[So this is basically a first draft of a chapter from my book on making and baking 100%-rye breads my way. It’s nearly 4000 words long, which is a lot, I know. It’s also far too many words for a book, despite being a rather abbreviated overview of a process that really needs its own book to do justice to. One of my biggest challenges in writing the book has been condensing this sort of information down to a format that doesn’t blow out my word count before I even get to the recipes.

I was originally going to send this to my testing group—hi, testers!—but I thought it might be of interest to everyone, so here you go.]

I've long been a fan of using rye flour in my baking, but I have mostly avoided dabbling in whole-rye formulas, both because I thought they were hard to pull off successfully, and because I wasn't sure if I really liked them. I don't really like sour sourdough bread, and ryes have a reputation for being aggressively sour.

But nowadays I am all-in on ryes, and love them just as much as I do my wheat sourdough children. They aren't hard to make, once you know what to look for, their flavor and aroma is complex and rich (they need not be super sour), and they keep for weeks. They also smell amazing in the oven, even when they contain nothing in them other than rye flour, water, and salt, exuding an intoxicating melange of warm spices, roasting coffee, chocolate, and leather. I fell hard for ryes even before I sliced into my first loaf, all thanks to the aroma wafting through my kitchen.

One hundred-percent rye sourdoughs—or those with a greater percentage of rye to wheat flour in them—look, behave, and are made very differently to wheat sourdoughs, so if you want to tackle them, you'll need to learn to think in new ways. Fortunately, rye sourdoughs are mostly easier than wheat ones, once you adjust your mindset, especially the types of formulas I have included here. The dough can be mixed by hand or machine, the loaves don't necessarily require shaping, and it's fairly easy to judge when they are ready to bake. Which is not to say there aren't pitfalls ahead, but once you understand how sourdough ryes work, they are easily avoided.

There are many different strategies for fermenting rye sourdoughs, and I don’t claim to be an expert on any of them. I have tried a few and had success, but I'm focusing only on the simplest and most reliable method I've found, one that I think makes for a great "starter" rye process, one that doesn't compromise anything for being straightforward. Once you've learned it, you might want to try others, though I think this one adaptable enough to serve you for a lifetime.

One thing that is common to most 100% rye sourdoughs is that, relative to wheat-based sourdoughs, rye sourdoughs typically contain a much greater amount of prefermented flour, from 30% to up to 60% of the total flour. Additionally, unlike wheat sourdoughs, in ryes, most of the total fermentation happens well before the final dough is mixed. The preferment (or preferments, in the case of multi-stage sourdough ryes) proofs for as long 18 hours; once mixed, however, the final dough only needs a handful of hours before it is ready to bake. (Retarding is almost never done with whole-rye breads.)

The stages of rye sourdough fermentations

Like wheat-based sourdoughs, the simplest forms of rye fermentations have a single stage: the preferment is mixed using an active rye-based starter as the seed, proofed for 12 to 18 hours at moderate temperatures (70-80˚F/21-27˚C), and then used to build a dough. This is an effective approach and one that can be used to make just about any style of rye sourdough. (Bakers usually refer to rye preferments as sours rather than levains, since the practice is based upon German and not French techniques.)

Other rye fermentations are done in multiple stages, with each stage done at different temperatures and hydrations, in order to produce specific effects. They aren't all that hard to do, but they do require more precise temperature control to achieve the results that the extra effort is meant to produce. For now, I think the single-stage approach is plenty good enough for most (myself included).

On rye flour

All of my 100%-rye sourdough breads are made exclusively with unsifted, whole-rye flour. Rye flour in general is hard to come by, especially whole-rye. “Light” and “medium” rye are sifted, and even flours labeled as “dark” rye are suspect; be sure the packaging (or miller) specifically indicates that the flour is whole-grain. In my experience, the easiest way to acquire whole-grain rye flour is to purchase it from a regional miller—Carolina Ground, Ground Up, Barton Springs, Maine Grains, and many others—or someplace like Central Milling.

Another issue with supermarket rye flours, if you can find them, is that they may well have been milled long before you purchase them, which can lead to issues with fermentation due to higher falling numbers (i.e., decreased amylase enzyme activity). Flours from regional millers are bound to be freshly-milled, clearly-labeled, and selected and milled specifically for use in rye breads.

