Class Time: Desired Dough Temperature 101

Dialing it in

Table of Contents

Today’s post is on another less-than-sexy but important topic: desired dough temp, or DDT. But first, a couple of updates on how to read this newsletter for best results:

1) It’s always a good idea to read the newsletter on the website whenever possible, particularly after the post has been out for more than a day or so. I’m a team of one over here—baker, writer, photographer, and copyeditor, all—and it is inevitable that I make mistakes along the way, no matter how many times I double-check the copy before I send it out.

Thankfully, one or more of you is bound to point these errors or omissions fairly quickly on. And it’s my intention to update the posts online as soon as I learn of them, with clear indications that corrections have been made. So be sure to consult the online version—especially when attempting to make a recipe—so you know you have the most up-to-date and accurate version in hand.

2) Please take everything I say as literally as possible, particularly when it comes to recipes and technical information (and especially in headnotes and parentheticals). I strive to make my recipes and explanations as clear and thorough as possible, so that you’ll be successful in your baking.

Which is to say, conversely, that you should not make assumptions that you can go “off book” at any point in a recipe and still end up in a similar place as I do. You certainly might, but I can’t promise that you will, and—provided of course that I have done my job well—it’s not the fault of the recipe if something goes awry.

(Yes, all that should be self-evident, but based on some recent correspondence I received, it turns out it actually requires spelling out.)

Desired Dough Temperature, or DDT

[Photo credit: Getty Images]

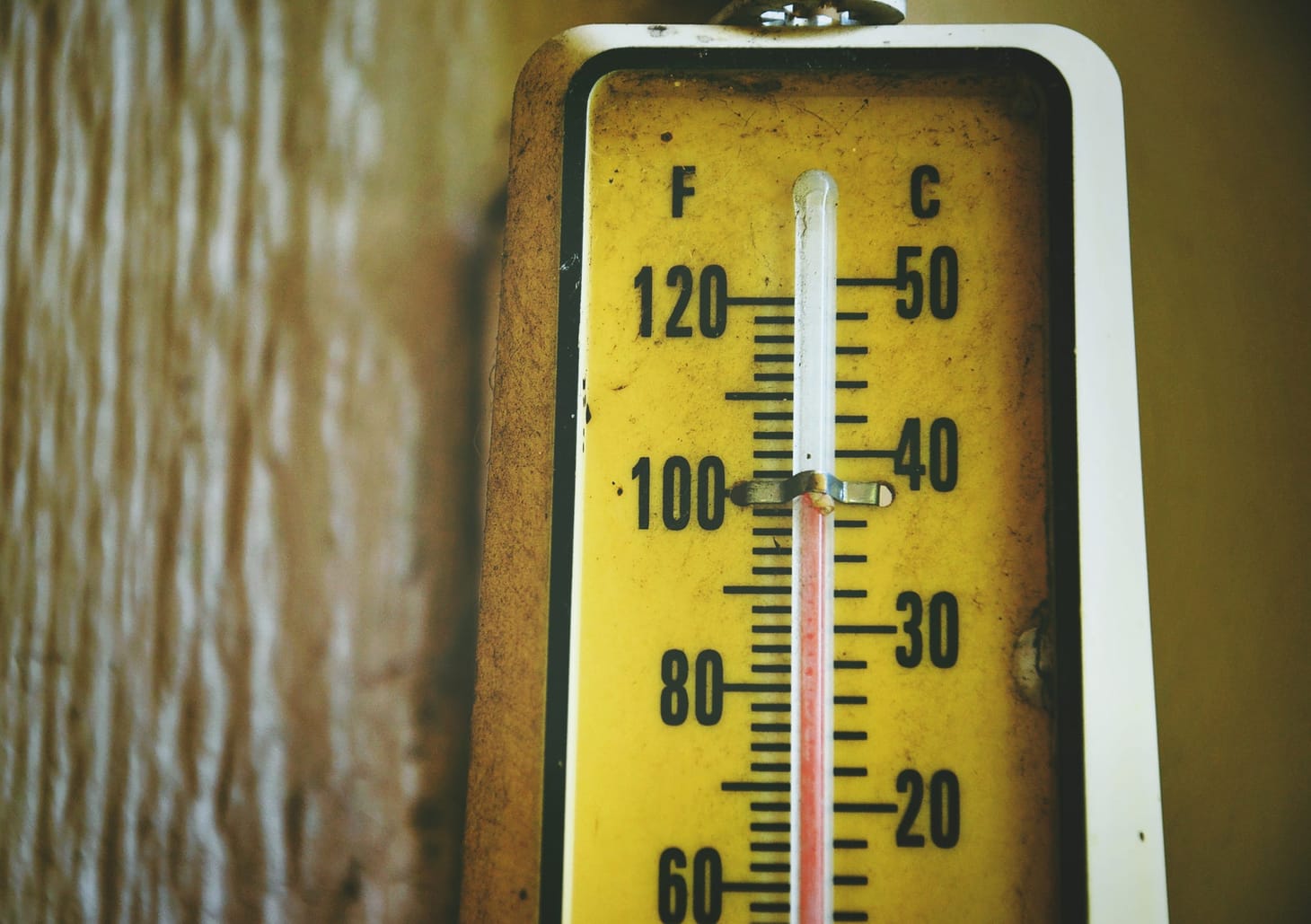

Just like human beings, yeast and bacteria have a “preferred” temperature for optimal living. Venture too far beyond this temperate zone and their happiness—and growth rate—suffers: Too cold and things slow way down, too hot and things move much too quickly.

