Sakadane: Where Koji Meets Bread

A guest post from fermentation expert Kirsten K. Shockey

Table of Contents

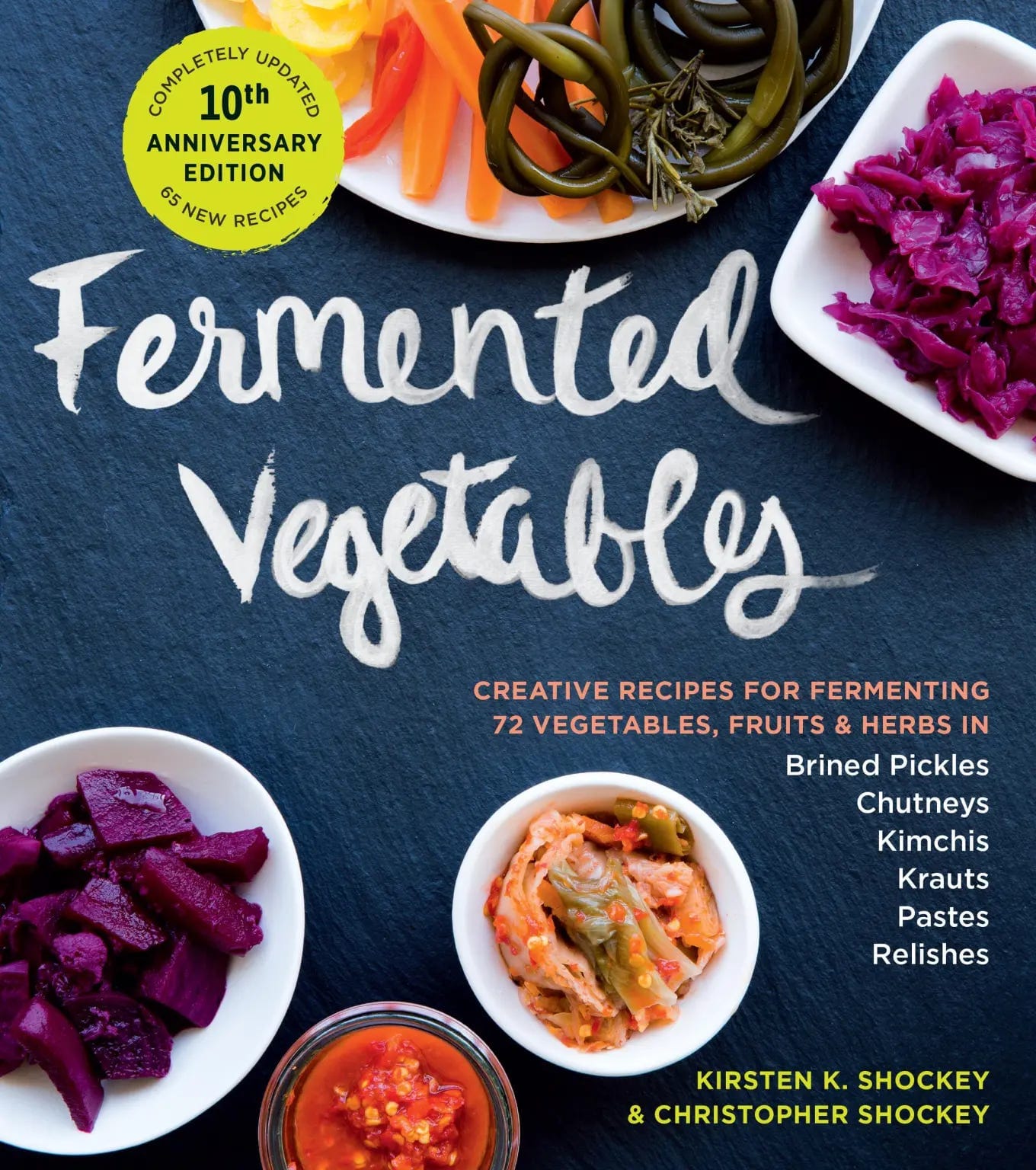

Today we have a guest post from Kirsten K. Shockey, the co-author of—with her partner Christopher Shockey—the books The Big Book of Cidermaking, Fiery Ferments, Fermented Vegetables, and Miso, Tempeh, Natto and other Tasty Ferments, and the author of Homebrewed Vinegar.

A fully-updated, 10th-anniversary edition of Fermented Vegetables was published by Storey Publishing in April, and it’s an amazing guide to transforming and preserving just about any vegetable, fruit, or herb you can think of. Kirsten has a newsletter of her own, Fermenting Change, which I highly recommend for anyone interested in fermented foods.

