Lifestyles of the Enriched and Famous, Part One

On enriched breads and their ingredients—Eggs

Table of Contents

Lately I have been working on the remaining enriched breads for my book and thought it would be a good time to write a little about them here. I probably have far too many recipes to fit into the book at this point, but I’m hoping to cover both “classic” formulas (brioche, shokupan, challah, etc.) and all the alternative ways you can squish-up a bread, including using cooked starchy vegetables like potato, sweet potato, and squash. (These are among the ones I am fiddling with now.)

Though one common definition of “enrich” means to make a food more nutritious (as in enriched flour), in this case it means quite the opposite: Enriched breads are those that include large amounts of less-than-healthful ingredients that make the loaf more luxurious and posh—butter, oil, sugars, eggs, milk, etc. They also make the bread significantly more expensive to produce, since each of these ingredients is far more costly than flour, water, or salt.

The type specimen for enriched breads is brioche, which is extra in all ways: high in sugar (10-20%), butter (from around 30% to as much as 100%), whole eggs and/or egg yolks (50% and up), and milk (or even cream) in place of water. (The word brioche has more modest origins than its current composition would suggest: it is apparently derived from broyer, which refers to a wooden rolling pin used for kneading dough, a “broye”.)

At the other end of the spectrum, you have more modestly-enriched breads like pain de mie or shokupan (or my mashup of the two, shokupain de mie), which contain milk in place of the water, 5-15% butter, and, in some cases, 5-10% whole egg or egg yolk.

Each of the ingredients used in enriched breads alters the texture typical in leaner doughs, which is their main point: where lean breads are crispy, chewy, and often short-lived, enriched ones are soft, tender, and (often, though not always) long-keeping. These effects are achieved by lessening the ability of strong gluten networks to form, but obviously that comes with a cost of extra effort to achieve enough structure to support an open crumb and a tall stature. This is especially true for brioche with its extreme amounts of butter, for which most bakers work hard to develop a lot of dough strength before adding the butter at the end of mixing. (Not me, but I’ll save that discussion for another day.)

Over the next month or so, I’ll be exploring each of the ingredients that go into enriched breads (including my current thinking on reliable vegan substitutes for each), starting with eggs, without which many enriched breads would not be possible to make.

The incredible, edible egg

Many of the ingredients used in bread baking are pretty simple. Water, salt, and sugar are composed of single small molecules, and most fats contain just a handful at most. Flour, meanwhile, contains a wide array of compounds—starch, proteins (including gluten-forming ones and enzymes), fats, sugars, fiber, vitamins, minerals, and water.

After flour, eggs are maybe the most complex ingredient used in bread baking. Whole eggs contain about 76% water, but the remainder includes more than a dozen different proteins, several kinds of fats (and fat-protein complexes), cholesterol, lecithin, sugars, minerals, and vitamins. The most important contributions to bread that eggs supply are increased browning, tenderness, richness, and structure.

Unlike flour, which can be sifted, but is otherwise indivisible, eggs can be easily separated into two very different mixtures of compounds—whites and yolks.

Egg whites

Egg whites are ~90% water, with the remaining 10% mostly being proteins. Whites have little in the way of flavor, at least in a bread; their proteins help promote Maillard browning in the crust, and they firm up during baking to give the bread structure. But egg white proteins bind water tightly when heated—think meringues—so whole eggs and egg whites can leave a bread dry and firm if not used judiciously. Because of the drying effect of egg whites, like many bakers, I prefer to use a mixture of whole eggs and yolks in brioche and other eggy breads, rather than whole eggs alone. (Or just yolks alone, in the case of less-enriched formulas.)

Though whole eggs are mostly water, the water is somewhat bound up within their proteins, even when raw. This can make hydration of dried yeast slow to happen when most of the water in a dough comes via eggs, as in brioche. (You can often see the undissolved granules in the dough after mixing.) It will eventually hydrate, but it can cause problems with fermentation. For this reason, I always recommend hydrating dried yeast in twice its weight of water (or mixing it with the remaining milk or water in the formula, if there is any) before using it in a very eggy dough, to ensure it is hydrated ahead of time.

Egg yolks

Egg yolks are ~50% water, along with 35% fat and 15% protein. Yolks supply flavor, color, tenderness, and richness to breads. Yolk proteins firm up when heated too, but not nearly as much as those in whites (which is why you can make an egg-white omelet, but not an egg-yolk one). Egg yolks are high in amylase, the same enzyme found in flour responsible for the conversion of starches into simple sugars, so whole egg and egg yolk can increase the rate of fermentation (and increase browning in an indirect way).

But maybe the most important and least appreciated component of egg yolks in bread baking is the phospholipid lecithin, which accounts for some 10% of their weight. Lecithin and other phospholipids are powerful emulsifiers, molecules that can co-mingle with both fats and water equally well, and, more importantly, make them get along with one another.

Egg yolk's power as an emulsifier is best known in the context of mayonnaise, where it turns normally-antagonistic oil and water into an harmonious, velvety sauce, but it functions identically in enriched breads too. Without the emulsion-stabilizing properties of egg yolks (or some other source of lecithin) brioche would be an impossibility—only with the yolks’ lecithin can all that butter blend into the dough easily, and the dough rise nearly as tall as one with far less fat in it.