The chemistry of fermentation shifts with temperature as well—cold temperatures promote the production of more acetic acid and less lactic acid; warmer temperatures invert this effect. But while prolonged fermentation of doughs at low (i.e., fridge) temperatures can be an effective way to alter the flavor or texture of a dough—or simply a convenient way to schedule baking—it’s rarely advisable to proof bread at temperatures much higher than “normal”, since the accumulation of acids will eventually degrade the structure of the dough. Moreover, carbon dioxide production—essential for loaf volume—slows down drastically at temperatures above 95˚F.

As with most humans, the preferred temperature for yeast and bacteria in bread doughs is in the mid-70s Fahrenheit. More specifically: 75˚F for yeasted breads and 78˚F for sourdoughs.

There’s another reason to want to control the temperature of your doughs: consistency. While working outside of these ideals is certainly doable—within limits—it makes predicting how long things should take challenging. Recipes are generally written with particular temperature conditions in mind; all else being equal, if things happen faster or slower than described, temperature is probably to blame.

If the temperature in your kitchen happens to be a consistent 76˚F, then—lucky you—you don’t really need to think much about dough temperature. The rest of us, however, need a way to control the temperature of our doughs, despite ambient temperatures being far from the ideal. (It was in the 90s here in Boston only just a few weeks ago, and right now my kitchen is a balmy 66 degrees.)

Of all the major ingredients that go into our doughs—flour, water, and preferments such as a levain or biga—there’s only one of them that a baker can adjust the temperature of easily: water. Thus, to mix a dough and have it end up at a desired temperature, you take the temperature of the fixed elements and use the results to calculate how hot or cold to set your water temperature. This is what is known as calculating for the desired dough temperature, or DDT for short.

Many bread recipes—if they mention temperature at all—call for water of a specific temperature. This is a sort of shorthand, “cheater” approach to DDT, because while it does attempt to set the final dough temperature, it doesn’t take into account the temperature of everything else. Any “serious” bread recipe will list the DDT in the step immediately after mixing is complete, often on its own line, so you know exactly what to aim for. (Occasionally a recipe will have a DDT that is other than the “ideal” 75 or 78˚F temperature. For example, many of my yeasted pizza doughs are meant to cold-ferment from the get-go; with those, I aim for a DDT no higher than 65˚F so fermentation ramps up slowly.)

One thing to know about the DDT formula is that it’s not an exact science. Bakers who mix doughs on a daily basis learn to make adjustments to their calculations based upon experience. Nevertheless, it’s still a useful tool for getting things in the right ballpark, and over time you’ll get better at making it work precisely.

My version of the DDT formula looks different than others you may have seen elsewhere, though the underlying math is pretty much the same. What I do is I take the differences between the temperatures of each of the components in my dough and the desired, “ideal” temperature—75 or 78˚F, depending upon the type of dough in question—and then add them all together to get the final water temperature:

A = 75 or 78 - [flour temperature]

B = 75 or 78 - [room temperature]

C = 75 or 78 - [friction factor]

D = (75 or 78 - [preferment temperature]) x [preferment %]

A + B + C + D = Final water temperature - “Flour temperature” is just that, the temperature of your flour.

- “Room temperature” really means bowl temperature, i.e., it’s there to account for the way the temperature of the mixing bowl impacts the final temperature of the dough. If you have an infrared thermometer, you can take the bowl temperature directly for more accuracy. Otherwise just use the room temperature as a stand-in for it.

- “Friction factor” is a number that accounts for the heat generated by the mixing method in question. This will vary depending upon the specific device used, but I tend to use 5 for hand mixing (yes, even gentle hand mixing will warm a dough somewhat), 25 for a stand mixer on medium speed, and 30 for a food processor.

- If your dough doesn’t have a preferment such as a levain or biga, then you just skip line D altogether.

- “Preferment %” is the percentage of preferment relative to flour. This is my particular tweak to the standard DDT formula. I noticed that my calculations were sometimes off, especially when I was working with levain from the fridge and there was only a relatively small amount of it in the overall formula. So I decided to sort out some way to account for the ratio of preferment in the dough, to better estimate its true impact on the final dough temperature. What I now do is determine the difference between the DDT and my preferment temperature and then multiply the result by the preferment percentage.

As with baker’s math, this all makes much more sense in practice. Here’s an example, with numbers I took in my chilly kitchen just now, for a hand-mixed sourdough containing 20% levain:

78 - 66 [flour temperature] = 12

78 - 66 [room temperature] = 12

78 - 5 [hand mixing] = 73

78 - 40 [levain temperature] = 38 x 0.20 [levain %] = 7.6

12 + 12 + 7.6 + 73 = 104.6˚F water temperatureThat water temperature seems hot, but there’s a lot of “cold” to counteract in each of those numbers to bring the final temperature up to 78˚F. (Note that if I had not adjusted for the preferment percentage, the actual water temperature would have been 131˚F.)

Or in the summer, when I’m making a yeasted, stand-mixer-mixed dough:

75 - 82 (flour temperature) = -7

75 - 84 (room temperature) = -9

75 - 25 (stand mixing) = 50

-7 + -9 + 50 = 34˚F water temperatureAgain, that sounds cold, but there’s a lot of heat to counteract in order to hit 75˚F after mixing is complete.

Hopefully this all makes sense and is easy to put into practice. It really does become second nature after awhile. (Expect to see DDT numbers in recipes here going forward, now that I’ve explained how it works.) If anything seems confusing or needs more detail, please let me know.

—Andrew

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.