Book Excerpt: Breadsong

by Kitty and Al Tait

Table of Contents

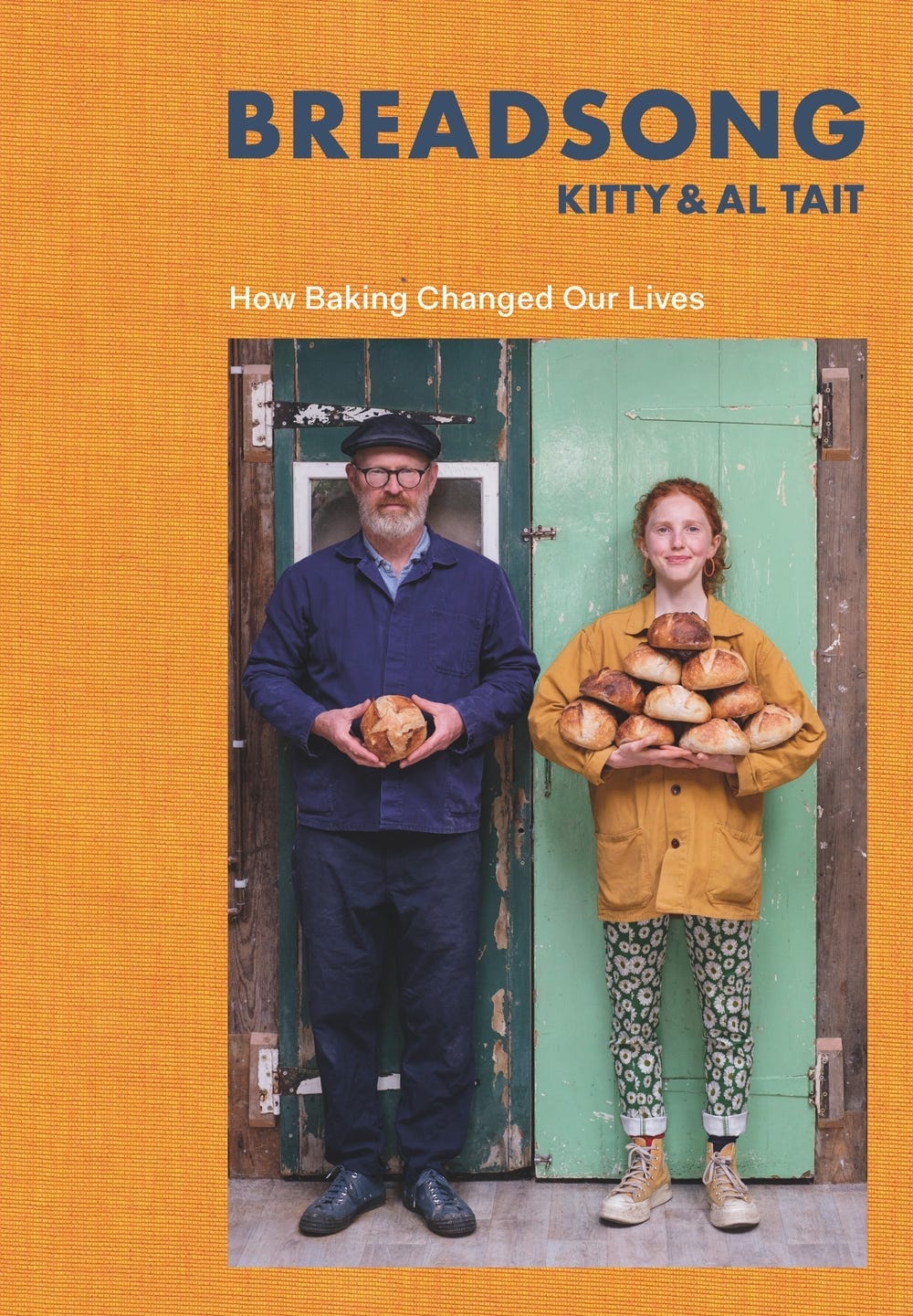

I’m still on the road in DC after my sourdough workshop with Tara Jensen, which is why this week’s emails have been all of a jumble. I’ve got a quick Friday Bread Basket to come later today, but first I want to share a book excerpt from Breadsong: How Baking Changed Our Lives, by Kitty and Al Tait, daughter and father owners of the Orange Bakery, in Oxfordshire, England. Breadsong is a bread cookbook, with many wonderful recipes, but it is also much more than that, since it tells the tale of the bakery’s founding, and how the discovery of bread and baking lifted the then 14-year-old Kitty out of a debilitating, all-encompassing struggle with anxiety and depression. It’s the story of how bread gave Kitty a reason to get out of bed in the (early) morning, one I’m sure will resonate with everyone here.

—Andrew

Wordloaf is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The First Loaf61.3KB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownload

Chapter 2: THE FIRST LOAF

DAD MADE BREAD one day. I was sat on the kitchen stool thinking

of nothing while Dad mixed flour, water and salt in a bowl to make a dough.

