers and small-scale processors can capture more of the value of the basic element of a food, fiber, or beverage product, rather than transferring the bulk of an ingredient’s worth to buyers.)

I caught up with Andrea Stanley by television-phone in February to help introduce flour fans at Wordloaf to this dynamic operation.

Amy Halloran: How did Ground Up start?

Andrea Stanley: Well, Jonathan Stevens from the Hungry Ghost came to our field day in 2018. We would invite all the breweries that we work with to visit in the summer when we were still doing some farming ourselves. They brought beer, and we’d have food, and walk around because we always have at least a few fields right around our house. I think you’ve been to at least one of them.

AH: Oh yes! (I can remember walking through the green and goldening barley in a single file, Christian at the front, and a bunch of grainiacs touching the grainheads and stalks. That kind of experience makes an impression.)

AH: Jonathon bought a bag of malt for the bakery from us every couple months, and so he came to this field day and met some of the farmers that we worked with. He just approached us, either that day or shortly thereafter, and said that Four-Star Farm was not going to be milling anymore, and would we be interested in putting in a mill. He pointed us in the direction of New American Stone Mills, which had just made a 48-inch mill for One Mighty Mill. Knowing what we know about malting, we knew we might as well start with a bigger piece of equipment than you think you need because you're going to need it soon.

In the meantime, we were talking with Ben Roesch (from Wormtown Brewery). Ben was kind of looking to do something more of his own on the side. And so, he became a partner with us, and he worked on getting Birch Tree Bread Company as our second customer, Hungry Ghost being the first. We ordered the mill in December, and we got it in March of 2019. We had put it on the second floor of the building, so it was a process. We had to take a crane and lift it up and bring it in. And that was pretty exciting. And then, yeah, then we just started milling. I mean, it was just kind of like, OK, turn it on.

