Happy Valentine’s Day!

I love Heart Day. My mom is a visual artist, so we always made Valentines together, and the holiday was a time to wear red, be excited, and share heart-shaped treats. Sure, my parents loved each other, but platonic love was our Valentine vibe. In honor of that, I want to share one of my serious loves: research.

As I began my first book, The New Bread Basket, I needed to understand why milling and grain growing left the Northeast. I fell into a lot of bunnyholes, like the fascinating history of baking powder, and the impact of the Erie Canal, but finally I realized I had to write about living people, the ones reviving regional grain production. Luckily, for my current book—about the history of doubting bread in America—I have permission to explore home & professional baking throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Here’s how I do it:

1) Ephemera. I gather paper evidence of the olden days. This started 30+ years ago when I was running a thrift store. On my days off, I’d visit other thrift stores, and I started collecting old food advertising. Fats like Crisco & its competitor Spry were well represented, as was baking powder. I fell in love with the images. Spry had cartoons that were grossly sexist—10 Cakes Husbands Like Best, 12 Pies Husbands Like Best. I studied Royal and Rumford recipes, trying to figure out the difference between corn fritters and corn cakes. I stared at the colorful pictures of cakes as if they were my cakes, prepared for me by a magical aunt and waiting on the counter of a kitchen I just needed to find.

Ephemera lives in antique malls, thrift stores, and on Ebay. I dig for pamphlets and promotional materials because I’m interested in how each food product spoke of itself and of its industry.

There are also antique dealers who specialize in ephemera. I live near a couple who are postal history experts, but they sell general paper goods in their business, A Gatherin. Diane gave me some terrific baking powder treasures, and once helped me decipher a letter with very faded ink.

2) Bibliographies. Books on food history help me understand how changes in agriculture, economics, food-processing technology, and packaging weave into the layered facts of the past. A few great titles are:

Eating History: Thirty Turing Points in the Making of American Cuisine by Andrew Smith.

White Bread: The Social History of the Store Bought Loaf by Aaron Bobrow-Strain.

Perfection Salad: Women and Cooking at the Turn of the Century by Laura Shapiro.

Three Squares: The Invention of American Meal by Abigail Carroll.

Bibliographies are as useful as the text. When I find something I want to learn more about, I chase a citation. For instance, I found the pamphlet, The Story of the Staff of Life, a heady piece of propaganda as bakeries became factories because a sentence in White Bread referred to the 1911 meeting of the American Association of Master Bakers. I found a digitized copy of the meeting’s transcript in Google’s archives. Reading that transcript, I found the organization urging bakers to order copies and suggesting how they use them. Searching for the document, I found it digitized, and a copy for sale online.

3) Libraries. I use the history room at Troy Public Library to get a sense of bakeries in the city directories. City directories are like telephone books that predate the phone, and once it was invented, phone numbers were not the information they delivered. Rather, directories are a listing of residents and businesses. Early editions in Troy blend individuals and enterprises in one long list, so hunting down the bakeries is not simple. But I can stroll through pages and read addresses, and learn who lived there and their occupations. Intermixed are bakeries. By the late 1800s there were separate sections for businesses divided by category, so tracing the arrival and impact of factory bread is simpler.

I use all kinds of libraries. Through my public library, I have a card that lets me get books from the colleges in my area. If I find a title I need that isn’t in my library system, I look it up on WorldCat and see where the nearest copy is. Friday, that meant The Kingdom of Rye by Darra Goldstein; luckily it was available at a college, and I got it out Saturday. The New York State Library is in Albany, just across the river; they have archives that are well worth exploring.

I read trade journals online, either in the vast Google library, or through specific archives at various universities. Sometimes, I get to handle paper copies. Last summer, I spent time with 15 years of bound copies of Northwest Miller & American Baker, a trade journal at Cornell University Library. I had a library cart stacked with the copies, and visited Ithaca a few times to study the way that mills and bakers discussed the arrival of bread slicing and packaging technology. Reading that some bakers thought it was a fad, well, that sentence shimmered like gold.

