On Our Own Terms: How Cottage Bakers Have Reclaimed and Transformed the Domestic Space

A story by Keia Mastrianni, from ATK's 'When Southern Women Cook'

Table of Contents

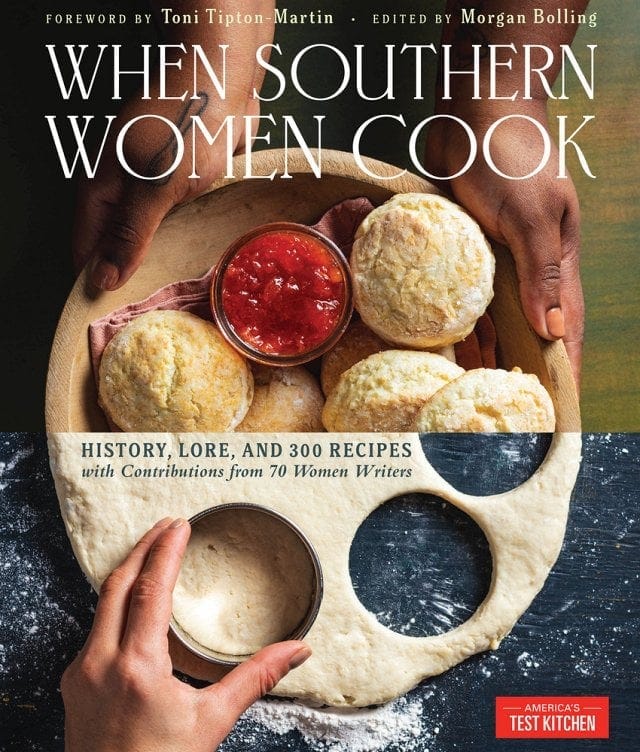

America’s Test Kitchen recently published When Southern Women Cook, a tribute to the vast contributions that Southern women have made to American foodways. It was created and edited by Toni-Tipton Martin and my friend Morgan Bolling, both of whom are from the South themselves. The 500-plus-page tome contains more than 300 recipes of Southern dishes of all kinds (including many breads and baked goods), polished and foolproof-ed in ATK’s usual careful style, and presented in a gorgeous, vibrant package.

Unlike most previous ATK books, crafted nearly entirely in-house, When Southern Women Cook includes the contributions of many from outside ATK’s walls—it contains essays and recipes from seventy Southern women authors and chefs, among them (who served as consulting historian for the project), Reem Assil, , , Doris Hô Kane, , Shane Mitchell, , , and Kayla Stewart. It lets Southern women cooks speak for themselves, appropriate for a book about such an important subject, making it a new sort of book for the brand, one that forefronts and celebrates the cooking taking place beyond its walls. When Southern Women Cook is a special book, one I’d recommend to anyone interested in Southern history and foodways (or just damn good cooking alone), right alongside Anne Byrn’s Baking in the American South.

I asked Morgan if I could share some excerpts from it, including this essay from Keia on Southern women cottage bakers, along with another (and a recipe) from Dawn Orsak on the Texas-Czech pastry klobásníky, which I’ll send out separately.

Also: I have a copy of this book to give away to a randomly-selected Wordloaf paid subscriber. If you want in on it, leave a comment below with your favorite Southern cookbook, chef, or dish (bonus points if they are from a female author or chef). As always: Please pay attention to your notifications, so I can let you know if you are a winner! I had to redo the last drawing because I couldn’t get the initial winner to respond.

—Andrew

On Our Own Terms: How Cottage Bakers Have Reclaimed and Transformed the Domestic Space

Grace Garay sets her alarm anywhere between midnight and 2 a.m. That’s when she rises to bake for customers who will line up in front of her Orlando home on Saturday to pick up their muchanticipated pastry orders from Nomad Bakehouse. Garay lives in the periwinkle-colored house with her mother, Miriam Zaldivar McCullough, and operates Nomad, her cottage baking business, from the same address. In a typical weekend, Nomad Bakehouse produces 450–500 pastries and 80 loaves of naturally leavened sourdough bread from the micro-bakery space. By morning, Garay has filled speed racks with delectables made with whole-grain flours and local produce, flaky layers of laminated pastry, tall biscuits, golden brioche buns, and cookies the size of your head.

