The Desk Dispatch: In Diaspora, Spice Becomes Seed

Ruby Saha follows the thread of mahleb through an Eastern Orthodox baking tradition.

It was an email from Ruby Saha that inspired me to follow through on my idea to start The Desk Dispatch. She wrote me a kind note, and I realized that the best thing I could do for young writers was create a new space where they could have their work edited, seen, and compensated. In today’s Dispatch, her interest in diasporic traditions leads her to two bakers of Armenian descent who use a fragrant spice to stay connected to and rooted in their ancestry. It seems significant to note that Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day is this Wednesday, April 24.

Saha is a writer and fundraiser based in Chicago. Born and raised in Southeast Asia to Bengali parents, she writes long-form essays about food, culture, climate, and colonialism through the lens of diaspora and cross-cultural connection. You can read more of her work in her newsletter, roots & seeds, which just launched this weekend.

In Diaspora, Spice Becomes Seed

By Ruby Saha

Braids of sweet leavened bread thread together the springtime traditions of Eastern Orthodox communities. Come Easter, Orthodox homes fill with the scent of cherry-fragrant almond and tables laden with dyed eggs and braided loaves. Three strands represent the Holy Trinity; the risen dough celebrates Christ’s divine resurrection.

Each culture has its names and variations for this bread, but the essentials are the same: a yeasted dough not unlike brioche, enriched generously with butter, eggs, sugar, milk, and spice to break the Lenten fast. Armenians sprinkle their choreg with nigella and sesame seeds, while Greeks season their tsoureki with mastiha, the chewy resin of a tree native to the island of Chios. In Assyrian traditions, their iklice breads are made in Mardin, a city in southeastern Turkey, with the addition of ginger, cinnamon, aniseed, and pepper to reflect the city’s history as an ancient Silk Road hub. And threaded through them all is the marzipan flavor of mahleb, a subtly floral spice used by cultures across the Mediterranean.

Mahleb, also known as mahaleb in Arabic, mahlep in Turkish, and mahlepi in Greek, is the tiny bead-shaped kernel of the Prunus mahaleb, a sour cherry. It is endemic to the shores of the Mediterranean, Black, and Caspian seas, where three continents conjoin; mahleb is most often sourced from Iran, as well as Turkey, Syria, and Lebanon.

Across Orthodox communities, whose ancient traditions closely reflect pre-Christian rites of celebration and connection with the natural world, cherries are harbingers of seasonal change and abundance. Mahleb cherry trees bloom as the frost thaws and ripen as the days get long; the sight of dark cherries at the market is the surest sign of summer. Too sour to be enjoyed raw, mahleb cherries are picked and pitted when ripe; some cultures preserve the fruit in liqueurs. The pits are dried and cracked open to extract the bitter aromatic seed, sold whole or finely ground for baking.

“It's like vanilla, almond, cherry, and a little floral, cherry blossom–y kind of vibe,” says Kat Talo, a baker of Armenian heritage who runs a microbakery in Chicago called Butter Bird. “At low doses, it keeps that really fragrant scent and flavor. But if you put a little too much in, it starts getting bitter,” which Talo personally enjoys. “I can’t really think of anything else that tastes like it.”

Despite growing at the nexus of early human trade and appearing in sweet dishes and ointments throughout the region since ancient times, mahleb hasn’t become commonplace far beyond its roots; it remains elusive and exclusive to diaspora shops and high-end spice suppliers like Curio and Spice Trekkers. This might be partly owed to its volatility: like flax seeds, mahleb’s fragrant oils turn rancid quickly, and it’s best kept whole in the freezer and ground for use as needed.

For Lusi Icliyurek, an Armenian baker living in New Jersey, the scent of mahleb evokes her childhood in Istanbul baking choreg and koulourakia with her grandmother.

“On Thursday [before Easter Sunday], we bake bread and dye eggs. It’s a big thing in the house, everyone together, my grandmother dyeing the eggs with onion skin. We were doing it all day long,” she explains. “For me, it's the tradition. It’s my grandmother's and grandfather's tradition, my childhood tradition.”

Making choreg is hard work. The egg-rich dough is unforgiving and requires strength to knead and twist into submission. And it’s always made in large quantities.

“For Easter, when you make choreg, you make a lot,” says Icliyurek. “The tradition is not to make it to eat yourself. You bake choreg, a couple [dyed] eggs, make a nice package, and give it to all your neighbours, all your friends. Everybody gives it to each other.”

Talo, too, remembers baking choreg with her grandmother Elaine over Easters and Christmases in Michigan. A German from a Midwestern farming family, Elaine met Harry, Talo’s Armenian grandfather, in college. They lived in Detroit, where Elaine was welcomed into Harry’s Armenian church community.