She and her books are essential resources for all things fermented, and I couldn’t be more excited to share her work and expertise here. Especially since she mentioned she wanted to write about a recent visit she made to a bakery in Japan working with sakadane, a traditional natural ferment that uses sake yeast, not sourdough, to leaven their breads. It’s a very cool process, one that she’s inspired me to experiment with myself. It’s surprisingly easy to create a sakadane culture from scratch, and it makes amazing and long-keeping breads. (I’ll be sharing more about my own experiences with it in next week’s post.)

—Andrew

I’m Kirsten Shockey and I ferment things. I’m delighted to do a guest post here, especially since I have to admit I am not the baker in our family—my partner Christopher bakes, I enjoy! I do, however, work with koji, yeast, and just about every other ferment imaginable so I feel comfortable as your tour guide today. (Do come visit me at , where I tell stories about life—all life. While I focus on microbes and food, you might also find yourself visiting a salt pan or beaver pond with me.)

You are all familiar with sourdough, but have you heard of using koji as a starter for a bread dough? If you aren’t familiar with koji, it is the Japanese word for Aspergillus oryzae, a filamentous fungus, or culinary mold, that is now widely used around the world to unlock flavor with the power of enzymes.

A traditional method of growing koji begins with steaming rice, barley, or soybeans and inoculating with koji spores so that it will grow on the surface of the offered substrate. The inoculated substrate is then kept warm (around 90°F/32°C) for the next 40 hours (give or take) until the koji mold has covered the surface of each grain. When koji takes up residence on a surface it produces and lays down a complete set of enzymes (of which it has over 50 different enzymes) to break things down. All this to feed itself and in turn help us feed ourselves. This type of fermentation is called autolysis, which is just the fancy way to say enzymatic breakdown. As bread bakers you are familiar with this. You may have used recipes that use autolysis (also written autolyse) in which the flour and water are mixed together and allowed to rest. Naturally occurring enzymes break down the gluten by splitting up the proteins. With koji we have this extra rich enzyme soup that we can add to any substrate to quickly get to the sugars and protein to get the next fermentation off to a great (delicious) start.

Humans and koji have been collaborating for thousands of years. Koji’s history and use are deeply rooted in Asia; the first mention of using mold to transform food was made in 300 BCE, during China’s Zhou dynasty. An even earlier analysis of Neolithic pottery from the second millennium BCE revealed residue of rice-based fermented wine. The discovery and subsequent domestication of Aspergillus oryzae unlocked the nutrition and flavor potential of soybeans and grains.

Koji is all about using the power of enzymes to snip apart the large (and mostly flavorless) molecules of starches, fats, and proteins, transforming them into flavorful sugars, fatty acids, and amino acids. The history continues as Aspergillus oryzae traveled with monks or traders throughout Asia. If you think of koji as the trunk of a tree, then each of its many uses are the branches reaching to the sky in their own directions. Traditionally, these were rice wines and spirits, douchi (black bean paste), vinegar, miso, and soy sauce. In modern kitchens across the planet there is no limit to the way people are harnessing its power.

The worldwide koji community is linked by threads that connect friends to friends creating a network of communication very much like mycelium does beneath the soil. Let me explain. Like those strands of unseen mycelium, the story of koji sourdough I wish to tell is linked by individual relationships with koji—it is the human connections after all that allow us to share the the wonderful work people are doing in collaboration with microbes.

Midori Uehara is a fairly close neighbor in the way a bird might fly through these conifer-wooded mountains of southwestern Oregon, as in just over a ridge or two. By car, she’s an hour and change away. We met a few years ago through miso—Midori is our local miso maker—and quickly became friends. When she learned we were headed to Japan, she scheduled a trip to visit her family at the same time, so that we could visit fermented-food makers together.

Midori met second-generation baker and owner of Miki Natural Bread, Kazuki Araki, online through her friend Yoko. Yoko lives in Los Angeles and is a fellow student in Koji School, an online school and community of around 500 students strong and was founded by Nakaji Minami Tomoyuki—expert koji maker, food culture designer, and author of the book Koji for Life. Yoko and Araki-san had met through a mutual Japanese friend who lives in New York and used to be in Koji School. See, like mycelium, koji truly does unite.

Today’s excursion began in late March on our second-to-last day in Japan. Midori arranged the day with Araki-san. It included a visit to his bakery and a tour of natto production (a story for another day). Araki-san picked us up from the train station, and immediately passed us each a cup and offered thermoses of hot rooibos tea or coffee. Then he offered us onigiri he’d made in case we were hungry. He then took us to his bakery in Kamisato, Saitama Prefecture.

When we walked into the bakery, Midori and I both inhaled deeply, taking in the perfume of freshly-baked bread laced with a light extra sweetness—koji maybe? Araki-san asked us what we smelled, and I immediately thought it was a test. It wasn’t, he was simply curious because he said he is so accustomed to the scent that he doesn’t smell the nuance anymore.