(By the by, someday I’ll talk about the use of small egg yolks in non-traditional contexts, as I have been experimenting with lately, things like focaccia…)

Vegan egg yolk substitues

I’m still working on my vegan brioche and other enriched breads formulas, in part because I haven’t yet found a good “natural” source of lecithin to emulsify the fat. Many foods are rich in lecithin (sunflower and sesame oils, especially), but none quite as much as egg yolk, and I’ve yet to find another food you can buy at the supermarket that works well enough.

Purified lecithin is available in many stores, however, either in liquid or powdered form, usually in the supplements aisle. Liquid lecithin is very viscous, even more so than molasses, which makes it challenging to work with, especially in small, home-baker quantities. Powdered lecithin granules are much easier to scale out and mix with other ingredients, and are my preference. (I use them to make my own nonstick pan release, something you’ll need for enriched bread baking too, so lecithin is useful even if you aren’t doing vegan baking.)

One egg yolk contains about 1.7g of lecithin, but a little more lecithin probably cannot hurt, so I use 2g lecithin as a single-yolk equivalent. (I’ll go into vegan enriched breads baking again once I nail down my own formulas.)

Egg sizes, weights, and scaling eggs

Eggs are unique as bread ingredients in another way: they come in individually-packaged units of a specific weight and are annoying to divide. For this reason, I tend to craft my recipes around whole-egg (or whole-yolk) amounts, to minimize waste and hassle. And, like most baking recipe writers, I use large eggs, for consistency.

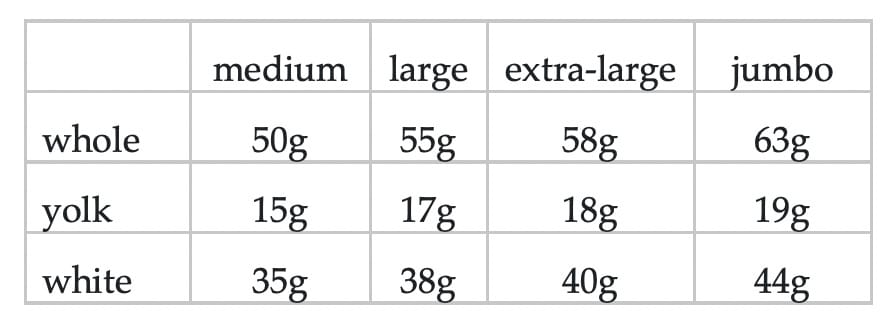

In case you happen to use other sizes of eggs, here’s a chart you can use to determine how much you’ll get out of each of them. I’ve revised the numbers I used in my Pocket Companion because US egg weights seem to have crept up in recent years.

In any case, these numbers are averages, and while the average large egg should weigh about 55g and a yolk about 17g, in truth they often don't. So when I’m scaling out whole eggs for a recipe, I'll crack the eggs into a bowl and weigh them, without breaking the yolks. If the mixture weighs more than needed, I'll pour off a little of the white to bring it down to the appropriate weight. If it is slightly under weight, I'll make up the difference with a little water or milk, rather than crack another egg for a few measly grams of white.

When it comes to yolks, I’ll just scale out the appropriate number of yolks, free of as much white as possible, and not worry about whether their weights are exact, since the variance will be insignificant.

Substituting eggs, egg whites, and egg yolks for water in formulas (and vice versa)

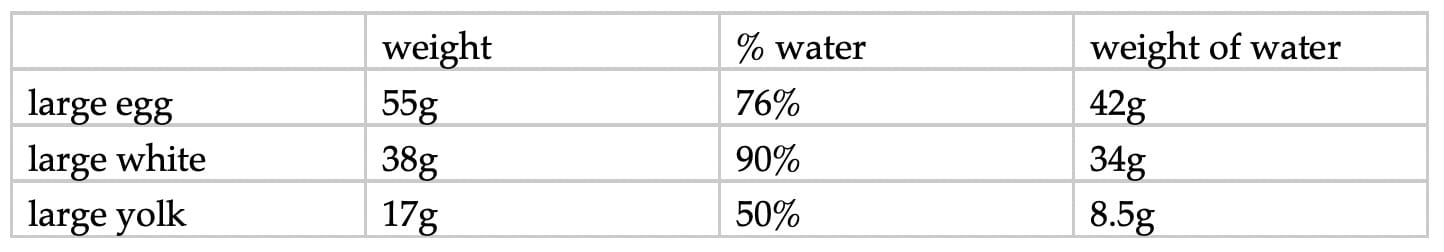

If I am adding whole eggs to a formula that doesn’t have them, I adjust the hydration of the dough to achieve a similar consistency, based upon the amount of water in the eggs, using this chart:

For example, if I add two large eggs to a formula, I’ll reduce the water in the dough by 84g (2 x 42g). If I am removing an egg, white, or yolk from a formula instead, I’ll simply add back the amount of water it contained. Eggs and yolks contain solids and fats that will alter the texture of the dough too, so this isn’t a perfect approach, but it gets you in the ballpark. It is usually easy enough to dial in the hydration after a test or two.

Anyone have any other thoughts or questions about eggs in enriched breads?

—Andrew

wordloaf Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.