Hello from the Wordloaf Friday Bread Basket, a weekly roundup of links and items relating to bread, baking, and grain.

Extracted

Vanilla is dismissed as a quotidian, humdrum spice, despite the fact that it is one of the most-used, most important, and costliest flavorings in our foods and beverages. And despite the fact that vanilla is incredibly painstaking and time-consuming to produce: The hand-pollinated fruits—pods, not “beans”—remain on the plant for nine months before they are ready to harvest, and even then must be fermented and dried for use in cooking. I treasure vanilla, and all the more so now that I have read Ruby Robina Saha’s recent story on the aromatic spice and how it makes its way into our cabinets:

It’s truly wild to me how vanilla remains anonymous in our cultural understanding of food. We speak of it as plain, bland, boring, basic; the absence of flavour and excitement; a shorthand for quotidian sex.

This linguistic sleight of hand allows us to ignore the complexities and injustices bound up in vanilla production. This ignorance extends to so much of our food system, which depends upon the invisible labour of communities most vulnerable to the twin shocks of climate disaster and market volatility, where the difficult realities of agriculture are wilfully obscured by marketing and convenience.

To speak of vanilla is to speak of power. Who has the power to set its price, to determine its value? Who gets to enjoy it? When we reach for that bottle of extract, we're grasping the end of a long chain of labour, exploitation, and environmental impact.

my dreams, my works, must wait till after hell

I hold my honey and I store my bread

In little jars and cabinets of my will.

I label clearly, and each latch and lid

I bid, Be firm till I return from hell.

I am very hungry. I am incomplete.

And none can tell when I may dine again.

No man can give me any word but Wait,

The puny light. I keep eyes pointed in;

Hoping that, when the devil days of my hurt

Drag out to their last dregs and I resume

On such legs as are left me, in such heart

As I can manage, remember to go home,

My taste will not have turned insensitive

To honey and bread old purity could love.

Gwendolyn Brooks, “my dreams, my works, must wait till after hell” from Selected Poems. Copyright © 1963 by Gwendolyn Brooks.