4) Asking questions. Once I identify a question, I start asking for help. For instance, a few years back, I was trying to see if the recipes for factory bread in Troy in its earliest days resembled modern supermarket bread. In a Facebook group called Bread History and Practice, I asked how I might discover this, and Don Lindgren, owner of Rabelais Books, a rare cookbook specialist, said he’d sold the papers of the Tolley & Ward Baking company to the New York Public Library. These bakeries were not Freihofer’s, my city’s first factory bakery, but the timing lined up, and the collection included notebooks from the first part of the 20th century. He gave me the catalog he’d put together for the collection, which was more detailed than the finding aid—a general index of a library collection to help you navigate. At the end of February, 2020, right before lockdown, I got to spend time with handwritten notebooks from 1906-1908; files filled with recipes written on the back of invoices and other scraps; and more organized company formula books—typed-in duplicates and bound with metal rings.

5) Wandering. I had a chance to roam around New York City last week with my husband. We ate a nice lunch at Veselka, and wandered over to Bonnie Slotnik’s Cookbook Shop. This basement room in the East Village is like a bank. The shelves are lined with my kind of money: cookbooks, and boxes of pamphlets. One drawer is full of premiums that came with flour bags, and I wanted to buy a lot of them, but I settled for one: New and exciting No-Knead breads by Ann Pillsbury, copyright 1945. (As Dayna Evans wrote, this kind of bread did not begin with Mark Bittman & Jim Lahey in the New York Times.) I needed a little evidence of earlier generations of the phenomenon.

