Friday Bread Basket 7/21/23

Welcome to the Wordloaf Friday Bread Basket, a weekly roundup of links and items relating to bread, baking, and grain. Just a reminder, this will be the last FBB before Wordloaf goes on summer break next week.

Counting sheep bakers

I loved this post from Kimberly Coburn’s What Kind of Magpie, When your demons come, feed them bread, and not only because it includes a nod to Wordloaf as a source of good bread intel at the end. Kimberly describes a novel way to deal with the agonies of insomnia by thinking of all of the bakers that are also wide awake at that hour:

But, lo! I may have stumbled upon an unexpected solution. Not to the waking part—that is probably a multifactorial situation that no doubt has to do with fewer hours on screens and more time touching grass. No, this is really more of a little thought detour once you’re already awake, an offramp from the fretful highway that sees the most traffic in those pre-dawn hours.

Bakers.

I recently overheard someone mention that when he can’t sleep in that lacuna between night and morning, he thinks about bakers. Bakers begin their days during those restless hours that plague so many of us. While I toss and turn, somewhere in my area code, a baker sips a cup of strong coffee, twists pastries, scores pillows of sourdough. There, the air is not heavy with dread but oven-warmed and dusted with flour.

There’s something supremely comforting in knowing that out in the darkness before sunrise, aproned angels are performing mundane miracles. While my hands tug impatiently at the bedclothes, theirs are steadily stirring, stretching, kneading: the most ancient gestures of nourishment. I wouldn’t be shocked to find out that they leaven the dawn’s color into the sky.

The post includes passages from classic literature on the “witching hour,” from Shakespeare to Ray Bradbury.