You can also mill your own if you have a tabletop mill, which ensures maximum freshness. Again, the best source for rye berries is from a regional miller, since you can be sure the grain is suitable for use in bread baking.

Assuming you can find or mill your own whole-rye flour, the biggest question is how your particular rye behaves when combined with water. Each flour will have its own unique absorption rate, so it is entirely possible that you will need to fiddle with the hydration to get doughs that are similar to mine. (See below where I talk about "flow," so you'll know what to look for.)

Preparing a rye starter

Here's one key that sourdough ryes differ from wheat ones: They work best when the starter is fed regularly with rye flour or at least whole-wheat flour. If your starter is white flour-based, it will probably behave sluggishly at best if you build a rye sour with it. (This is the main reason I feed my starter with a 50-50 mix of whole wheat and rye: it keeps it ready for any of the sorts of sourdoughs I like to make.) If you are serious about ryes, I'd recommend making a separate rye-based starter that you maintain alongside your wheat one (or switching over to a "universal donor" rye-whole wheat one like me).

If you have a wheat-based starter already, there’s no need to start a rye one from scratch, you can simply convert it. The culture will likely need a little time to adjust to the new flour, but it won’t take long.

Begin by introducing the culture to rye flour:

10g whole-rye flour

10g whole-wheat flour

17g water

5g wheat-based starter (any hydration)

Proof at 70–78˚F (21–25˚C) for 24 hours.