It looked gloopy, anaemic and sludgy – a bit like how my brain felt. Dad draped the primary school tea towel (the one printed with the faces of my classmates) over the top of the bowl and tucked it away on a shelf. The next day, when

I’d finally made it downstairs, Dad had taken the bowl off the shelf and it was sitting back on the kitchen table. I lifted the tea towel to see if the dough looked as unappealing as the night before. It was now like the surface of the moon.

The dough was gently bubbling and as each bubble popped another opened. It was alive.

I WISH I could remember the first time Kitty and I baked a loaf together. In reality, it was just another activity that I was trying out with Kitty that might provide her with some kind of distraction.

TV was no good as she couldn’t concentrate for anything longer than a few minutes. We’d tried gardening, although after choosing a few flowers and planting them out there wasn’t much to do except watch Sibby dig them all up again. We’d experimented with craft, but that proved pretty useless. Sewing briefly lit up a few embers, but our ambitions went way beyond our ability. We painted for a bit and then when that failed, I got a bigger brush and slapped emulsion on a few walls. I was running out of options. Bread baking was pretty far down the list, but I enjoyed it, so we did it.

Bearing in mind how long I had been baking bread, the standard of my loaves was shockingly low. I’d been baking on and off since being a student. I even did a course once, a gift from my siblings for my fortieth birthday, and yet still I seemed to defy Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000 hours maxim. The more effort I put in, the more inconsistent my loaves seemed to be. Dense, doughy and flavoursome, but never things of beauty and rarely presentable, even to the rest of the family.

Bread baking was something I would do on holidays if I found a bit of yeast and space, or on occasional weekends. The course I had taken encouraged working with a very wet dough – although for me, this meant I never got beyond the stage where the dough stuck to our wooden work surface.

However hard I tried, the kitchen looked apocalyptic after 10 minutes of kneading and scraping dough.

The children occasionally shared my enthusiasm when a loaf was fresh out of the oven, but then half-eaten hunks sat forlornly at the bottom of the bread bin, gradually evolving into rocks, easily outranked by something soft, white, sliced and plastic wrapped.

Then someone pointed me in the direction of Jim Lahey’s no-knead bread method that involves no kneading and, consequently, very little mess. You simply mix flour, water, salt and a tiny bit of yeast (1/4 of a teaspoon at most) together in a bowl and leave it overnight. Initially it looks like wallpaper paste but then the dough starts to ferment and, in the morning, it is a slightly sour, bubbling mass. All you do is shape the dough into a vague ball, put it onto some parchment paper and let it prove before baking in a cast-iron casserole dish that you shove into your oven at its top temperature for 30 minutes or so beforehand. Compared to my usual bread breeze blocks, with this method the end product was semi-professional in appearance and tasted quite different to anything I had made before. These loaves went down well with the family and got eaten fast.

It was this no-knead method that I shared with Kitty. I can’t tell you what time of day it was, what we’d been doing that morning or how it cropped up in conversation. There was nothing planned about it. I just asked Kitty if she wanted to have a go herself. There was no hallelujah chorus or a blinding flash of light. What I do remember, though, was that she actually looked interested when we pulled the loaf from the oven – and that hadn’t happened in a long time. I had no idea just how important that moment was, and I still didn’t when Kitty asked to bake that bread again.

I’D NEVER BEEN a good cook in any way at all. I didn’t bother to follow the ingredients for a recipe, I just shoved together a whole load of things that I liked. The most basic things went wrong, like my banana bread that sank in the middle and my fairy cakes that dried out your whole mouth because I got confused between a teaspoon and a tablespoon when adding the bicarb. I don’t come from a family of cooks either. Mum makes two things: ‘dogs’ dinner’, which is mince and rice, and cheesy risotto, which is cheesy risotto. Dad’s a much better cook, but his repertoire is very stew-based. Sausage casserole with baked potatoes came around a lot.

But Dad’s breadmaking was different. He showed me how he made the dough, proved it, shaped it and then put it in the casserole to bake.

When he lifted the lid, there was this beautiful crackling, singing loaf that made the hairs on the back of my neck shoot up.

It was alchemy. Something so dull had transformed into something so brilliant. Like the girl who could spin straw into gold, I could do it too. And so I did it again and again and again.

OUR FAMILY REALLY like bread, but there was no way our consumption was going to keep up with Kitty’s rate of baking. Two weeks in, when Kitty began experimenting with some whole wheat flour as well as white, we started to face a small mountain of loaves pushing up the lid of our bread bin. It was Katie who suggested asking our neighbours if they wanted a loaf. We live on a one-way street of fifteen houses, all different shapes and sizes, with a mix of families big and small and a few elderly people who live on their own. We knew all of them and so we set off to ask them (or rather beg them) if they might like some fresh bread. Everyone who was at home when we knocked said yes and Kit went home to start preparing the doughs.