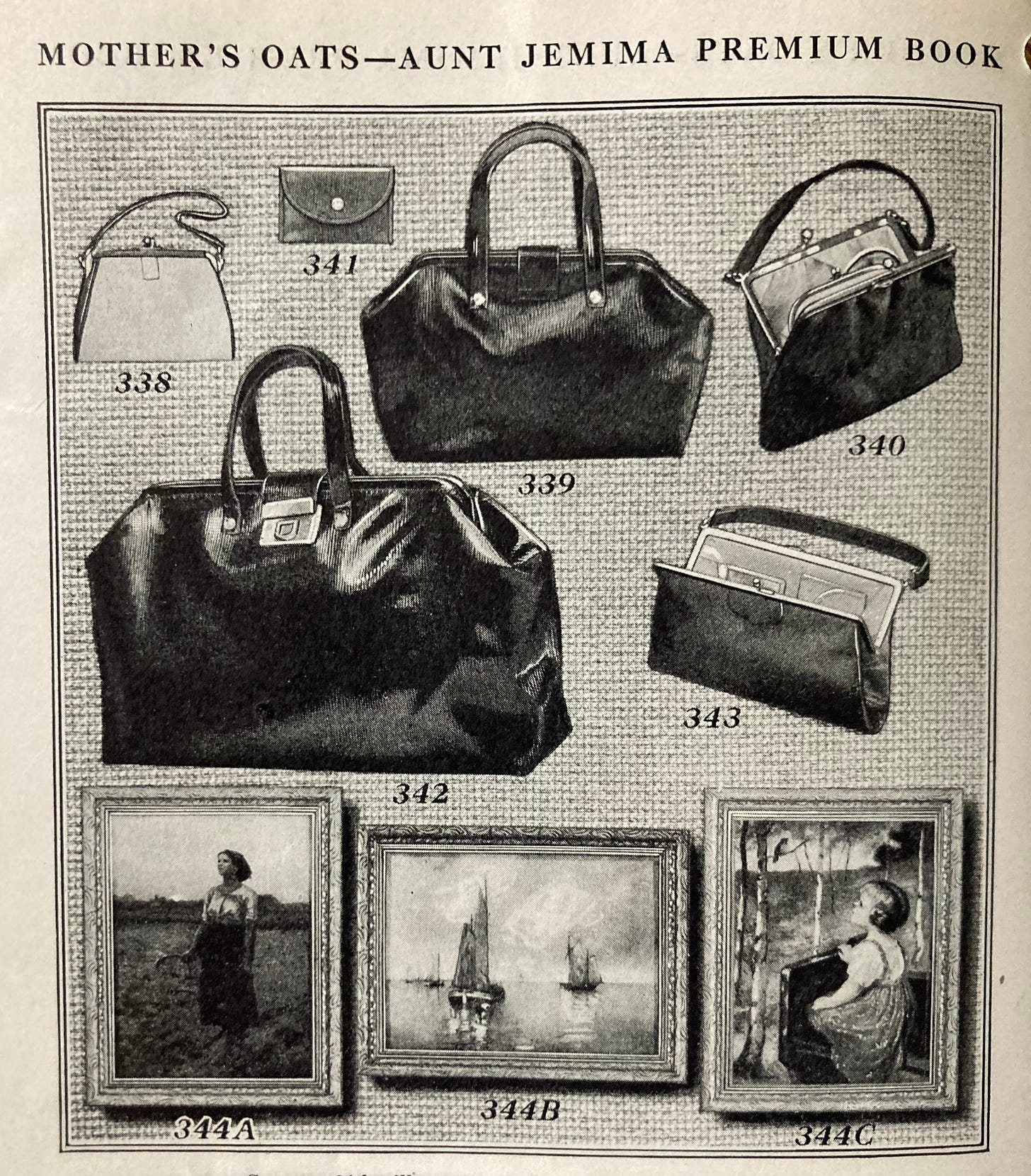

I flipped through a box of booklets on bread, and toyed with getting another version of the Fleischmann’s guide from the 1970s I used growing up, but decided one was enough. I found a 1926 premium booklet for Mother’s Oats and Aunt Jemima Pancake Flour; I had to get that one because I’m really intrigued by Aunt Jemima. Will this be more than something to browse? I’m not sure, but it’s amazing to see that I could have gotten a very early toaster for 205 coupons, or $2 and 5 coupons.

Behind the desk, Bonnie had a few things that were too fragile to put out. As she laid them out, I wanted all of them! Instead I studied them, seeing if they had clues to my continued puzzle: how did professional bakers and flour manufacturers talk about bread and baking from 1900-1920? Here’s what I got, and why:

Bread Recipes & Premium List of the Mahoning Valley Bread Co., New Castle, PA. Quickly, I could see that this pamphlet preaches the gospel of buying bread, and that I needed to have it as a companion to The Story of the Staff of Life. This little book criticizes the housewife for trying to bake bread, when she has no chemist to analyze flour! And her ovens, oh they’re not good. But there’s recipes that use bread and breadcrumbs, and lots of options for what I could have gotten with coupons from their Mity-Nice and Valley Queen breads, like a rough-rider suit, a bread knife, or a catcher’s mitt, and any of these purses and pictures.