“They called them ‘odars,’ outsiders,” Talo says. “But they didn’t treat her like that. I think they understood the feeling of it, you know, being oppressed for who they were.” Elaine learned to make choreg and other Armenian recipes from the church women and from Harry’s mother, a survivor of the Armenian genocide.

“Without a shared language, she learned alongside them, learned recipes that she taught my mother, taught me,” she says. Talo, whose one-year-old is named after her great aunt Sona, another survivor, hopes to pass them on to her daughter, too. “I think, because we lost so many people, they were like, If you’re here, you’re family.”

For diaspora communities like Armenians, whose identity is defined by the experience of forced displacement and ethnic cleansing, the celebration of Easter, of rebirth and abundance, holds the added weight of existential survival—of people, culture, history, identity. As the Ottoman Empire sought to consolidate its territories in the wake of military defeat, separatist nationalism, and anti-imperialist movements, Orthodox Christians across Anatolia were rounded up, expelled from their ancestral homelands, and systematically eliminated through pogroms and death marches. It’s estimated that over a million Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians were killed between the 1910s and 20s, functionally erasing two thousand years of Orthodox Christian civilization in eastern Anatolia.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, there were 2.5 million Armenians residing in Anatolia. By 1922, that number had shrunk to 400,000. Today, just over 60,000 remain.

“When you live in a country where you are two percent [of the population], being connected to your roots is very, very important,” says Icliyurek, speaking of her experience growing up in Istanbul, where the majority of surviving Armenians in Turkey are concentrated. “What you have is your religion, your community, your language. That’s it.”

Most survivors of the genocide were displaced around the world, forming a diaspora that stretches from Syria to Singapore. Many fled to Europe before making the long trek to the United States, where large settlements formed primarily in California, the Northeast, and the Midwest. Talo’s great-grandparents arrived in Detroit via Cuba, while Icliyurek’s family is scattered across Turkey, Greece, France, the United States, and Mexico.

Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day is held annually on April 24. But formal recognition of the genocide remains contested. As of 2023, only 34 countries have issued formal recognition. In 2021, President Joe Biden became the first American president to release a statement acknowledging the mass deportations and killings. The Republic of Turkey is steadfast in its denial, calling it the “Armenian Allegation of Genocide.”

In recent months, the world has proven again how quickly people will dismiss the word “genocide” as too extreme. But when nothing remains but people, every fragment of remembrance is precious, even the point of severance. The denial of genocide “challenge[s] and undermine[s] the memories of the survivors and the claims of their descendants, both from the remnant communities in Turkey, and the multilayered, widely dispersed Armenian diaspora” (Kasbarian, 2017). It is “the final stage of genocide” (Stanton, 1996).

Diasporic identities are built upon remembered and re-enacted practices of food, tradition, community, and faith. “For descendants of survivors… choreg is the cornerstone of their identity, made generation after generation during Easter in the houses they grew up in, intertwined with the most significant childhood memories they had,” writes Liana Aghajanian, a journalist documenting the experience of Armenian-Americans like herself through her project, Dining in Diaspora. “When circumstances beyond their control have caused the disintegration of families, lineage and identity, food has remained the last cultural remnant of historically oppressed people who have lost so much.”

I’m not Armenian, but I’ve spent my life exploring how food connects us to a sense of place, of belonging, of being. I’m Indian, but I was born and raised in Southeast Asia. My parents trace their roots to both sides of Bengal, a land and people torn apart by the dissolution of the British Raj in 1947. My father’s family was among the two million Bengali Hindus displaced from eastern Bengal, now Bangladesh. After the Partition, my great-grandfather never saw his homeland again.

For displaced peoples, there’s something almost otherworldly about being rooted to a place. Not just the idea of it conjured up in memories and old photos, but living roots buried in sun-warmed earth you can grasp with your fingers. When identity is defined by survival—of genocide, colonization, displacement—lineage is more than just a tree. It’s blood that still runs, in defiance of the oppressor. It’s a smuggled sapling with trace evidence of the homeland clasped within its roots.

For Orthodox diaspora communities, then, mahleb is more than just a spice. It’s the seed of a tree with roots in a long-lost ancestral home, a connective thread when all others have been slashed. It’s a bridge between memory and survival, held together with braided knots of leavened bread.

Severed from the cycles of the homeland, the observance of seasonal rituals like braiding bread is transformative, a relentless revival of cultural heritage. The tree still grows in the earth your ancestors once walked, its seeds blooming in new geographies. The bread still rises, like Jesus from the tomb. It’s survival. It’s rebirth.

Next Monday I send out The Desk Digest, a compendium of all of April’s posts. I’ll return with a fresh essay on Monday, May 6.