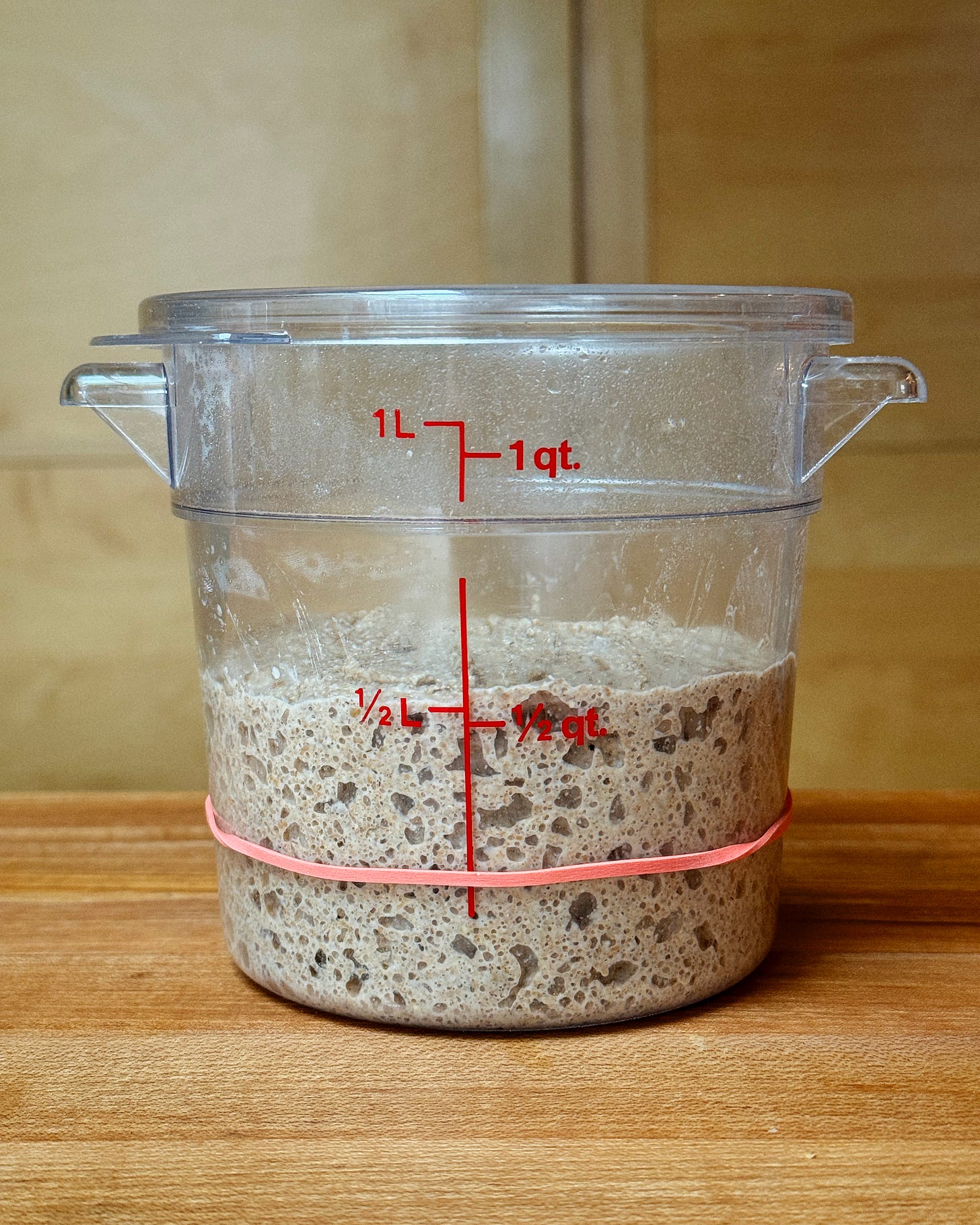

After this, use the same formula, but with the new rye culture in place of the wheat one. Repeat daily until it is reliably expanding to about double in volume within the first 12 hours or so, 4 to 7 days. The culture may go through a fallow period after the first few refreshments, but just keep at it, it should rebound within a few days. Once it does, it should be ready for use, and you should have a good idea what a healthy, active one looks like.

Daily rye starter maintenance formula

The above formula is also the one you'll use to maintain your starter regularly, either at room temperature continuously, or when you take it out of the fridge to rejuvenate it. The only difference is that you'll want to adjust the amounts of water and/or starter up or down when temperatures veer from the norm:

10g whole-rye flour*

10g whole-wheat flour

15-17g water†

2-5g rye starter†

Proof at 70–78˚F (21–25˚C) for 24 hours.

*Or 20g whole-rye flour and no whole-wheat.

†Use less water and/or starter during warmer months if your kitchen is especially warm; use the higher amounts when temperatures are between 65-75˚F (19-24˚C). The culture should expand but not collapse significantly during the proof. If it does, it's a sign you need to slow things down a little.

Refrigerating your rye starter between uses and keeping it active

Like wheat starters, rye starters are amenable to refrigerator storage when not used regularly. The best approach to doing so is to refresh it as normal and move it to the fridge once it has just visibly begun to expand, 4 to 6 hours later, so there’s still gas in the tank before you sock it away.

As with wheat-based starters, they can be stored for a month or more under refrigeration, but the longer they are stored, the more refreshments they’ll likely need to fully revive. To keep it as active as possible, try to give the starter a complete 24-hour refreshment once per week, followed by a second 4 to 6 hour one before returning it to the fridge.

To revive a long-refrigerated rye starter, just refresh it daily until it about doubles in volume in 12 hours or less. After that you can use it in baking and return it to the fridge. (If you bake with your starter, it will get at least one refreshment anyway before you use it, so you won't need to do extra ones unless you want to.)

Rye starters can also be dried down for longer-term storage.

Building a rye sour

All of my 100%-rye formulas include a refreshment stage the morning before the sour is built, but you should give your starter as many refreshments you can if it lives in the fridge most of the time. If the starter is not really active before you use it, the loaf may be very slow to proof (if at all).

Many bakers build their sours at reduced hydrations (around 80%), but I've found that 100%-hydration works just as well, and I find it is easier to judge proof based upon expansion when the sour is on the loose side. When it is ready to use, it should be about doubled in volume, filled with bubbles, and just beginning to recede and break down (much like a rye loaf when it is ready to bake, with cracks and pinholes dotting the surface). There's a window of a few hours for use once it is ready, so long as it doesn't collapse completely.

The goal of a rye sour—like that of a wheat levain—is to activate both the yeast and the bacteria in it. But an equally important one is to build up a lot of acidity, to prevent a phenomenon known as starch attack, where runaway amylase enzymes break down the starches in the dough into sugars during baking, causing the inside of the loaf to collapse and turn gummy. Having a sour that is good and acidic by proofing it fully—and having a lot of it, which is why most good rye formulas contain a large amount of prefermented flour—will largely neutralize amylase enzymes, preventing starch attack.