The next day we baked five loaves and wrapped them, still warm, in parchment paper and delivered them to our neighbours. They were received with the same kind look that you give to children selling off heavily iced cupcakes outside the school gates to raise money for something. It was a genuine surprise when Juliet, who lived a few doors down, told us that her children had devoured the whole loaf and asked if she could she put in an order for another.

For those first few weeks nothing really changed. Days began very early and we were all mentally and physically exhausted by the evening, often going to sleep when it was still light outside. The sense that we were living in some strange experiment continued. Sibby carried on destroying our sad flower beds. Katie and I played tag being with Kitty, helped by Aggie and Albert.

But there was this small seed of routine.

Kitty would make up a clutch of doughs before bed, then in the morning we would bake, wrap and deliver the loaves up and down the street. Just for a moment – sometimes when she shaped the dough into a ball, when she lifted the lid off the casserole or when she handed over a still-warm wrapped loaf – I would see her smile a real smile. A smile uncluttered by the thoughts crowding her head. A genuine smile of her own rather than a forced one she felt she needed to give.

I STARTED TO live for that small window of time each day when I could bake. The problem was there was only a limited amount I could do. Our oven could only get so hot and it took two hours to cook each loaf. I could make up a lot more dough, but I had nowhere to bake it. I needed more ovens. It was Juliet who offered first. They had just put in an amazing new convection oven that could take four casserole dishes at a time and reach much higher temperatures than ours. Juliet said I could use their oven any time and I was just to let myself in when I needed to.

A routine was set.

I would wait until they’d finished with their kitchen for the night and then scuttle across the street.

As this was around 9 pm, I would normally have changed into my fleecy pyjamas with a coat thrown over the top so I could go straight to sleep afterwards. With two old casserole dishes stacked on top of each other, I would push through their back gate, down their side alley and into their kitchen – saying hello to their dogs, Coco and Boris – then I would quietly slide the casseroles into their oven, trying not to disturb the family if they were watching TV in the next-door room. I repeated the journey as I needed to heat four casserole dishes in the morning, but I could only carry two at a time. I had to say hello to the dogs all over again though. Back at home, I would mix up the flour, water and salt in a big bucket and then go to bed.

At 7 am the next morning I would scoop all the bubbly dough out of the bucket, lay it on the kitchen table, dust it with flour and roughly shape it into four balls. I would place each ball onto a sheet of parchment paper, which would then be lowered into its own glass bowl and a shower cap stretched over the top. (We started running out of bowls and soon I was using anything vaguely round; we lost our always-empty fruit bowl and once I even used my bicycle helmet.) The dough would then prove for two hours. Meanwhile, Juliet would turn on her oven when she woke up so that the casserole dishes would get very hot. By the time I went back over with the bowls of proved dough at 9 am, Juliet and her husband Rick would have left for their garden nursery with the dogs, dropping Iris and Noah off at school on the way.

I would carefully take the hot casseroles out of the oven, lift the lids and lower each dough ball on its paper onto the base.

All the while, I tried hard not to burn my arms on the hot metal, which I did most of the time.

I would go home briefly and then return in 30 minutes to reach into the oven and lift off the lids to release the steam, again trying to avoid scalded skin. But I still wasn’t done. The loaves had to finish baking uncovered for another 15 minutes to form a golden brown crust. I spent that time sat on Juliet’s work counter, following bakers on Instagram and reading post after post about recipes, tips and experiments.

The bread baked in Juliet’s kitchen was so much better than the loaves we pulled from our old oven. The dough sprang up in the higher heat and baked in half the time. The demand for my bread in our street soared and so we bought a whole load more casserole dishes at the local Sue Ryder shop and I asked Charlotte and Phillip two doors down if I could use their oven as well.

Each evening I would go between houses, like a quiet elf in my soft pyjamas, carrying casserole dishes to slide into their ovens.

The next day I would trot between kitchens, lifting and lowering doughs and removing lids, leaving a small trail of flour and parchment paper behind me. By now I was making eight loaves each day. Even with giving out bread along our street, we still had loaves left over. I wanted to find them homes.

We wrote a list of all the people we knew well in Watlington (about three- quarters of the town’s population) and dropped a loaf of fresh bread in a brown paper bag on their doorstep. We put a handwritten note inside each bag that had Dad’s number on. The bags of bread went everywhere: the hairdressers, the butchers, old teachers’ houses, the care home at the top of the hill, the fire station, Iggy the postman’s house, the homes of friends we knew and houses we simply liked the look of. For a day we heard nothing. We worried that people thought they had just been bread-bombed. Then the texts started to arrive. ‘Great loaf. Would love another one. How much do I owe you?’ Orders went up to ten loaves a day.

Our subscription service was born.

Excerpted from Breadsong: How Baking Changed Our Lives. Used with the permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury. Copyright © 2022 by Kitty and Al Tait.

Wordloaf is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.