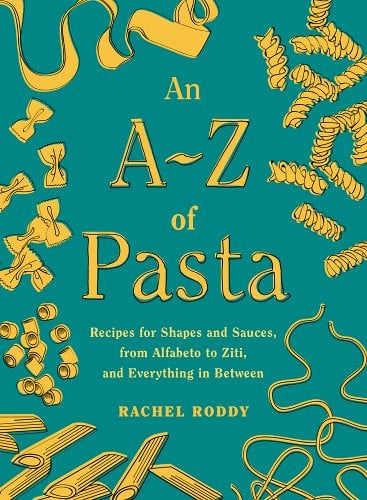

Continuing with Breadcrumb Month here at Wordloaf, we have an excerpt and a recipe from Rachel Roddy's new book An A-Z of Pasta, a book that I’ve had since it came out last year in the UK and love very much. Rachel is one of my go-to authorities on Italian food and pasta, and this book is an abecedarium of 50 essays on 50 pasta shapes, along with 100 recipes using them.

Rachel and her publisher generously allowed me to share an excerpt from one chapter from the book, on anelli, the hoop-shaped tiny pasta that is familiar to most Americans as one of the shapes used in Spaghettios and Chef Boyardee canned pastas. This is also the section of the book that serves as Rachel’s primer on the various types and classes of Italian pasta one might encounter.

The recipe is for Timballo di anelli siciliano, or a timbale of Anelli baked with tomato, eggplant and cheese (and breadcrumbs, of course), an elegant-if-not-hard-to-make showstopper pasta dish.

For Wordloaf paid subscribers, I’ve got a copy of An A-Z of Pasta to give away in a drawing. Just comment below with your favorite pasta dish — bonus points if it involves breadcrumbs; I’ll choose a winner at random in a week.

—Andrew

— a —

Anelli

A favorite bag to pull from the shelf, the little rings pressed up against the plastic like kids’ faces against a car window. I have a pasta-map tea towel. On it anelli float like tiny life-rings in the stretch of sea between Sicily and the heel of Puglia, the two regions in which they are most typical. For my Sicilian partner Vincenzo they are a shape of his childhood, one that holds personal and collective history. They are part of my childhood too, hooped-tinned memories. The pasta encyclopedia defines anelli as a factory-made, durum wheat and water dried pastina that comes in various sizes and goes by various names—anelli, anelletti, anellini, anelloni d’Africa. While anelli are typically served in broth, they are also well dressed with tomato sauce and fried eggplant, layered with cheese and baked for a timballo, which I will come to shortly.

A favorite bag to pull from the shelf, the little rings pressed up against the plastic like kids’ faces against a car window. I have a pasta-map tea towel. On it anelli float like tiny life-rings in the stretch of sea between Sicily and the heel of Puglia, the two regions in which they are most typical. For my Sicilian partner Vincenzo they are a shape of his childhood, one that holds personal and collective history. They are part of my childhood too, hooped-tinned memories.

Pasta shapes are edible hubs of information: flour and liquid microchips containing huge amounts of data, historical, geographical, political, cultural, personal, practical. Each shape can also be defined physically by its geometry, makeup, and category. And while this book isn’t a catalogue, certain terms will come up often so it seems a good idea to clarify a few things before we move on.

Fresh pasta or dried pasta. All pasta starts off fresh, and therefore soft, whether it’s a strand of spaghetti extruded in a factory, an ear of flour and water orecchiette, or a ribbon of egg tagliatelle you have made yourself. In referring to dried pasta I mean pasta shapes that have been made specifically—usually in a factory—to be dried so they last indefinitely. Fresh pasta, whether flour and egg, or flour and water, is made to be eaten while it is still fresh and soft.