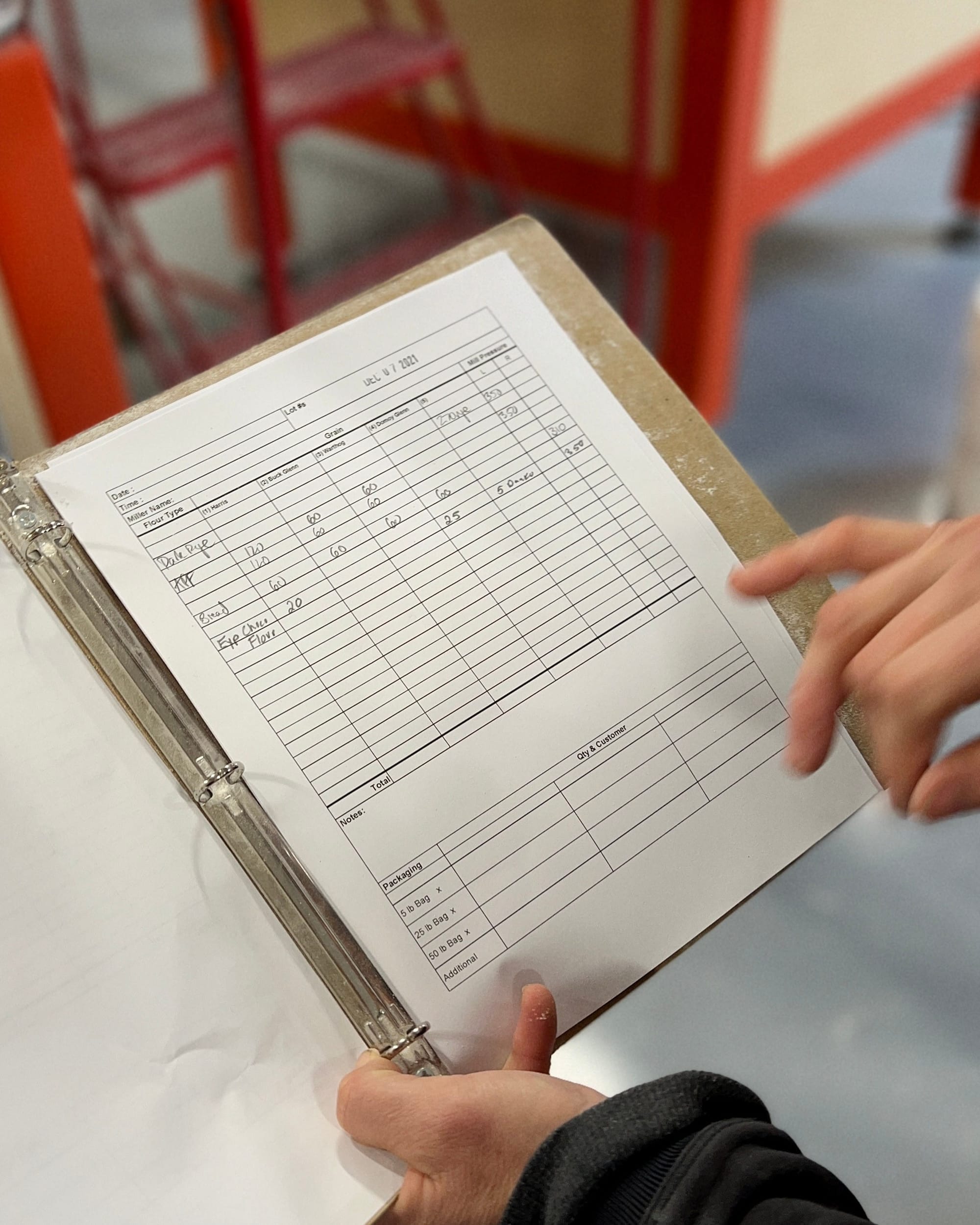

The grain side of things was in our wheelhouse. We knew what kind of grain we wanted to use and how we wanted to create blends, rather than just having single varietals. We went in a very similar direction to where we evolved with Valley Malt. We didn't want to do a lot of niche things, and have you know, 10 different types of corn or wheat. We wanted to make a bread flour and all-purpose flour, a pastry flour. We knew we wanted to highlight Danko rye because that was always a really lovely grain variety to work with. Because Jonathan told us what he wanted in flour, we knew that we wanted it to be sifted. He sent us diagrams of these French style bolters that he was interested in, and it just so happened that at the time Andrew was starting to make those (at New American Stone Mill).

AH: So, you were the first miller?

AS: Yes. We didn't hire anybody until 2020. For the first year, it was just me, Christian, and Ben. Basically, we were just milling for Hungry Ghost, which was maybe 5 to 600 pounds a week and a little bit for Birch Tree. And then COVID hit, and things went bonkers. We were milling 15 hours a day to meet all this demand, and Ben’s life changed. Staff were furloughed at Wormtown and that was his priority. So, we bought Ben out of his share and told him he can have free flour for life. It was very, very important for us to all maintain our friendship. Had COVID not happened, Ben would probably still be a partner in the flour mill, but that was a crazy time.

Jonathan was like a partner at the beginning, too, testing out the flour, and he was willing to be our salesperson. He did not have the time to do so, but he was willing to. He was invested in our success. And that mattered.

AH: How many people are working at the mill now?

AS: We have three full-time people working in the mill now. Tyler is our mill manager. He was one of the last people we saw before COVID hit, on a tour with UMass bakery —he worked in the college’s sustainability department. When he got furloughed from UMass, he reached out to us and asked if he could volunteer and we said, well we don't really want volunteers, but we could pay you. He went from being our only employee at the mill to now managing two other mill staff. He’s managing a more complicated operation, one with more products, and retail instead of just wholesale. There's a whole e-commerce component to the business, which is pretty important for our profitability and for our general direct-to-consumer relationships. When I think about the e-commerce component, we probably have four people working at the mill because we do have other staff that help with fulfilling orders.

