Consider the Breadcrumb

A Wordloaf guest post from Jeffrey Rubel

Table of Contents

All this month on Wordloaf we’ll be talking about breadcrumbs, those wonderful byproducts of bread baking that sometimes (especially when working on a bread cookbook) we have more of than we know how to consume. To kick it off, we have this fascinating guest essay from historian Jeffrey Rubel, who writes The Curiosity Cabinet newsletter, about Joseph Lee, the African-American inventor of the first “bread crumber,” an automated machine for making bread crumbs.

—Andrew

Consider the breadcrumb. It’s a small fragment of bread — often forgettable, sometimes valuable. On the dining table, it’s a nuisance, a mess-maker. But in the kitchen, it’s an ingredient: Put it on top of casseroles, use it to coat chicken breasts, mix it into meatballs. This dichotomy raises a question: How does one deal with a tiny piece of bread that is useless in one context and useful in another?

Two different tools offer two different solutions.

Tools are often pathways to efficiency. The kitchen tool, while far from new, came into its own in the mid-1800s. With the technological advances of the Industrial Revolution, metal tool production became easy and cheap, enabling inventors to develop a plethora of special culinary devices. The raisin seeder. The eggbeater. The electric waffle iron. And relevant to this bread-themed newsletter: The bread crumber and the bread grater. Each invention claimed to save users time and energy. In turn, each invention has a story to tell — of an innovator on the hunt for efficiency, of a specific moment in our cultural history.

On the dining table: The Crumber.

John Henry Miller owned Miller Brothers Restaurant, one of the hottest and fanciest restaurants in early 20th century Baltimore. As a fine dining establishment, Miller Brothers’ reputation depended in part upon its service and cleanliness. Therefore, Miller cared about removing crumbs from his dining tables. Frustrated by how difficult it was to do this during a meal, he invented the “Crumb Scraper” in 1939.