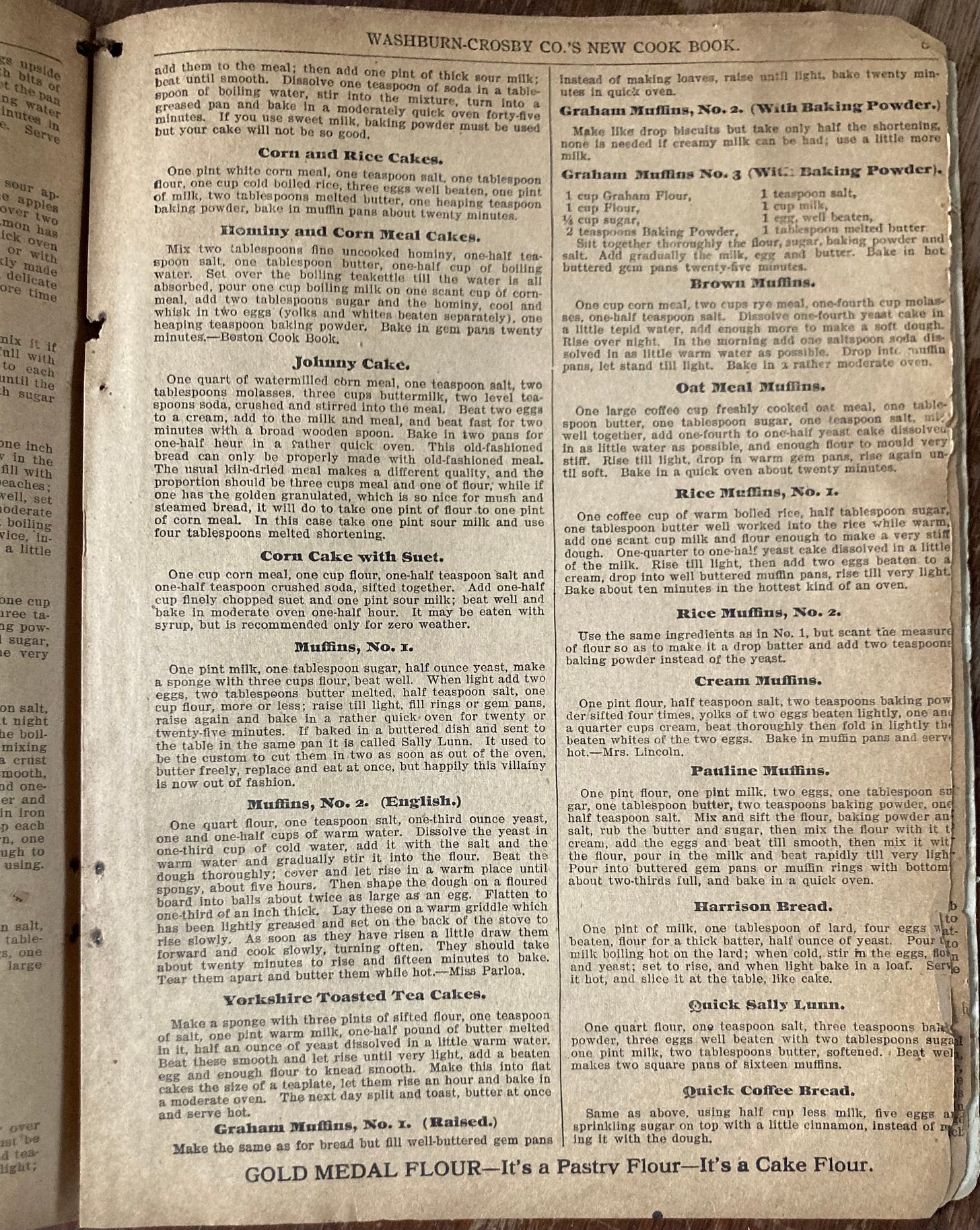

Another easy yes was a Gold Medal Cook Book from 1904. This I got for the flour ads, lush with Gibson girls ordering fine flour on a telephone, and dapper men moving flour barrels. At the bottom of each page, Gold Medal Flour is called a biscuit flour, bread flour, pastry, and cake flour! The bread pages have good information about the ways people made bread, and what quick breads they made—brown muffins had cornmeal and rye, my favorite flour combo. The reader is encouraged to read the article on white bread on page 70, which argues that white and wheat bread are equivalent in nutrition.

A Treatise on Flour, Yeast, Fermentation and Baking by Julius Emil Wihlfahrt, 1914. I’ve glanced at copies of this online, and was eager to have a copy of this Fleischmann’s cookbook to hold. This is a book for professional bakers, and gives me a good sense of bakers’ concerns: understanding leavening, the effects of mixers, ovens, and flour differences. The voice seems more the author’s than the sponsor’s, and offers lots of solid practical information. Advertising was not the aim, as I’ve seen in Fleischmann’s booklets geared to home bakers. The primary goal of this book was to be a resource for modernizing bakeries.

So that is my lovely haul, offered to you this loving day.

Love this dispatch, as a fellow bread researcher rabbit hole diver. Bibliographies truly make me giddy. So many places to go - how do you prioritize your time?? Can’t wait to read your new book, Amy :)

A bread nerd’s delight! Fun.