Garay is a first-generation American with Puerto Rican and Honduran roots. Her mother came to the United States in the 1980s, traversing Mexico in search of a better life. Common to the immigrant experience, Garay’s mother worked tirelessly to provide for her family without the luxury of choosing her own path. She simply worked. That ethic suffused Garay’s mindset with an ideal she’s carried into her own life.

“We’re women and we’re capable of doing anything we need to do,” she says. On visits to Honduras, Garay saw women setting makeshift tables on their patios and calling it a restaurant, rolling up their sleeves to get the work done while creating community, a natural extension of Honduran culture. Though Garay was classically trained with years of experience in high-volume bakeries, restaurants, and hotels all around the United States (hence, the nomad in Nomad Bakehouse), the industry wore on her. Its people and systems amounted to abusive work environments, thankless long hours, and a bottom line focus that lodged in her work-weary body. She sought a better way. Inspired by a connection to whole-grain flours and spurred by necessity, Garay carved a new path.

“Cottage allows you to build something entirely different,” she says. In its earliest references, cottage referred to “a variety of commercial activity or trade, which is carried out partly or wholly in people’s homes.”

From the Nomad website: “When the Covid Pandemic threatened our food supply, I was presented with the opportunity to feed my community on my own terms and from within my own home, with ingredients I respected.”

In Atlanta, Georgia, the line for Osono Bread snakes across the concrete lot minutes after the Grant Park Farmers Market’s opening bell. Beneath the market tent are Betsy Gonzales and her sister, Taylor Gonzales, displaying wooden planks lined with loaves of naturally leavened bread—Pullman loaves and multigrain loaves, milk bread and oat porridge boules. In the pastry case are cardamom buns and crumb cakes and Osono’s legendary brioche doughnuts in flavors such as ube, crème brûlée, pistachio, and horchata.

Betsy Gonzales is a first-generation American. Her mother, Eldi, emigrated from Guatemala in the 1980s, a single mother to two young girls. Gonzales attributes her entrepreneurial spirit to her mother, having witnessed the importance of autonomy and independence from a young age. “When you are a first generation child, you know what your parents are doing, and the sacrifices they make,” says Gonzales.

When baking came to the fore, Gonzales couldn’t afford the traditional culinary route, something not uncommon for women of color, who often face barriers to launching businesses and equitable access to economic opportunity. Gonzales, instead of going through formal schooling, took a job at Little Tart Bakeshop in Atlanta before creating her own immersion program: Using the powers of Instagram, she reached out to bakers in Europe and asked if she could travel to learn from them. What she found in Europe were small teams of one to three people producing high-quality, naturally leavened bread and pastries at scale. She returned home ready to bake, planting the seeds of Osono from her home oven while working her Little Tart bakery job. Slowly, she outfitted her home with professional equipment. By 2018, she developed a bread subscription service. A year later, she established a relationship with local farmer Brent Hall of Freewheel Farm to sell directly to consumers, and in 2020, when she was furloughed from her job due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Osono Bread launched into markets full-time, garnering press and accolades across city papers and beyond.

For Gonzales, cottage baking fosters introspection: What values matter to me? How can I share with my community? More than that, the bakery is a space to reclaim her power and autonomy as a brown, queer woman: “My experience has always been something I have to prove. Engaging in this model has allowed me to play in this space. I do everything a typical baker does, I’m just not zoned commercial. As a first-generation American, why wouldn’t I want to do this?”

Across the long arc of history are the twin threads of nourishment and survival woven together by women’s work in the kitchen. For centuries, the domestic space, and the food and care work performed there, was the heart of a woman’s world, and a place that was historically invisible and devalued, even as it sustained whole villages and fueled political movements.

For immigrant women, this space is a means of survival and resourcefulness when economic and social barriers muddy the prescribed path. So many find a way, whether it’s making injera from home, selling tamales out of the back of a truck, or dishing out plates from the garage or backyard; the list goes on, and it is work women have been doing ever since the first fire was stoked.

In cottage bakeries all over the South, bakers are changing the paradigm of what it means to work from home, bringing the artisanal into the domestic space, bucking industry norms, and reclaiming their power and connection to local food systems. If ever there was a space worth reimagining, the kitchen is it.

By Keia Mastrianni, writer, cookbook author, baker, and photographer based in western North Carolina.

Excerpted from When Southern Women Cook, by America’s Test Kitchen, Toni-Tipton Martin, and Morgan Bolling. Shared with permission from America’s Test Kitchen, all rights reserved.

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.