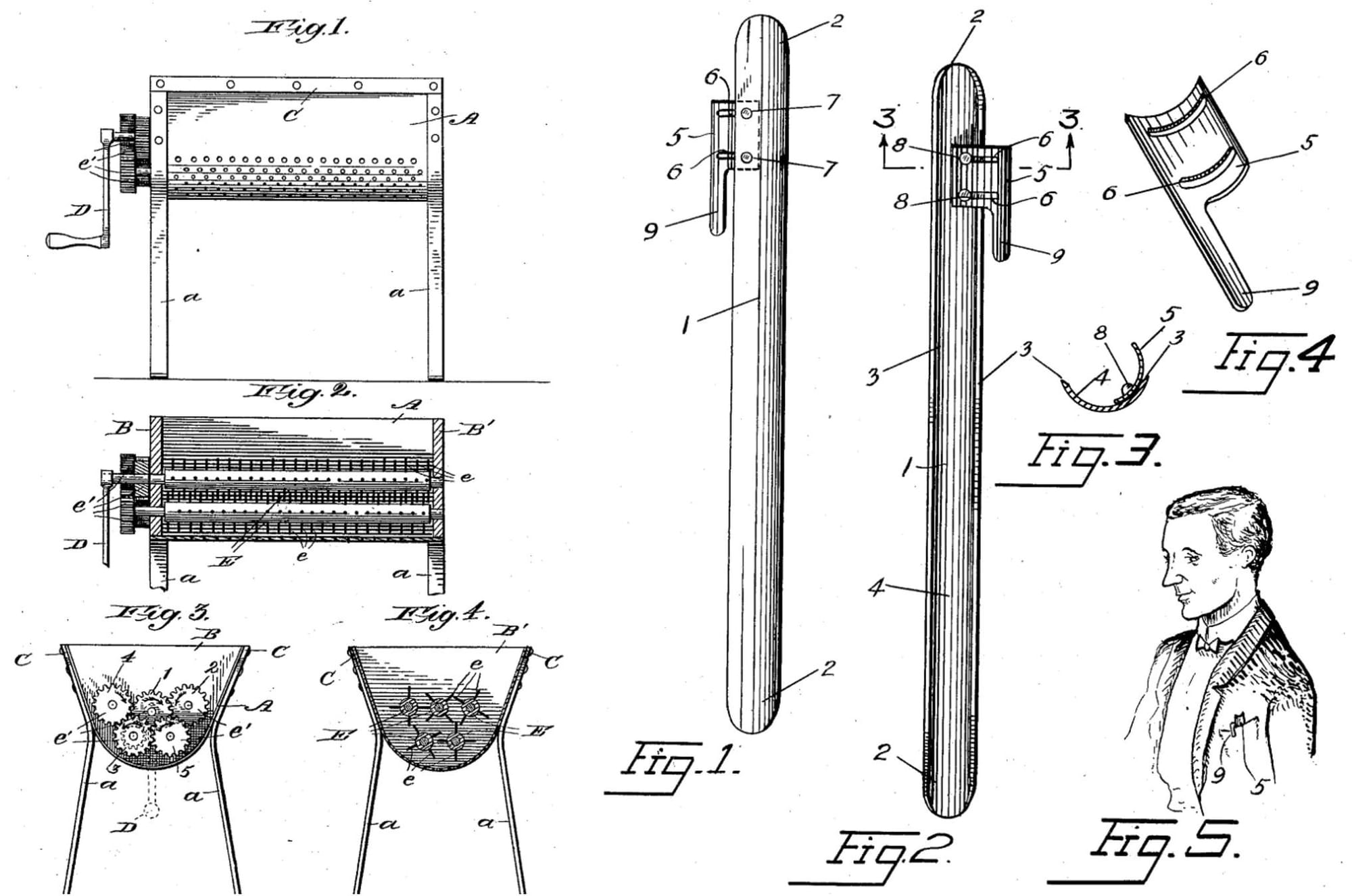

Miller’s scraper — a six-inch curved piece of metal — wasn’t the first. The tabletop “crumber” dates to Victorian England, when the tool was an elaborate silver brush and pan set. Miller invented his metal crumber because, in his words, the brush and pan were “cumbersome” and “disturb[ed] the diners at the table in its use, because of the relatively large area of operation required by them.” Miller’s smaller one-piece crumber could be used more inconspicuously. It’s still in use today.

No matter the design — Miller’s or the Victorian one — the crumber is a status symbol. In Victorian England, aristocratic households used them to show off their wealth at the dinner table. And, in the 20th century, the crumber was commonly found in fine dining restaurants. The purpose, always the same: Clean white tablecloths.

In the 15th century, the European aristocracy — seeking a way to distinguish their tables from those of commonfolk — turned to the white tablecloth as a sign of stature. At the time, it was difficult to keep a tablecloth white, so having a fresh, white tablecloth was a sign of wealth. Wealth that enabled a household to hire a large staff to keep tablecloths clean. Wealth that enabled a household to buy expensive white linens. Today, the white tablecloth is so embedded within our understanding of fine dining that, according to a 2019 Food Quality and Preference study, many modern diners consider table linen an important element of the restaurant dining experience.

The persistence of the white tablecloth has lead to the persistence of the crumber. The tool, by efficiently maintaining tablecloth cleanliness, also maintained elegance in upper class dining experiences.

In the kitchen: The Grater.

Joseph Lee, born to enslaved parents in South Carolina in 1849, amassed an impressive culinary empire in Massachusetts, including a hotel, an inn, and a catering business. As his business grew in the 1890s, Lee noticed how much bread was often wasted. So, he set out to solve this problem by designing a new tool. “By the use of my invention,” Lee wrote, “the scraps and crusts of bread which come from the table can be readily crushed and crumbed, thereby effecting a great saving in establishments where the bread waste from the table is considerable.” The crumbs could then be used in cooking.

Prior to Lee’s invention, grating bread for cooking was time-consuming. For instance, in Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1861), Isabella Beeton recommends home cooks purchase a “bread grater,” but using such a device in Beeton’s time required slowly raking a stale loaf against a grater, similar to how we grate cheese today.

