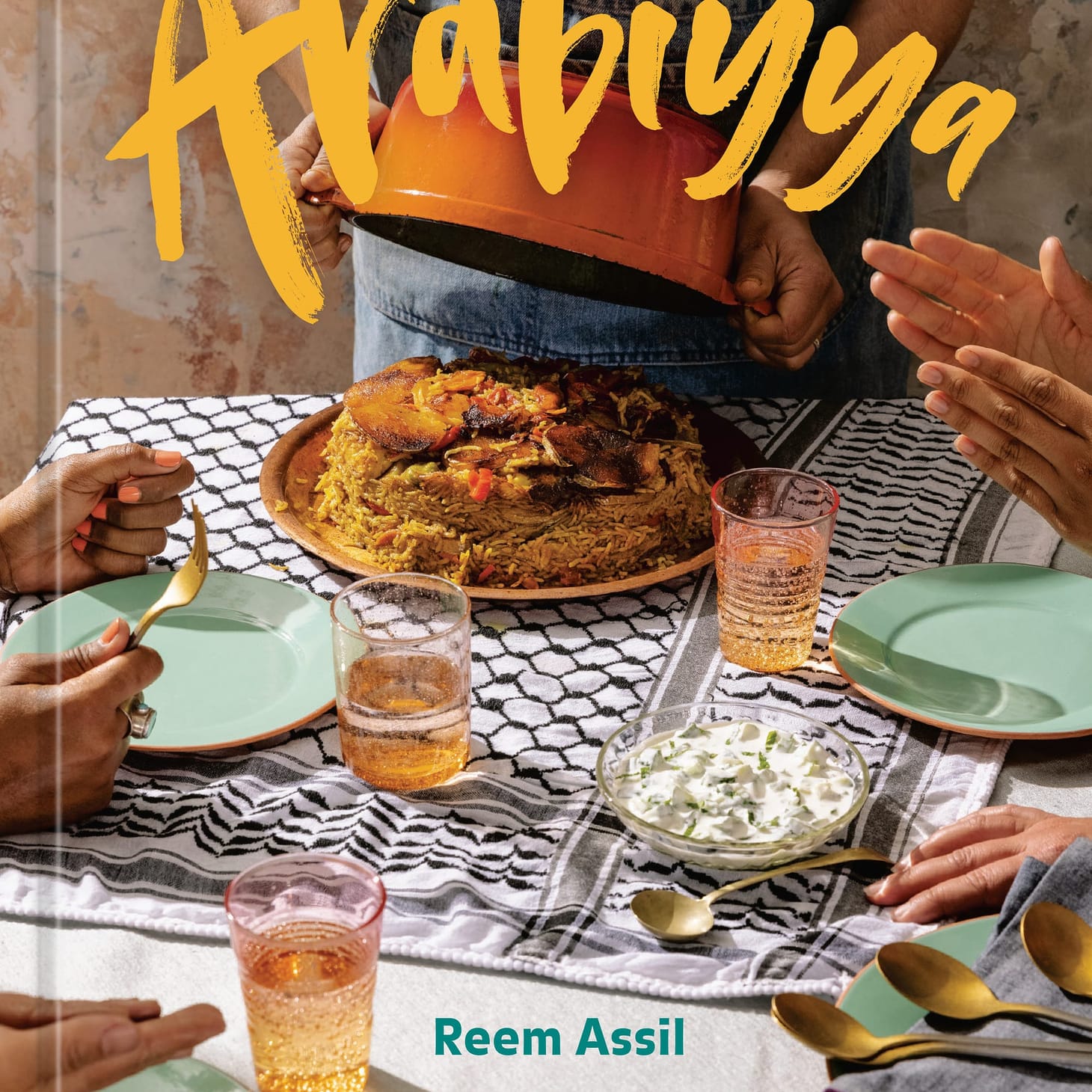

Book excerpt: Reem Assil's 'Arabiyya'

For the Love of Bread

Table of Contents

This week we have a special treat: An excerpt and a stack of recipes from Reem Assil’s new book Arabiyya: Recipes from the Life of an Arab in Diaspora. Reem Assil is a Palestinian-Syrian chef based in Oakland, CA, and the owner of Reem’s California, a nationally acclaimed restaurant, inspired by her passion for Arab street corner bakeries and the vibrant communities that surround them. She is also a fierce advocate for social justice and the rights of workers, her own or otherwise:

I did not start Reem’s to own a restaurant but rather to build a transformative space, where everyone has a voice; for my employees, my customers, my community, and, not least of all, for myself. I did it to build a strong, resilient community, using the foods of my heritage as a tool. On a perfect day, I would walk through my kitchen and see Nino, who could only speak Tagalog when he first joined Reem’s, patiently teaching Angela, newly arrived from El Salvador with no kitchen experience, solid knife skills. I would taste Mariana’s Oaxacan mole, prepared for a staff meal, and see her face light up at my suggestion that one day, she, too, could have her own restaurant. I would hear Armando’s hysterical laugh from the back as he danced to cumbia while doing the day’s inventory. Reem’s is made up of all of my team members’ rich experience and knowledge. Their talent and dedication are the real secrets behind our success; they are the very heart of Reem’s.

(The above quote is also from the new book, as excerpted in the SF Chronicle earlier this week.)

I love this book, and am so excited to share pieces of it here. Not do we get a long, beautiful essay about Reem’s journey to becoming a baker, but it comes with a cluster of recipes for making one of my favorite flatbreads, man’oushe, the za’atar- or cheese-topped bread that rivals pizza in its deliciousness.

I hope these excerpts encourage you to run out and buy a copy of Arabiyya yourself, I promise you will not be disappointed.

—Andrew

THE BASICS OF BREAD MAKING

My earliest memory of bread was not the Arab bread of my mother and father’s childhoods but rather of a yeasty sweetness wafting out of the smokestacks from the Wonder Bread factory we used to pass driving from our home in Sudbury, Massachusetts, to the Natick Mall. Even before I understood how to read street signs or recognize landmarks, I’d catch a whiff—something between malty caramel and toasty almonds—and my nose would tell me our location on the route. Although I now prefer the aromas and flavors of bread that hasn’t been pumped with commercial yeast to speed up its fermentation, the smell of toasting Wonder Bread still fills me with indescribable joy.

When I teach Arab bread-baking workshops, I ask people what they love about bread, and nearly always, they say it’s the smell and the memories that smell elicits; that smell connects them to their culture and warms them with nostalgia for their childhoods. As bread meets your senses—smell, touch, sight, and, of course, taste—it pushes everything else away, leaving no room for other problems.

When I teach Arab bread-baking workshops, I ask people what they love about bread, and nearly always, they say it’s the smell and the memories that smell elicits; that smell connects them to their culture and warms them with nostalgia for their childhoods. As bread meets your senses—smell, touch, sight, and, of course, taste—it pushes everything else away, leaving no room for other problems.

When I entered culinary school and got serious about baking professionally, I was eager to learn the secrets to making great bread. I read every fermentation book I could get my hands on and enrolled in countless classes, but the language and approach felt intimidating and inaccessible. I couldn’t relate to the overwhelmingly white male voices and overuse of Eurocentric terminology coming through the pages of recipes and tutorials. I would often think to myself, “When should I use the word levain? Is it really any different from using the word starter? What is biga, then, and am I pronouncing that right?” It turns out they’re all stages and procedures in the process of making sourdough starter.

Bread baking, it seemed, was the domain of white male bakers and chefs. I couldn’t imagine myself thriving in this space or finding a mentor with whom I could feel excited, instead of feeling inadequate as I learned these concepts. That feeling of alienation was strong enough to keep me away from bread baking for years, focusing instead on sweet pastries.

But bread kept drawing me back. I was fascinated—and at times obsessed—with the alchemy of bread: just wheat, water, and salt, aided by hardworking yeast, that transform as if by magic into this life-sustaining food. Outside of the classroom, I studied the foundations of Arab baking by talking to elders, watching YouTube videos, and reading books in the library, discovering the sophisticated techniques and novel ingredients employed by Arabs over centuries.

Capturing “wild yeast” from the air to build sourdough bread starters was commonplace in villages spanning the Fertile Crescent, from Egypt to Lebanon. Each generation passed along its knowledge about the care and feeding of the living organisms fermenting their foods. Their wisdom was not confined to experts but was instead cultivated in homes from fathers to sons, mothers to daughters, and grandparents to grandchildren, since the act of baking bread was a family affair.

