Friday Bread Basket 10/6/23

Hello from the Wordloaf Friday Bread Basket, a weekly roundup of links and items relating to bread, baking, and grain. Pictured above is one of the mooncakes I bought in Boston’s Chinatown the other day, that one filled with winter melon paste.

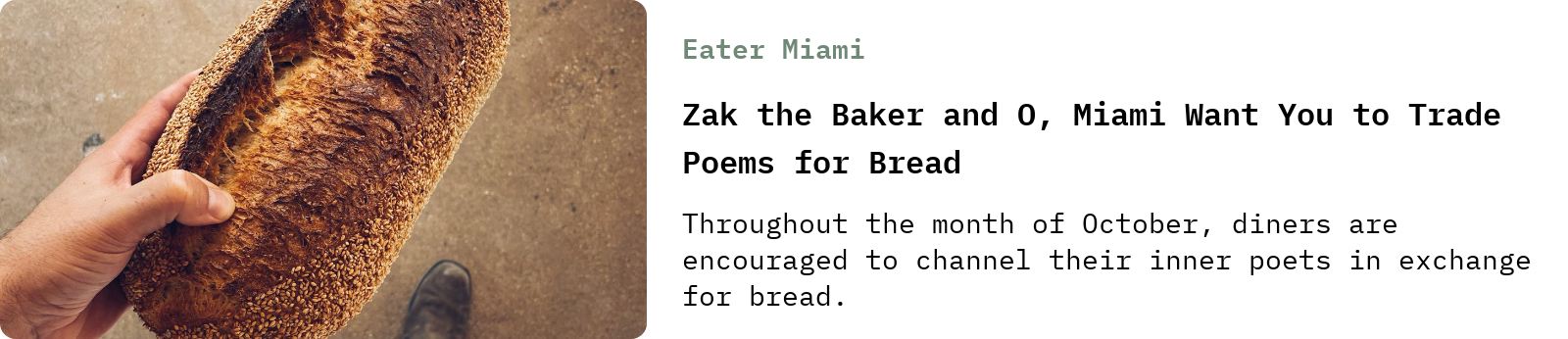

Baking for poets

All this October, Miami’s Zack the Baker is giving away free loaves of bread in exchange for original poems about the city’s food:

Stern says the reasoning behind the theme of “Miami food” is to help create a conversation about how food is the connecting thread that runs through our different cultures and experiences. “The idea is to get people thinking Miami can have its own unique regional cuisine. We have incredible agriculture here if we allow ourselves to celebrate and be proud of it.”

For Stern, food culture is influenced by agriculture, politics, religion, immigration, the economy, and industry. He uses his bake shop as an example, where Stern substitutes local mangos and bananas for traditional ingredients like apples and apricots. “We are a traditional kosher bakery in 2023 when Miami is surrounded by Caribbean and Latino cultures and flavors. It’s a time when the Jewish community is different from the 1960s and 1970s. We bake and use kosher rules, but we also look to see what’s growing and allow the community's flavors to come in. And that’s how you get a unique food culture.”

German engineering

Wordloaf fave Nicola Miller wrote about GBBO competitor Jürgen Krauss’s new cookbook, German Baking, and the “charm” of baking competition television on her newsletter Tales From Topographic Kitchens:

Jürgen has said that when it came to each week’s bakes, he started with the story he wanted to tell rather than the cake itself. There would be no design for design’s sake. From my perspective, there appeared to be two intentions that guided his time on the show: the acquisition of new skills via baking challenges that would take him out of his comfort zone, and the championing of German baking in a relatable way. From my perspective, underpinning this all was the Jürgen who immigrated to the UK all those years ago, yearned for the food he grew up with and learned how to bake them, making do with whatever was to hand, ingredient-wise. As Jürgen progressed through the show, his conformity to habit and recipes appeared to lessen as he gained new skills and experience and had to cook from deliberately incomplete recipes. His confidence in himself as a representative of heritage German baking became evident as he slowly told his story through food. His success at the latter should not be underestimated in the face of a particular male judge who once went to Germany and probably feels himself to be an ‘expert’ on German baking as a result. We all know what tends to happen when contestants tell this judge about the baking they are deeply familiar with.

I’ve never seen GBBO, but I am definitely ordering this book.

Rugalach rats

For Vittles’ British Jewish Food Week, Adrienne Katz-Kennedy gives a thorough roundup of London’s rich rugelach scene:

Take rugelach, for instance. The name rugelach comes from Yiddish, meaning ‘little twists’ or ‘rolled things’, referring to its shape. Its origins stem from a combination of Eastern European communities and pastries (kifli, kipferl, rogal, rogaliki…), all of which are small, crescent-shaped and, most often, laminated. Rugelach in the US, like a good portion of the American food system, exists because of the World Wars, the Great Depression and the rise of convenience foods that emerged from them. The yeast once present in rugelach was removed to save time and reduce the cost of labour, while cream cheese was added only because of the influence of Philadelphia post-Depression. (This is a staggering example of how powerful marketing can be – it managed to insert dairy into the cuisine of a culture prone to lactose intolerance.)

Yet rugelach in the UK is a different thing entirely. Across London there are nuances that depend on the bakery’s community, as well as the personal history of the individual baker. The most commonly found fillings are chocolate, cinnamon and vanilla, while most bakeries produce a yeast-enhanced, laminated dough, like the original Eastern Europe variations. The word ‘rugelach’ can sometimes mean different things in different bakeries: in some it signifies a shape and filling but can be as large as a croissant; in others, ordering ‘rugelach’ can simply refer to any miniature-sized pastry. Some bakeries offer ‘flaky rugelach’ made from unyeasted dough which is then rolled into spirals with fruit fillings. At others, the rugelach are so dense and squidgy with chocolate you’ll wonder if there’s any dough at all.

(This post is paywalled, sorry, but Vittles is a newsletter you really ought to subscribe to. I haven’t visited London in decades, but I still consider it essential writing about food and culture.)

Stray Crumbs:

- You’ll see yours truly in ‘s recent post about the first week of her book tour. I was so pleased to meet a bunch of other Wordloaf subscribers at the event:

That’s it for this week’s bread basket. Have a peaceful weekend, see you all on Monday.

—Andrew

Member discussion