Employees were packaging sliced bread, cinnamon buns, and focaccia. We walked through the baking area; baking was finished for the day but the ovens still radiated some latent heat adding to the atmosphere of steamy freshness. We stopped quickly in a room that held hundreds of beautiful cooling loaves. Araki-san said that every one of the loaves would become panko, the light, flaky Japanese breadcrumbs typically used for coating deep-fried foods.

But we were headed beyond, to a cool, quiet space to visit the fermenting buckets of sakadane, koji sourdough starter. As we moved quickly through the empty baking area Araki-san asked if we drink sake; we both said we did.

He opened a door to the fermenting room and rolled out a bucket that had been fermenting for 5 weeks. The starter at this point is basically a doburoko—a cloudy, homestyle sake that has a 14–16% alcohol content. It was sweet and fragrant. The fermented rice covered the culture with a still, thick, and cracked cap. As soon as Araki-san gave it a stir, bubbles rose from the watery lower layer and through the mash, excitedly filling the air with the scent of floral sweetness and yeast.

This sakadane is the yeast that brings the lightest of textures and perfection of crumb to every one of Miki’s products—around fifty baked goods, from croissants and pastries to rich breads and panko. Araki-san said that before World War II, bakeries all over Japan made bread using yeast derived from koji. Unfortunately, he said, it was gradually replaced by industrially-cultured yeast from America, and now there are only three bakeries using sakadane in the entire country, including him. As far as he knows, there is one person in Shimane Prefecture and another in Tokyo who makes bread professionally using sakadane. Currently, however, there are about five teachers who teach classes where you can learn to make bread at home using yeast derived from rice koji; this is renewing interest in the process.

(There is also a dry yeast that is developed from sake-brewing methods called Hoshino yeast, which I believe is used more widely. I am told it smells sweet and pleasant—as most things koji do. While it has a similar process and catalyst—koji—in its making, it is like comparing active dry yeast to a sourdough starter. From the process to the end product, things will be different.)

When the sakadane is ready—sweet, yeasty, and alcoholic—it is added to wheat flour and water and allowed to ferment for 15 hours to create the sponge, or levain. Araki-san’s bucket contained around 16 liters of sakadane; to it he added 60 kg of flour and 50 kg water. After the preferment is ready, they then add more wheat flour, water, and salt as it is being mixed with a dough hook to get the proper dough consistency. The dough is then proofed depending on the recipe. For example, Araki-san said, it proofs for 3 to 3-½ hours for a sourdough and only a single hour for their French-style loaves like baguettes, or one of their panko varieties.

Three generations work side-by-side at Miki Natural Bread. Araki-san’s father, the bakery’s founder, still makes dobruko for the sakadane, and the bakery still uses his original recipes. His son, who has been interested in baking since he was a child, spent four years studying bread baking in Germany, and has developed a recipe for the shop.

These days Araki-san himself is most involved in growing the koji. He explained that he is experimenting with altering the ratio of protease and amylase enzymes produced by the process. For the wheat-based products they make now, he is interested in promoting amylase’s saccharifying enzymes, and not protease, which will break down the gluten.

To get his koji on point he usually grows it in a drier environment than, for example, a miso maker might. He also grows it slowly: the batch starts at 8 am on Thursday, then finishes Saturday around noon for most of his bread. He doesn’t want the outward growth of fuzzy koji rice, instead, he wants the koji to work on the interior of the grains. This, he explained, produces more amylase and reduces the amount of protease. As soon as it is done they start the process of making the sakadane by adding freshly steamed white rice and water.

Araki-san told us that in the last 10 years, gluten intolerance in Japan has grown from 1 in 100 to 1 in 50; if one accounts for the people who are avoiding gluten for other reasons, the number becomes 1 in 20. He has developed one gluten-free rice bread so far, and is very interested in eventually having many of their products available as gluten-free. This changes how he grows the koji for the starter. For the rice bread, the protease is welcome, as it breaks the tiny bit of protein in the rice and it creates stickiness so that rice flour loaves can rise.

For the gluten-free starter, he doesn’t use the koji fresh. Instead, this koji is first dehydrated in the incubator at 40˚C for another 18 hours, for a total of 70 hours, to encourage it to produce protease. To begin the sakadane starter he first must rehydrate it.

Araki-san is also one of a few people pushing this art further. He told us, “My research focuses on yeast and enzymes derived from rice koji that break down wheat starch. My latest research project involves a joint study of how rice koji enzymes break down rice flour, improving its suitability for bread making. I also proposed a hypothesis about the effect of rice flour on protein breakdown, which my collaborators verified by measuring the results. There are many cases where I cannot prove my hypothesis, so I keep repeating the process.”

I hope someday I will have a chance to see (taste) the results. From the sample I had of his 100-percent rice bread, I can say he is headed down a special path. It is delicious and the texture is light, with none of the sandiness one has grown used to tasting in a gluten-free loaf. I am hoping to work with this technique (ok, if I am being honest, encourage Christopher to use the starter I make) this winter. Do drop me—or Andrew—a note if you try this out.

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.