Friday Bread Basket 11/4/22

Homer Simpson: I’d like the phone book for Hokkaido, Japan.

Librarian: There you go, the phone book for Hokkaido, Japan.

Homer: I would also like to borrow your phone.

Librarian: Is it for a local call?

Homer: Yeeeeaaassssss………..

Welcome to the Wordloaf Friday Bread Basket, a weekly roundup of links and items relating to bread, baking, and grain. It’s mostly sandwiches and dumplings today.

The milk bread of human kindness

While I was writing up my shokupain de mie recipe, I stumbled upon this really interesting discussion of the origins behind the various names that milk bread and shokupan gets given, from a mysterious Substacker who goes by the name of JAQ:

Shokupan (食パン) is a Japanese term that can literally be translated as ‘food bread’. It is a broad category that refers to a basic sandwich bread that can be sliced into neat squares—somewhat of an analogue of Western sandwich bread, though fans of shokupan note that it is usually softer and richer as it often includes dairy and a water roux method during the production process. But the sheer variety of breads ‘shokupan’ encompasses makes it difficult to be narrowed down, which is why it can come with an infinite amount of modifiers: it can be mass produced or artisanal (高級食パン=luxury shokupan), contain no dairy or lots of it (牛乳食パン=milk shokupan), come with inclusions in the dough or a filling (あん食パン=red bean shokupan), or even in a domed shape (called 山食 or mountain shoku[pan]).

Read the whole thing here:

The sandwich channel

Taste shared a profile of Barry Enderwick, aka @sandwichesofhistory on TikTok and Instagram, a chronicler of the world’s most interesting and obscure sandwiches:

Barry Enderwick is a middle-aged guy who has made himself into one of the more unlikely—and extremely watchable—micro-stars of the food content omnishambles of today’s social media. As a lover of food media, you have likely been served one or more of his accounts, the most popular being @sandwichesofhistory, with its nearly 300,000 TikTok followers and its 100,000 followers and counting on Instagram.

In similarly themed videos posted on a daily basis, Enderwick re-creates sandwiches that have been lost in time—like the Cottage Cheese and Egg sandwich (1941), the Banana, Lettuce, and Anchovy sandwich (1924), and the Bran Sandwich (1936). He scours arcane sandwich texts (cookbooks, newspaper articles, and the depths of searchable culinary history), translating their coolness and weirdness for a large audience of sandwich lovers. “The really good sandwiches and the really bad sandwiches are the ones that get people really excited,” he tells me, but you can see it for yourself on these accounts, with each post accompanied by hundreds and hundreds of comments, from friend tags to deeply personal memories to endless rows of response emojis ranging from fire to bacon to poop.

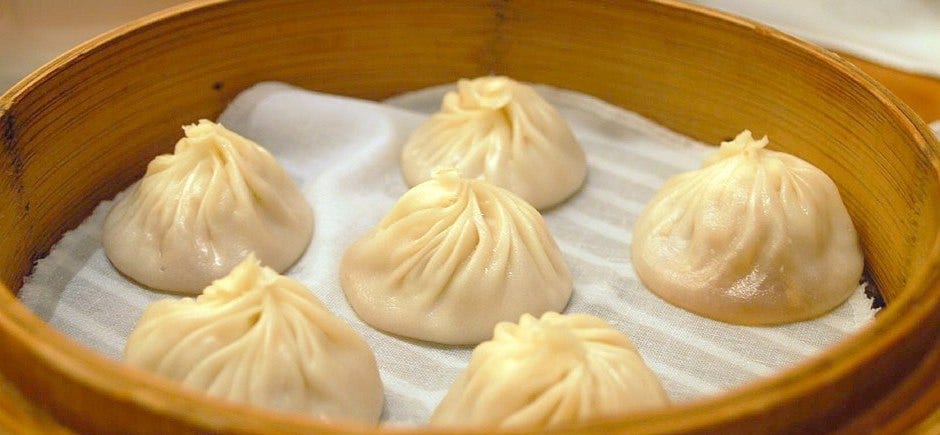

The universal language of dumplings

Toronto food writer Karon Liu edited a new book of essays all about dumplings, called What We Talk about When We Talk about Dumplings, which I cannot wait to read. Over at LitHub, he shared an essay all about how the book came to be:

The more I write about food, the more I come to realize that such an undertaking requires a team of people. Yes, dumplings are universal—it’s why they’re such an easy entryway into a culture’s cuisine. At the same time, there are so many dumpling variations: steamed, fried, or boiled; filled or not; sweet or savory; big or small; in soups or on their own. There are nuances to cuisines that vary between regions, cities, and—heck—households and generations that no one person can ever fully grasp.

Technically, the matzo balls in Ashkenazi Jewish cooking, the xiaolongbao or soup dumplings in Shanghainese cuisine, and Jamaican spinners used in soups and stews are all categorized as dumplings. But there’s not a lot else these dishes have in common—aside from their deliciousness. I remember being introduced to spätzle as a teen, when I was invited to a friend’s home to try Austrian home cooking. I gobbled the spätzle along with the schnitzel, perplexed but mind-blown that dumplings existed beyond the wontons I ate growing up.

Heck, even with the wontons, everyone in my friends’ and family’s circles prefers a different filling or fold. One friend prefers the squeeze method—literally putting a bit of filling into the wrapper and then squeezing her hand into a fist to seal it—because that’s the fastest method (and most common among sifus at restaurants). My mom, meanwhile, prefers the fold that makes the dumpling look like a person wearing a bonnet ’cause that’s what her mom taught her. Don’t even get me started on the differences between a wonton, a water dumpling, a potsticker, and a soup dumpling…mostly because I’m still learning the different techniques and regional variations of each of these as I dive ever deeper into Chinese cooking.

That’s it for this week’s bread basket. I hope you all have a peaceful weekend, see you on Monday.

—Andrew

Member discussion