Flour scalds for ryes

Not many 100%-rye formulas include a flour scald (or "brühstück," in German), but mine do. I like the texture and longevity it gives the bread, and it comes with a fringe benefit: It leaves the dough really warm after mixing. Ryes love being proofed at warm temperatures—85˚F (30˚C) or so—temperatures that are challenging for many to achieve and maintain. When you use near-boiling-temperature water in the final dough, it usually ends up around 95˚F once mixed. While that might be problematic for a wheat dough, it's great for ryes: the yeast gets an immediate burst of energy, and the final proof moves quickly, even if you can't hold it near 85˚F. To avoid the sour and the boiling water making direct contact with one another, I usually bury the sour in the bowl under the flour and other ingredients, and mix everything together quickly, so that the temperature of everything drops immediately. (I also recommend bringing the water to a boil and letting it sit for 5 minutes, off heat, just to let it cool down a bit before using.)

Because some of the flour in the formula is scalded, I increase the total hydration by about 15% over non-scalded ones, to yield a dough of a similar texture.

Going with the flow

A common refrain in rye baking is that a properly hydrated and mixed rye dough should flow. It took me awhile to sort out exactly what this meant, but now I understand it as a dough that is thick and cohesive, but still moves when left to its own devices. Neither loose and liquid like a batter, nor so stiff that it just sits there—like lava (not water). Flow will be especially evident right after you stop mixing or stirring it: it should slump a little, but not flatten out entirely.

If at the end of mixing, your dough doesn't flow at all, add more water a little at a time until it does. If it is loose and sloppy, reduce the water slightly next time (in a pinch, you could add some rye flour to firm it up).

Mixing the final dough

Many rye bakers recommend mixing rye formulas in a stand mixer for around 10 minutes on low speed. I do that too, though I'm not entirely convinced it makes a significant difference in the result. I know other bakers who mix their ryes entirely by hand successfully, and I've done it both ways myself and gotten great results. Many professional bakers who use machines to mix ryes likely do so because it is far more efficient when working with large batches of doughs. It certainly can't hurt to use a mixer, and if it makes your life easier, you should use it, but it's probably not necessary when making only one or two loaves. (I provide instructions for both in the instructions.) Whichever method you use, be sure to wait 10 minutes before assessing your dough for flow and adjusting the hydration, if necessary; you want to leave enough time for the flour to absorb all the water it can.

I've seen it suggested that machine-mixing can increase flow in rye doughs by aerating and lightening them (like whipping air into a cake batter), but doing so with ryes will probably require very long mixing times, on the order of 30 minutes or more (which is never recommended in rye recipes from North American bakers, but is not unheard of in German ones).

As for whether to use a paddle or dough hook to machine-mix, that depends entirely upon the power of your machine. A paddle generally does a better job of mixing the batter-like dough, but if you find your machine struggles or wobbles using it, you may need to use the hook instead.

To hand mix, simply mix everything together with a dough whisk or spatula until uniform, then let the mixture sit for 10 minutes, giving it a thorough stir every other minute or so to fully hydrate the flour.

If the dough includes an inclusion, I usually add it at the very end of the mix, stirring the dough just until it is uniformly incorporated.

Adding baker's yeast to 100%-rye formulas

While sourdough ryes, like wheat ones, are fermented by both yeast and lactic acid bacteria, the bacteria do their most important work—producing acids—in the preferment stage. In the final dough, it is the yeasts' turn to shine. If your starter is active and the dough is warm enough, they'll quickly expand the loaf.

Many bakers suggest optionally adding 0.25-0.33% instant dry yeast to the dough, to boost yeast activity. I don't usually add it to mine, but there's no shame in doing so! You are simply enriching the dough with yeasts, which will ensure you have sufficient lift, especially if the activity of your starter is suspect. Adding yeast will likely shorten the final fermentation time to an hour or so (a good thing, if you are in a rush), so pay close attention to the dough so that it doesn't overproof. Adding yeast can also lighten the texture of the finished bread and reduce sourness, because it gets the loaf ready to bake before the lactic acid bacteria in it have a chance to perk up.