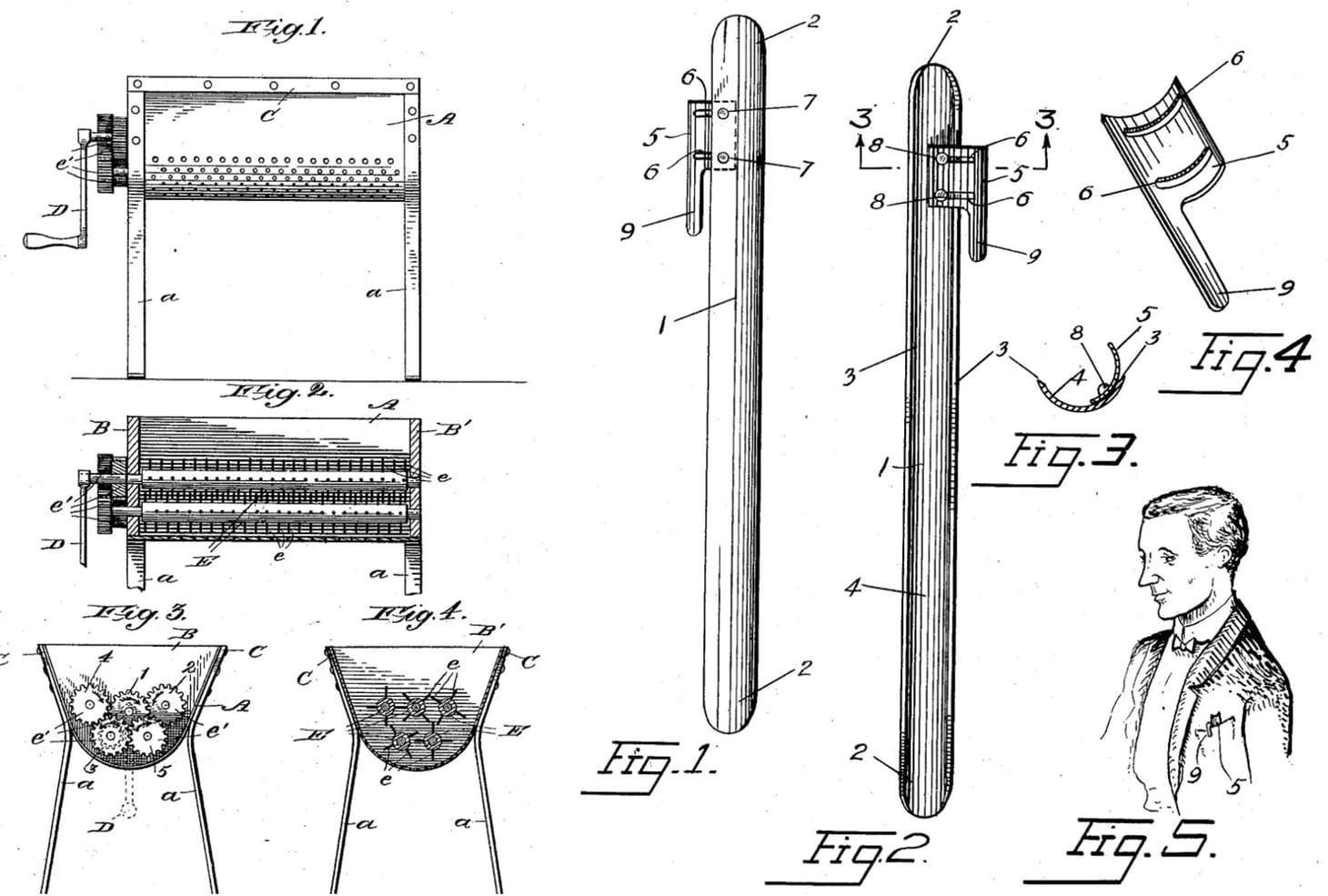

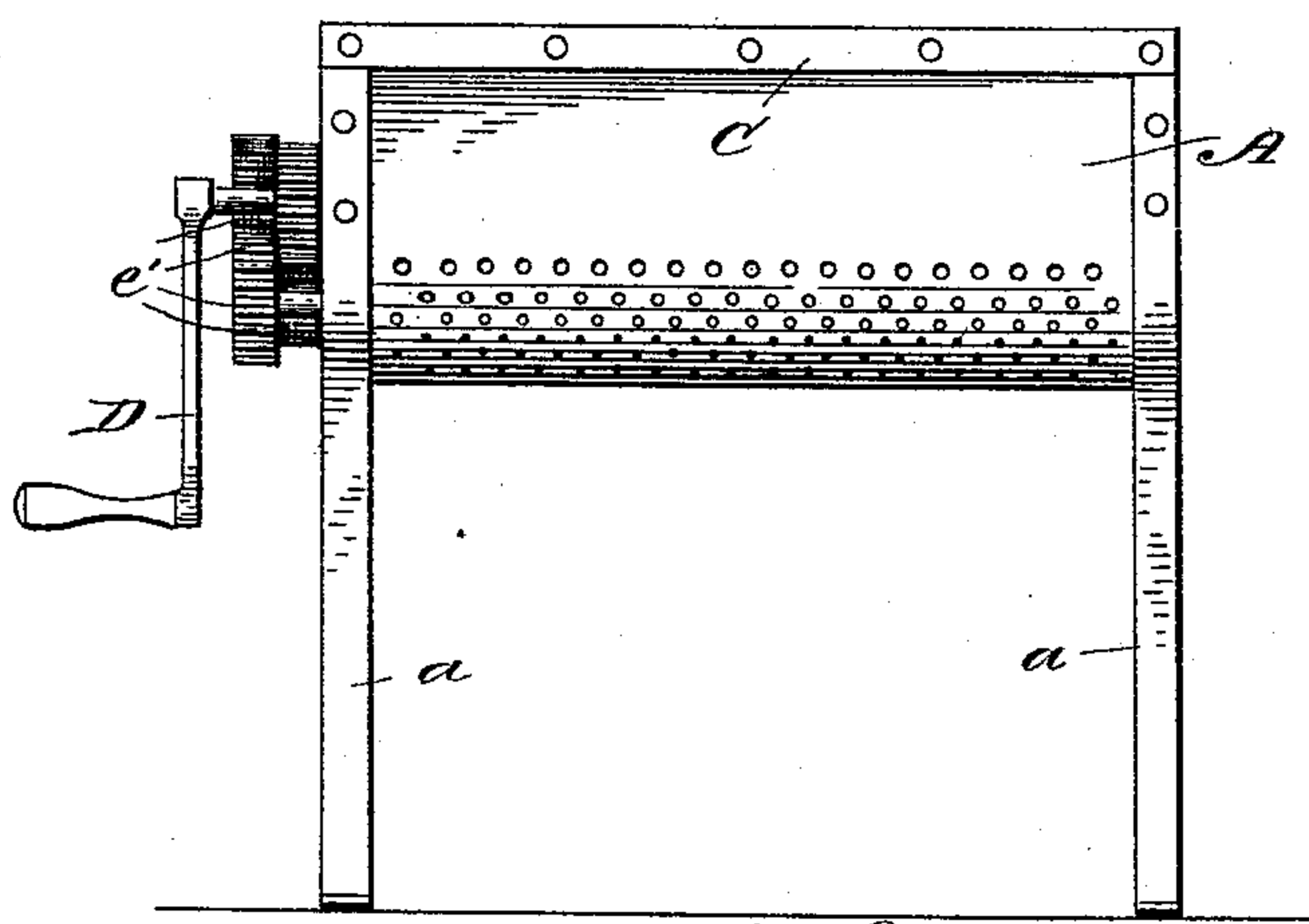

Lee’s invention, on the other hand, was efficient: It was an oblong metal container with holes along the bottom. A loaf of bread was placed on top, and as the crank was turned, the bread would be pulled through cogs, which would tear it into tiny pieces. It was perfect for the restaurant kitchen. He filed for a patent in 1895.

This patent is noteworthy. For Black men in 1800s America, obtaining a patent was no small feat. Until 1868, Black Americans couldn’t file for patents because the 1857 Dred Scott case ruled African Americans, free or enslaved, were not US citizens and thus could not file for US patents. In 1868, the ratification of the 14th Amendment guaranteed citizenship to anyone born in America, but filing for a patent was still difficult for 19th and 20th century Black inventors. According to economics professor Lisa Cook, segregation made it challenging for Black inventors to connect with patent lawyers, who were nearly all white and lived in white-only commercial districts, and with such limited access to legal systems, Black inventors often had trouble defending against patent infringement.

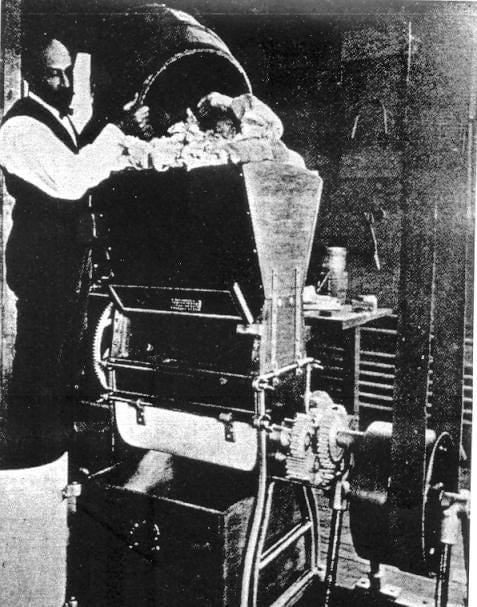

Despite these challenges, Lee successfully secured his patent (likely because he already had financial resources and connections thanks to his restaurant business). In 1901, he sold the patent to The Goodell Company, which began mass producing the grater. Within five years, major hotels and catering companies across the United States were using Lee’s machine, efficiently turning old bread into new breadcrumbs.

• • •

At the core of both inventions was a quest for efficiency in restaurants: Miller writes that his crumber can “pick up crumbs in any part of the table with facility and convenience,” and per Lee, his grater leads to “great savings in establishments where bread waste from the table is considerable.”

But, there is something more at play, too. Both inventions tell a socioeconomic story. Miller’s is one of elitism and fine dining, whereas Lee’s is one of racism and entrepreneurship. Each invention illustrates a confluence of cultural forces that drove two different inventors to address the same problem: What do you do with breadcrumbs?

Jeffrey Rubel is a historian of science and technology in American culture. He writes The Curiosity Cabinet newsletter, which explores everyday objects and the histories behind them. He has published articles on –– among other topics –– the history of fish preservation, the history of removing seeds from fruit, and the human sciences in Sondheim’s 1970 musical Company. When not writing about history, Jeffrey is the strategy director at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. He has a master’s in the history of science from the University of Cambridge and a bachelor’s in geosciences from Williams College. Subscribe to his newsletter for more stories like this tale of dueling breadcrumb technologies!

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.