While I’m put off by the jargon of bread baking, it does bring out my inner nerd. I get as much joy from the science as from the connection to generations before me who used the same techniques I now use. Even today, after thousands of loaves, I get a little rush of excitement with each new batch of dough, watching, feeling, smelling its distinct features as it takes shape in my hands.

While I’m put off by the jargon of bread baking, it does bring out my inner nerd. I get as much joy from the science as from the connection to generations before me who used the same techniques I now use. Even today, after thousands of loaves, I get a little rush of excitement with each new batch of dough, watching, feeling, smelling its distinct features as it takes shape in my hands.

To Sourdough or Not to Sourdough?

One thing that makes the breads in my restaurant unique is they are made with “starter”—a fermented dough with natural yeast that allows for a slow rise. We spent three years building the starter, beginning with a small cup of starter brought over by a friend from Tartine Bakery. I debated whether to rely on natural fermentation to make thousands of rounds of dough a week. The wild yeasts can be tricky, and we struggled to scale up and manage inconsistencies in the beginning. But the wild yeast and bacteria create far more complex flavors than commercial yeast can do alone, so that is why I use both wild and commercial yeasts in my breads. At a certain point in 2019, we found our sweet—or shall I say sour—spot, creating a flatbread with delicious complexity that made it as interesting as the meats, cheeses, yogurts, and vegetables we serve on and with it.

I will never forget the day one of my regulars, a prominent Lebanese academic with strong opinions on Arab culture and politics, arrived for his dose of mana’eesh. He told me firsthand my bread was even better than the loaves made in Beirut. “It’s like how it used to be made,” he said emphatically. “Unfortunately, unless you go out to the villages, they don’t make it like that anymore.” I could think of no bigger compliment, and his praise solidified my commitment to learning about fermentation and continuing to perfect our bread at Reem’s.

My obsession with natural fermentation is probably no coincidence; it’s an ancient tradition dating back to the region of my ancestors, thousands of years before the invention of commercial yeast. In ancient Egypt, the creation of natural starter evolved from beer making. Breweries and bakeries often co-located and, not surprisingly, were run by women. Like many of the best inventions, the discovery was probably accidental. Most likely, the wild yeast spores spawned by beer brewing went to work on the flour and water which were mixed in the same clay pots for bread baking, and generated the same amino acids, alcohol, and gases that we now craft with great care to produce soft, chewy, heaven-scented bread. This discovery, several millennia later, connects me to bread as part of my own lifeline.

My obsession with natural fermentation is probably no coincidence; it’s an ancient tradition dating back to the region of my ancestors, thousands of years before the invention of commercial yeast. In ancient Egypt, the creation of natural starter evolved from beer making. Breweries and bakeries often co-located and, not surprisingly, were run by women. Like many of the best inventions, the discovery was probably accidental. Most likely, the wild yeast spores spawned by beer brewing went to work on the flour and water which were mixed in the same clay pots for bread baking, and generated the same amino acids, alcohol, and gases that we now craft with great care to produce soft, chewy, heaven-scented bread. This discovery, several millennia later, connects me to bread as part of my own lifeline.

Way back before I started my bakery and before sourdough starter became popular for home bakers in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, my only exposure to sourdough was at the iconic Boudin Bakery, located on Pier 39 in San Francisco. Though delicious as bread bowls with chowder, the loaves themselves didn’t appeal to me at the time—I preferred the malty sweetness of quick-rise breads and disliked the sour element. When I joined the Arizmendi Bakery & Pizzeria, a sister to the famous Cheese Board Collective in Berkeley, California, in 2011, I knew I’d have my hands in lots of sourdough. Tending the live cultures and tasting the breads we produced, my taste shifted away from Wonder Bread and toward the nuanced world of sourdough and the endless range of flavors it introduces. My appreciation for fermentation took some time, not unlike the process itself.

Reprinted with permission from Arabiyya: Recipes from the Life of an Arab in Diaspora by Reem Assil, copyright © 2022. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

Photographs copyright © 2022 by Alanna Hale

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.