I don’t think instant dry yeast is necessary for ryes, but I do consider it a good “training wheel” approach if you are new to rye baking and not sure whether your starter is ready to do the job on its own.

To bulk ferment or not

Okay, this one remains an open question. Many recipes have you bulk ferment the dough for 20 minutes to an hour before shaping (or scraping the dough into a pan). I've done mine with and without a bulk, I haven't noticed a dramatic difference in the results. (The total fermentation time should be about the same, with or without a bulk fermentation stage.)

Panning the bread

All of my 100%-rye formulas are pan breads, baked in a 9x4x4-inch pullman pan. I like the square, narrow cross section it yields, and it eliminates the need to shape the loaf—you just scrape the sticky dough into a well-greased pan, smooth and flatten it out with a wet dough scraper or spatula.

Some bakers use a wooden press—a flat wooden board slightly smaller than the pan, mounted to a handle—to quickly and easily flatten their panned ryes. If you are handy, you could make your own, but there's an off-the-shelf option that you can find at any good hardware store: a wood concrete float, the tool that masons use to smooth out concrete. I found one that was the perfect width for my pan, and only needed to be cut down in length and given a coating of food-grade oil. Using a press is especially helpful for getting seeds to adhere to the top of the loaf, since you can really press them down into the dough.

Once the loaf is in the pan, most ryes get topped with a solid coating of rye flour (unless they get a coating of something else). Not only does it make for a nice finish on the baked loaf, it helps to make the final proof easy to visualize, since the cracks and pinholes really stand out.

The final fermentation

As I mentioned above, whole-rye doughs love warm temperatures; the recommended final proof temperature is ideally between 82 and 85˚F (28–29˚C). If you can hold the dough within this range, the loaf should be ready to bake within 1 to 3 hours, assuming your starter is good and active, or you are using baker's yeast. If you proof at lower temperatures, it may take an hour or two longer to get there. (If you can't hold the loaf at 85˚F, setting it inside an insulated container will help keep it as warm as possible.)

While expansion is obviously an important marker for readiness, the most important one is the condition of the dough. When a rye is ready for the oven, the dough will just be beginning to break down—the top of the loaf should have a nearly flat (not domed) surface, riddled with cracks, and within the cracks you should see tiny pinholes formed when interior bubbles burst open. The goal is to push the fermentation as far as possible, but not so far that the loaf collapses. Overproofing usually doesn't happen rapidly, so it's fairly easy to avoid if you are checking on the loaf regularly. (If the finished loaf ends up with a depression in the center, it may mean you pushed it a little too far, and should bake the loaf sooner next time.)

If you are new to baking ryes, I’d recommend not topping them with seeds at first, because they make seeing the state of the dough challenging. Even if the recipe contains seeds, coat the loaf with rye flour instead until you have a good sense of how long the final proof will take.

Baking rye sourdoughs

Ryes benefit from steam at the start of baking too, which is another reason I like to use a Pullman pan. Since it has a lid, you can bake the loaf on a bare oven rack and just remove the lid after 20 minutes or so. If you don't have a lidded pan, you can also set the loaf inside a preheated Dutch oven, provided it is large enough; once the steaming phase has ended, remove the pan from the pot and transfer it to the oven rack, so that it doesn't get too dark on the underside.

Most rye bakes start out quite hot—450–475˚F (230–245˚C)—to give maximal lift, followed by a more moderate temperature—400˚F (205˚C)—for the remainder of the bake. I usually drop the temperature when I remove the pan lid.

Ryes are dark by nature, so it can be challenging to use color as a marker for a full bake. After awhile, it becomes second nature, but in the beginning you can use a thermometer to be sure the inside of the loaf is fully cooked. Look for internal temperatures of 205–208˚F (96–97˚C), which usually takes a little more than an hour to achieve.