Paid Subscriber Notes

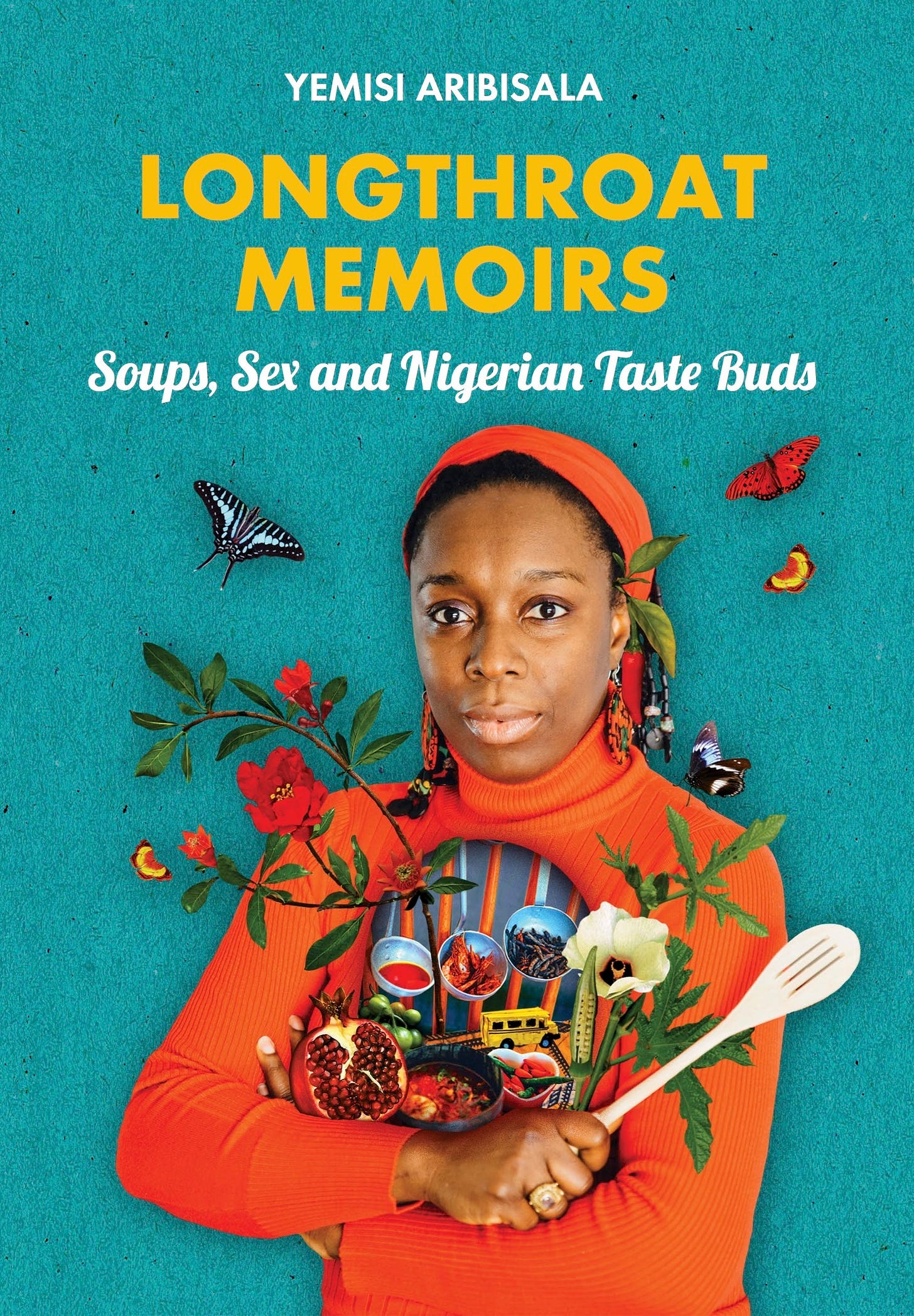

The Desk Book Club is currently reading Longthroat Memoirs: Soups, Sex and Nigerian Taste Buds by Yemisi Aribisala. The first discussion thread will take place on May 31. Buy it from Archestratus for 20 percent off!

If you’re looking for cooking inspiration, remember to scroll through The Desk Cookbook.

Each The Desk Dispatch contributor is paid $500 thanks to subscribers. I so appreciate getting to have this ad-free space for essays and cultural criticism in food. If you’d like to make this sustainable and perhaps enable it to expand in the future, please consider upgrading your subscription to paid.

News

My book No Meat Required: The Cultural History and Culinary Future of Plant-Based Eating will be out in paperback on June 25. Consider it a nice lightweight beach read!

Reading

The Coloniality of Modern Taste: A Critique of Gastronomic Thought by Zilkia Janer