Run from the borders

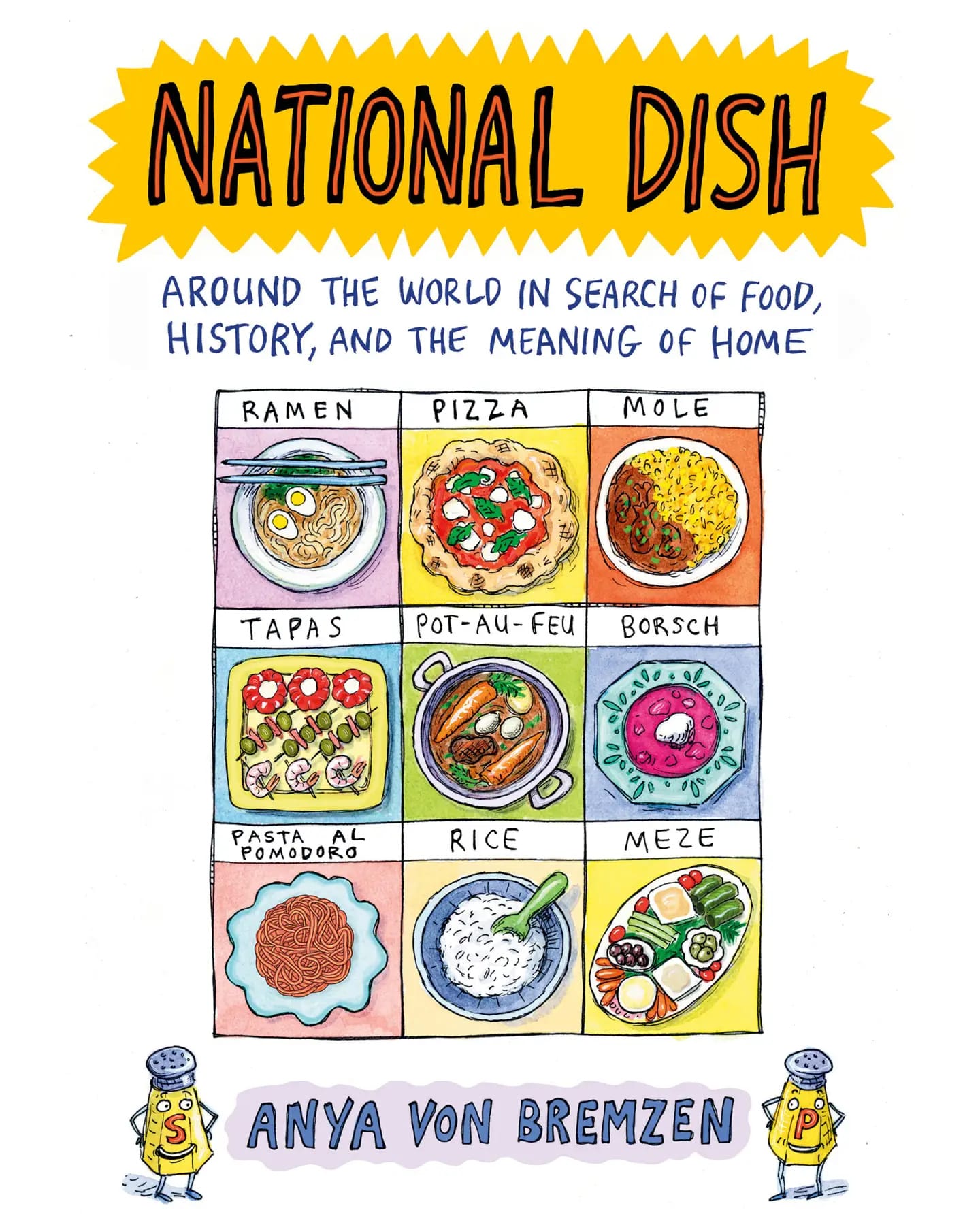

Saveur Magazine published a great discussion between Ben Kemper and Anya von Bremzen, all about her new book, National Dish, which explores the complicated and thorny questions around whether a food “belongs” to any particular nationality:

Did researching this book change your view on cultural appropriation as it relates to food?

When we talk about cultural appropriation, we’re really talking about racial injustice and other power imbalances. I think it would be much more useful to talk about those issues directly. So, instead of “he appropriated my mofongo,” maybe it’s, “there is racial injustice in the food sector.” National identities change all the time. When most dishes were invented, current borders didn’t exist—so how can you really claim something is from Syria or Lebanon or Turkey when it was eaten under the Ottoman Empire? The philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah says that when you treat culture like corporate property that belongs to someone, you’re not acknowledging the fluidity and complexity of cultural exchange. Nations do that with food. I wish every time we talked vaguely about cultural appropriation, there was a “donate” button, because ultimately only political action can effect change.

In the book, there’s constant tension between universality and propriety. That a dish like pizza can be eaten everywhere, with new iterations being created all the time, and yet many claim it’s from a specific place. How do you walk that tightrope?

After writing this book, I’m much more in the universalist camp. When you start reading about this stuff, you see how recent borders are, and how histories are appropriated and mythologized for the purpose of commercial and political interests. But regardless of the actual history of a dish, what’s more important is how people feel about it.

Tomayo, tomayo

Eric Kim wrote about the joys of the tomato sandwich for the NYT Magazine, of which it is now high season. (Or about to be high season; where I am, the good farmer market tomatoes haven’t yet materialized.) Eric is from the South, where the tomato sandwich is a thing of special importance:

When it comes to the tomato sandwich, at least in the South, the conversation is less about what it is than what it is not. According to the readers of my hometown’s Gwinnett Magazine in Georgia, the Official Tomato Sandwich is two slices of white bread (“Not toasted. Fresh, so it sticks to the back of your teeth”); a homegrown vine-ripe tomato (“Not peeled. Juicy so you have to hold it over the sink”); black pepper and salt; and “a sizable portion” of mayonnaise (“Not Miracle Whip”).

Central to all this is good timing. A homegrown, vine-ripe tomato is ready when it’s ready. That restless buildup for the perfect tomato to slacken and blush, to actually smell of fire and rain? Some people wait all year for it. Your tomato need not be plucked from the Garden of Eden to be good: Just try to find one that came from a farmer during its high season and not a big-box supermarket in winter. Though cherry, Campari and other small greenhouse tomatoes can be lovely, what you really want is a big, peak-season beefsteak or heirloom that still has the warmth of the sun as you slice into it.

Earlier this summer, Mary eagerly turned a small German queen tomato — the only one to successfully come out of her garden so far this year — into a sandwich. What else would she have done? “The tomato was good,” she says. “The mayonnaise was good. But the bread was not great.” That’s because she didn’t have her Merita Old Fashioned Bread, the soft white sandwich loaf she was used to. (Her family didn’t have a lot of money when she was growing up, she says, so her mother would go to the bakery thrift store where bags of bread, especially Merita brand, were sold closer to their expiration dates.) You could use a fancier sourdough or a crusty focaccia, but why? The joy of a Southern tomato sandwich is to highlight the fruit. The mushy whiteness of a soft sandwich bread, as the dripping tomato sogs the edges, is auxiliary for some.

I love tomato sandwiches, though I am agnostic about the bread you use: both soft white and crusty breads work beautifully (though in the case of the latter, I think open-faced is the way to go). Mayo, however, is non-negotiable IMO.

That’s it for this week’s bread basket. Have a nice weekend, see you all on Monday.

—Andrew

Member discussion