The waiting game

While rye breads are fast to proof and bake, they can’t be sliced into for 24 hours or so, since the inside will be gummy and soft at first (and the crust leathery and dry). Over time, the starches begin to retrograde and the moisture in the loaf evens out. Once the loaf has cooled to room temperature (after 3 or 4 hours), wrap it in linen or set it inside a paper bag and let it sit at least overnight before cutting into it. (Or at least before cutting into the center of the loaf. I have been known to slice off an end piece while a loaf is still warm, and it is often delicious at that stage.)

Once the loaf has stabilized, you can leave it at room temperature (in plastic or a container) for up to a week, or wrap it tightly in plastic and move it to the fridge for a few weeks. (Ryes don’t stale at fridge temps like wheat breads do, so the fridge is your friend.)

Flying roofs and starch attack: problems with rye breads

Rye sourdoughs have a reputation for being fussy and challenging, which is one reason I put off working with them for so long. There are problems that occur along the way, but in my experience they are easily avoided once you know what to look for. Both relate to enzymes, which whole-rye flour is loaded with.

The first is what the aforementioned starch attack, which is caused by an excess of amylase activity. Amylase is the enzyme that is responsible for the breakdown of starches into simple sugars; its activity is essential to proper fermentation of the dough. During proofing, amylase only acts upon damaged starches (those that have been partially degraded during the milling process); it has no effect on intact starches.

But during baking, intact starches absorb water and gelatinize, rendering them suddenly accessible to amylase. While amylase—like most enzymes—loses activity once temperatures in the loaf exceed a certain point, rye starches gelatinize at a lower temperature than those in wheat. This makes them particularly susceptible to starch attack, which can cause the inside of the loaf to liquify, creating something known as a flying roof, where a large hollow forms just beneath the crust:

Fortunately, amylase works most effectively at relatively high pH levels (between 5.5 and 4.5), so the simplest way to avoid starch attack and a flying roof is to use a large amount of prefermented flour in the final dough (I’ve found 40% to be a safe starting place), and to make sure the preferment is fully-proofed, both of which will ensure the acidity in the dough is high enough.

The other enzyme to fret about is pentosanase, which breaks down pentosans, the starch-like molecules that give rye breads structure in place of gluten. With an excess of pentosanase activity, loaves collapse completely under their own weight, rendering them squat, dense, and gummy.

Unlike amylase, pentosanase likes acidity, and is most active below a pH of 4.0. This means that there is in theory a very narrow window of optimal pH for rye doughs—4.5 to 4.0—during which neither amylase nor pentosanase are overly active. The good news is that runaway pentosanase activity is usually evident before baking—if the loaf collapses before you get it into the oven, it’s a sign it has been overfermented. There’s no recovering from it at that point, but you can reduce the duration of final proof next time around to avoid it happening again.

If your loaf retains its stature and internal texture, but the inside is still dense and gummy (and the top surface settles into a divot after baking), that's probably a sign the dough was over-hydrated and that you should use less water next time, and not an issue with enzymes or fermentation.

I think that’s all I have to say so far on my current whole-rye process. Do you have any questions about it? Hit me up in the comment section.

—Andrew

I love this chapter, and I'll be delighted to buy the book when released. I bake in a professional capacity in France, in a rye-producing region (Auvergne). I'd venture to say that single most important thing with rye baking is getting as good and uncorrected a flour as you can afford, and not changing your flour supplier until you've mastered the basics. Buy T-135 rye to start with, leave the full T-170 experience for later (American non-classified rye flours are too confusing, sorry for this) and do NOT buy any rye flour that is supermarket-related.

Start baking in metal pans, leaving bannetons for the time being, and sprinkle your dough with a small amount of (fresh) yeast. It helps, and I don't know anyone who bakes for a, living around here who skips yeast.

While it's true you kind of need a different baker's brain for rye, once you're a capable wheat baker it will just take a few bakes to get the basics right and enter a totally different dimension.

Mix hot,always bake very hot (260C for the initial 25 minutes or so, then switch your oven off if baking on a thick stone) and don't hesitate to take your loaf out of the pan for the final 20-30 minutes of baking to dry it thoroughly, we always do.

I've loved the chapter and related to 100% of the things said. Looking forward to purchasing the book as said. Thanks again.

I'm going to be baking more rye sourdough this Fall and I plan to refer to this post constantly: thank you for your thoroughness!