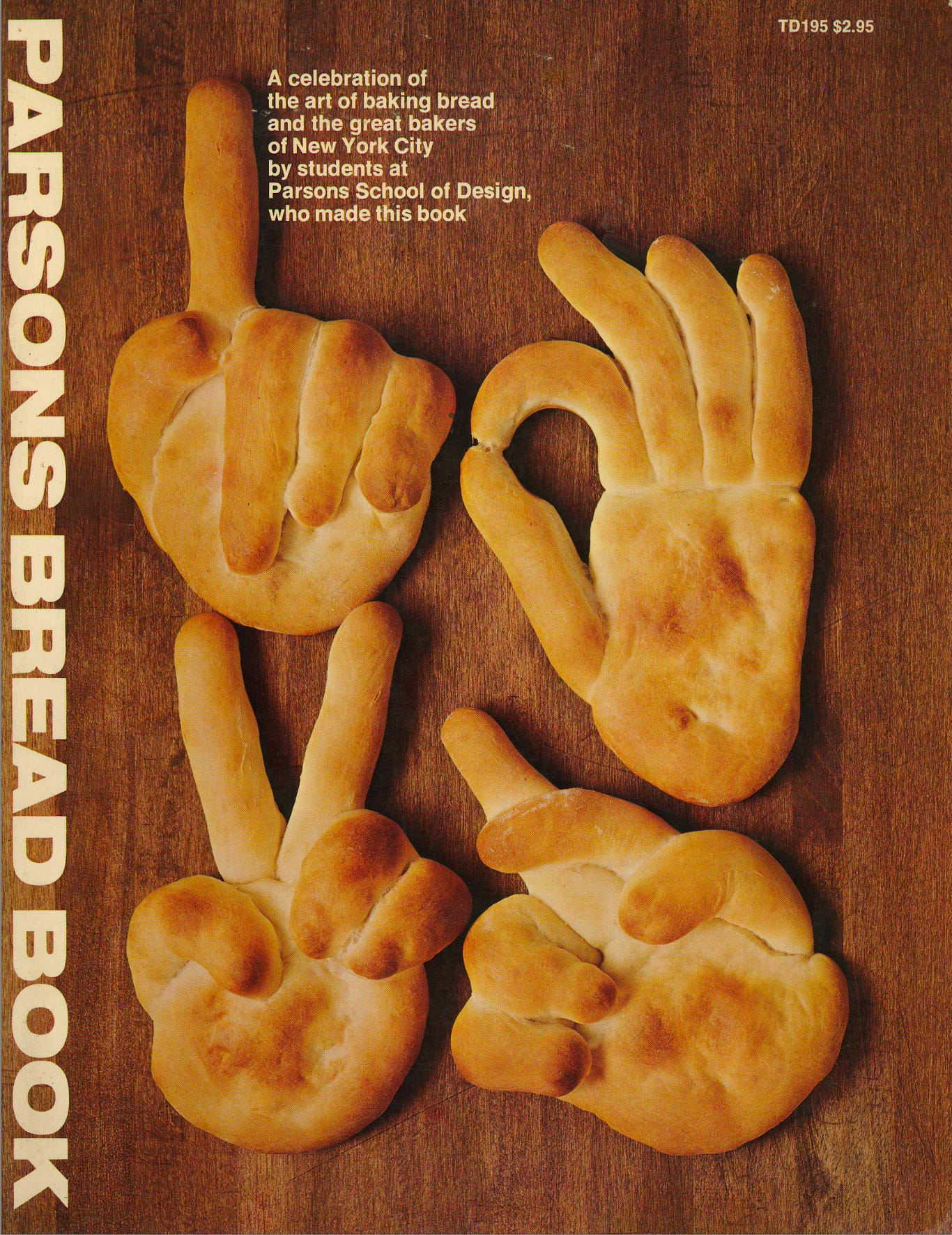

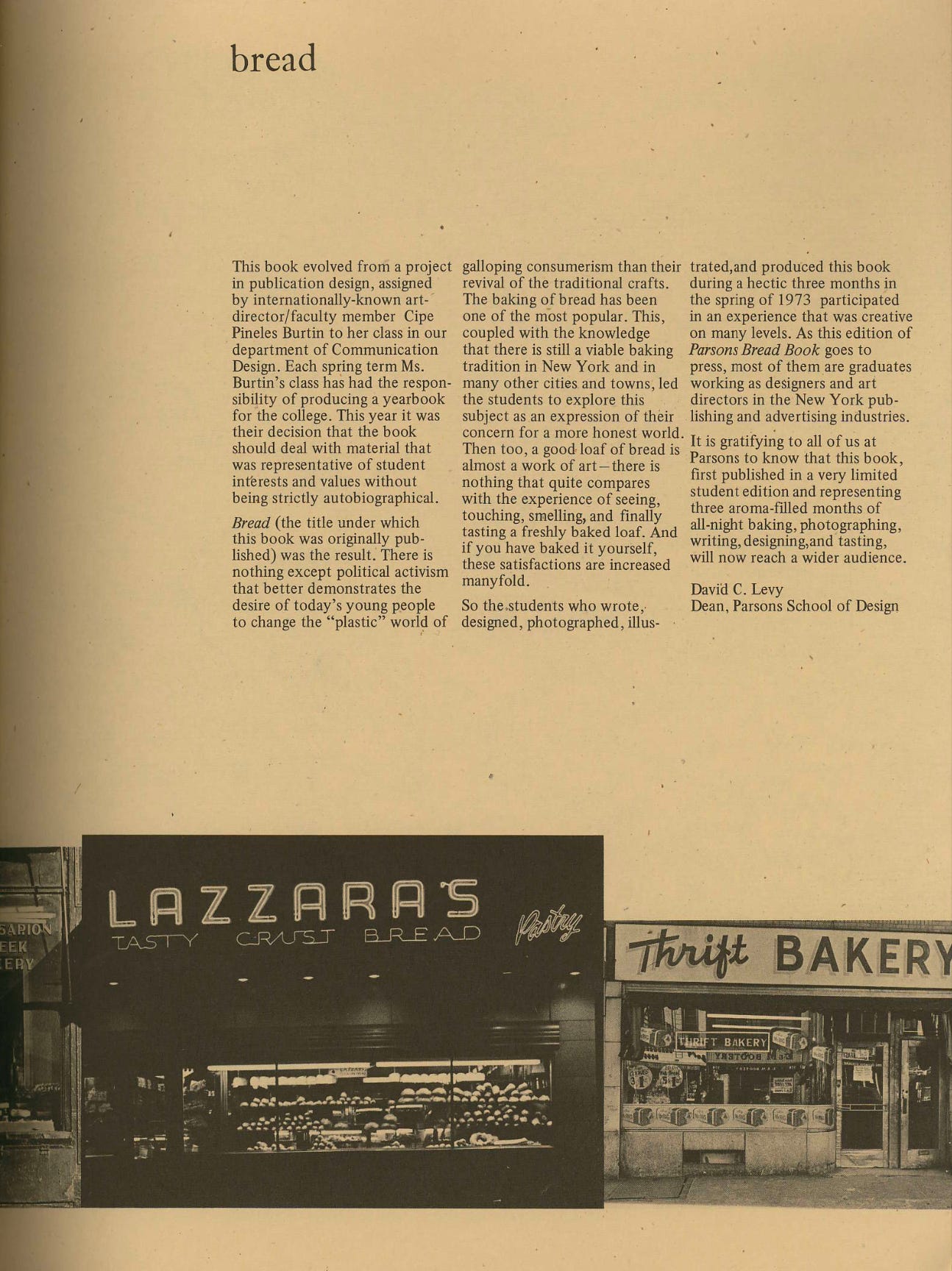

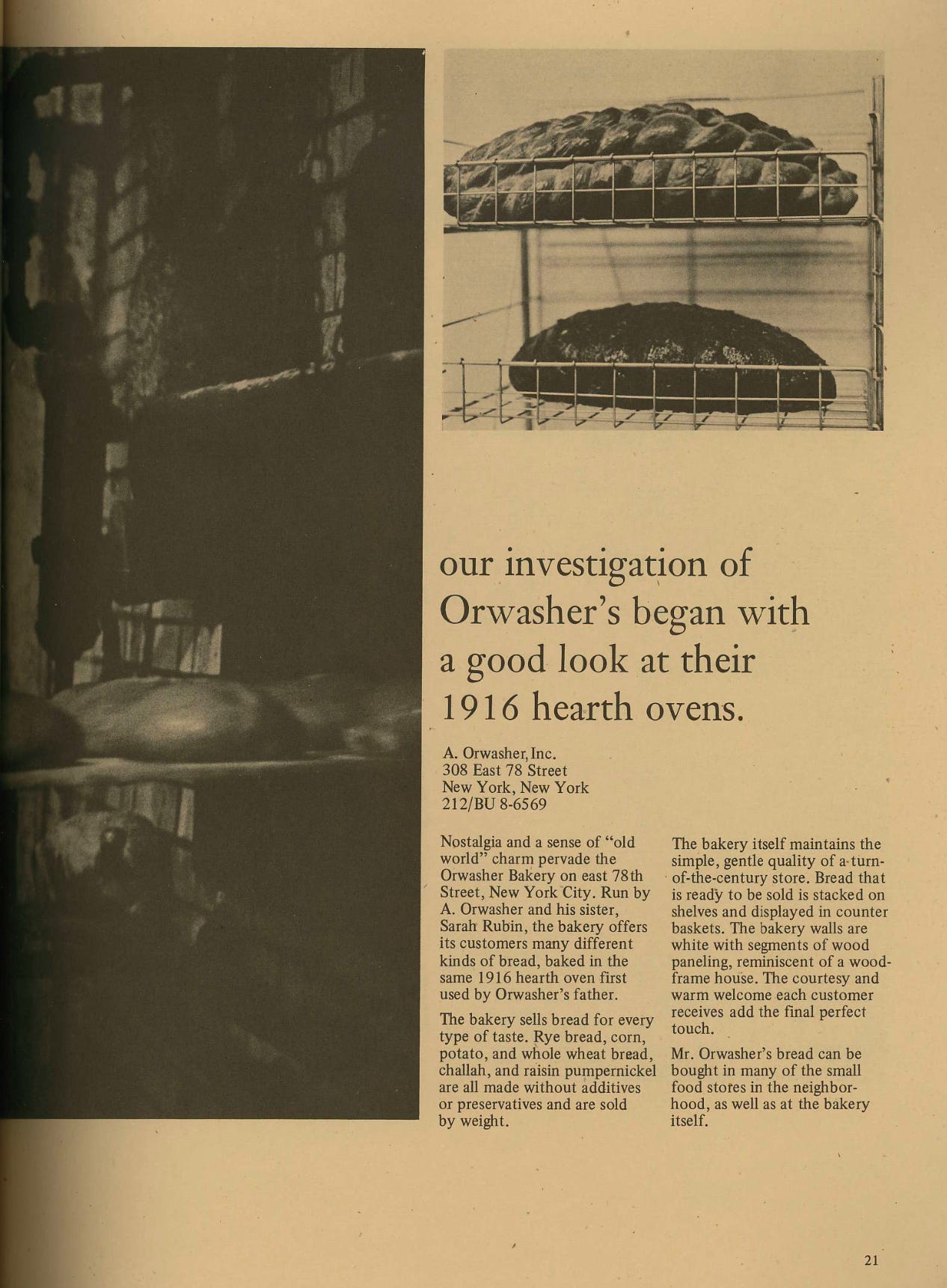

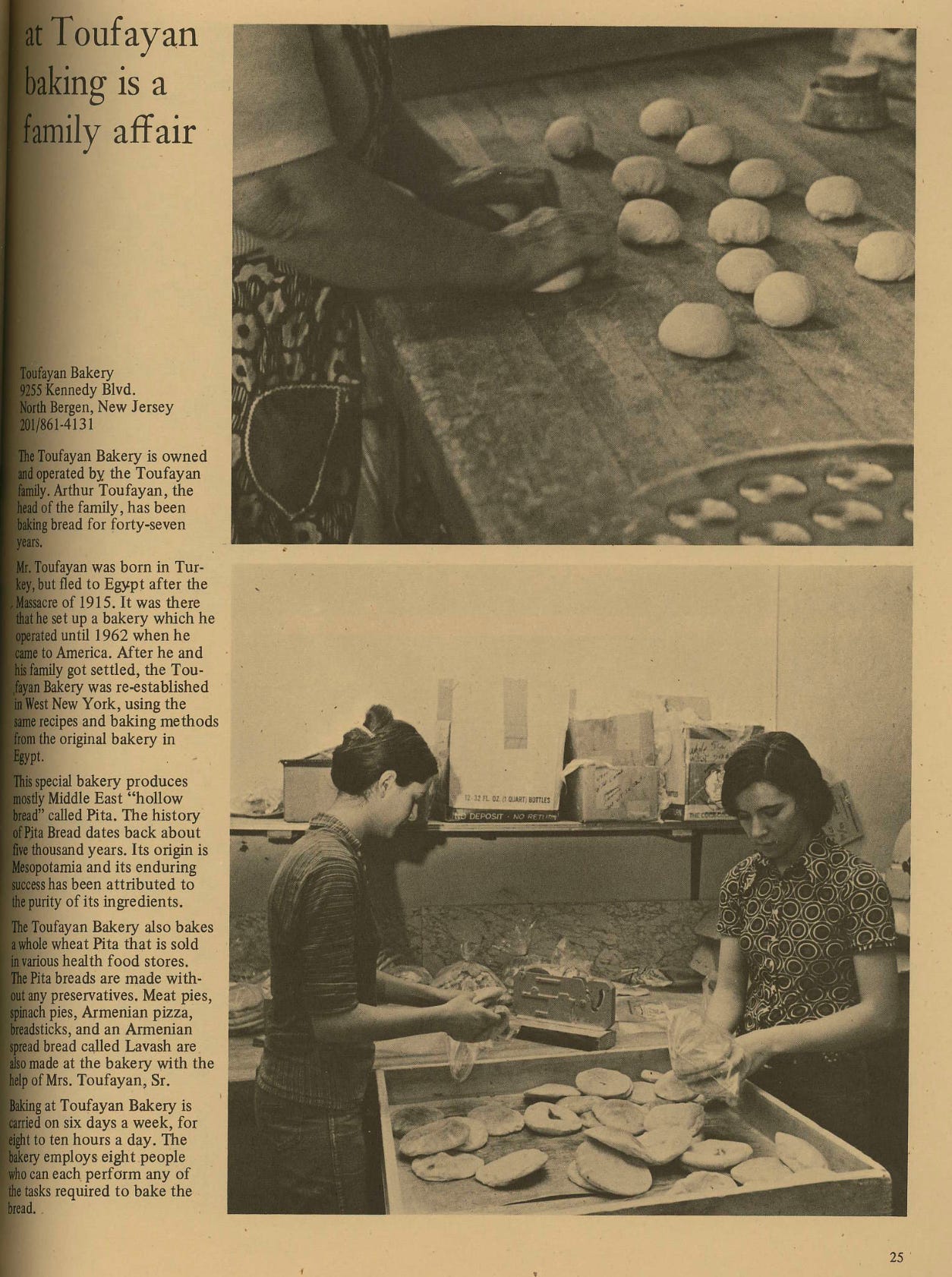

The plastic world of galloping consumerism

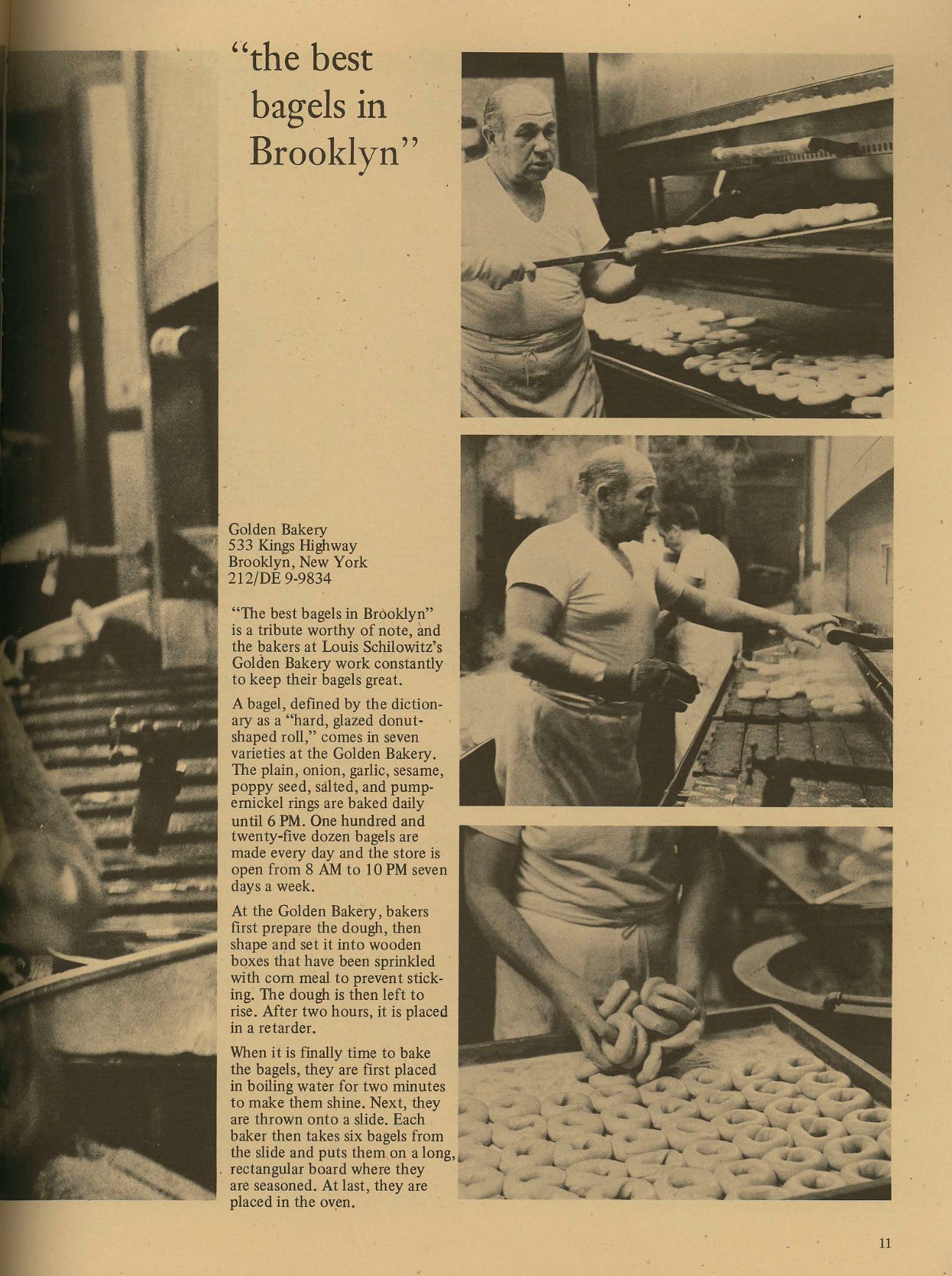

One of my favorite bread books is the Parsons Bread Book, created in 1974 by students in not-renowned-enough graphic designer and illustrator Cipe Pineles’s editorial class at the Parsons School of Design. It contains a series of profiles and photographic portraits of bakeries in and around New York City, many of which are no longer in operation.

The Parsons Bread Book is an amazing record of a bygone era in bread baking and of NYC history, and is sadly long out of print. Copies are available for sale online, but they are pricey. (I found my own years ago, before it was recognized as a rarity.) The good news is that the entire book is available to download as a PDF.

That’s it for this week’s bread basket. Have a peaceful weekend everyone, see you all next week.

—Andrew

Thank you for sharing the Parson’s Bread Book, Andrew! Wow!

That book is freakin' amazing. How cool and thank you for sharing it. I particularly appreciated the inclusion of the home bakers and the recipes were so interesting as well as the innovative shaping that so many did. This book literally illustrates the magic of bread, often on a grand scale (125 dozen bagels a day!!) with bakers working by hand. It's an art and a craft in a (mostly) bygone era but so important to remember/honor/emulate these ancestral teachers.