And then the mill had its own little sister, the bakery. This year we put in a pasta shop and a bakery, so we're now making pasta, and that's really exciting, to have another grain-related product that we're processing. It’s basically just water and flour, and the machine looks like a Play-Doh factory.

AH: That's so fun. Is there a learning curve to making pasta?

AS: Well, I just opened up the owner’s manual and started pushing buttons on Sunday. (We spoke on a Wednesday, which happened to be Valentine’s Day, perfect for my true love of grains!) And I've probably made about 100 lbs. of pasta already. I played around with all the different dyes that we have. I’ve been doing a lot of single-variety pastas to get a sense of the color and the flavor and the texture profile for each one, so we can start letting people taste it and decide what a good product might be.

Gabriel Key, owner of Foggy Mountain Pasta in Virginia is coming to do a whole day training on making pasta from fresh flour with our particular equipment. He used to buy flour from us for his pasta, but then he got a New American mill. He's got years of experience using the machine and fresh flour, so we’ll definitely be more up to speed.

AH: How did you figure out how to equip the bakery?

AS: We hired Aditya Sastri from Steel and Rye to be our consultant for outfitting the bakery because we don’t know that equipment. We had thoughts about not sizing it too small, but also not sizing it too big either, based on our other experiences. Because the difference between something that has an output of 30 lbs./hour and something that makes 100 lbs./hour might not be that big of a cost.

We plan on having guest speakers come in and teach some classes, but we don’t have a business plan to start a bakery yet. That’s a whole other thing, to be able to afford a head baker and make that happen.

AH: How do you plan on selling the pasta?

AS: That’s going to grocery stores, little shops. We have the Survival Center. (Food pantries in MA are part of entities called survival centers.) They have an amazing program in Massachusetts where the state has farm to pantry grants to support local food.

AH: The flour is already with Smith College Dining Hall, right?

AS: Yes. We're just going to start sending fresh pasta everywhere. I've got pallets of malt going out today that will include some fresh pasta, just to see who's interested. If I send pasta to brewery, they might want to start putting our pasta on their shelves at the tap room, just like we've done with our retail bags of flour with some of our bakery customers. If somebody's in a bakery and they're buying bread, then they can pick up a box of pasta too.

AH: How are you drying the pasta?

AS: We have a huge dryer, it's basically like a kiln. It looks like a shed you'd have in your backyard.

AH: Let’s try to help people picture the grain flow in Holyoke. Is the grain specific to the mill? Do you have segregated storage spaces?

AS: Yes and no. The Warthog and the Harris white wheat, and the Danko rye are all used between Valley Malt and Ground Up. For the most part, we're just pulling off the same silo. The hard red spring wheat that we use is not used in the malthouse at all. So that's a grain that is unique to the mill. But the grain procurement and the grain handling and management, that is something the two businesses share.

I think a lot about how to run a business like ours, such a small and kind of young and undercapitalized, under-resourced place. We decided to add the flour mill and now we're diversifying into more value added. But I think all those decisions—it's like thinking about your kids. Like, did I give Felix enough attention? But then what about Franny? (These are my kids!) At this point in the game, I have this mental wrestling match with what to focus on. I still think of myself as a maltster. That is where my head goes. I go into work with my maltster cap on, and I love it to this day, like I would do it all on its own. And yet, I really, really love Ground Up as well, and see all the right reasons why we did it and why we continue to do it. I like the fact that I can use what I know about the grains to help me develop the pasta. I think it helps me immensely to think of flour as a product from a grain, not just as an ingredient for pasta.

And I’m excited about more than malting and milling, but also nixtamalization and sprouting. Yesterday I did a run of 100% Harris wheat pasta, one from regular Harris flour and one from sprouted Harris flour. Who gets to do that? Me!

I think that there's a lot of innovation in our future. Being able to do the value add to the milling and the malting through the pasta—that makes me wonder what other things could be on the horizon.

To follow that future, keep in touch with Ground Up!

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.