Pasta, from the word impasto—a magma of flour and liquid—can be made from any flour; the Italian pasta lexicon includes shapes made from chestnut flour, acorn flour, rice flour, corn flour, fava bean flour and buckwheat. The hard king and tender queen, though, are hard or durum wheat semolina flourand soft wheat 00 flour. Simple, and really all we need to know as shoppers and eaters, although as cooks a bit more information is useful.

Hard or durum wheat, Triticum durum, grano duro, is the hardest variety of wheat. High in protein, durum’s hardness mustn’t be confused with what we consider “hard” wheat in English, that is, high-protein bread flour, but rather refers to the fact that it is stubborn and resistant to milling, eventually reducing to a granular texture the color of pale egg yolks. Ground coarsely, it becomes semolina suitable for puddings, or the basis for African and Levantine couscous. Ground twice it becomes flour, semola rimacinata in Italian, durum wheat semolina flour in English. Hard wheat flour absorbs water greedily, producing a dough with real substance, which is why it is ideal for making flour and water pasta. It is the legally stipulated flour for factory-made dried shapes in

Soft wheat flour, Triticum aestivum, grano tenero, is a separate species from hard wheat. Low in protein, its softness means it is a pushover, milling easily into powdery flour, its precise grade of milling noted in numbers, 00 being the finest, then 0, 1, 2 increasingly coarse. Soft wheat produces a more elastic dough, so is used to make fresh and fresh egg pasta. It is worth sticking your hands simultaneously into two bags, one of hard wheat semolina flour, the other soft wheat flour, to understand the difference. Hard wheat semolina flour is gently gritty and like very fine sand compared to the infinite smoothness of soft wheat 00 flour.

Factory-made and homemade. Leaky definitions, with many shapes being both, especially now that people have powerful domestic extruders producing shapes once exclusive to factories, and traditionally homemade shapes being made on an industrial scale. Overwhelmingly though, dried pasta is factory-made, while fresh shapes, both flour and water and flour and egg, are homemade or made on a smaller scale.

Extruded or cut or dragged. Extruded shapes are made by being forced through a die, which means many of the tubular and rounded flour and water dried shapes, also all the long ones with a rounded cross-section—spaghetti, linguine, bucatini, ziti. Cut shapes are made by cutting the dough, whether fresh or dried—tagliatelle, pappardelle, mafalde, lasagne. Dragged shapes are formed by a dragging motion.

Most useful, maybe, are the 6 categories of pasta shapes that take in all the above, fresh and dried, all flours, factory-made and homemade.

Pastine. Very small pasta shapes that are generally cooked in broth, therefore requiring a spoon. Pastine can be fresh or dried, and are made with hard or soft wheat, and other flours too. Most pastine, though, are dried factory-made hard wheat and water shapes.

Pasta corta, short pasta. Short shapes, both factory-made and homemade, so quills of penne and spirals of fusilli, also lozenge-shaped fregnacce.

Pasta lunga, long pasta. Long shapes, both factory-made and homemade, including spaghetti, obviously, tagliatelle, fettuccine, pappardelle; also flour and water pici and lagane.

Pasta ripiena, filled pasta. Stuffed or filled shapes, so ravioli and tortellini, also rolls of cannelloni and all the layered, baked pastas.

Strascinati, dragged shapes. Shapes made by being dragged across a surface with either a finger or an implement. Orecchiette, the ear-like pasta from Puglia, is probably the most famous of these, but there are many others.

Gnocchi. Shapes with a dumpling form, which may or may not be ridged or indented.

Some shapes straddle two categories. Gnocchi ricci, for example, are gnocchi but also dragged, while maccheroni, fusilli and lasagne can mean many things. Also bear in mind that many shapes have many names, and that while classifying pasta is helpful it is not an exact science and at times is as slippery as a just-cooked ribbon of fettuccine.

So back to the second shape of this alphabet, anelli, pressing up against the side of the bag like eager faces. As I mentioned, they can be served in broth, which you can then cloud with cheese, or brothy soup. Or they can be parboiled, dressed with sauce, pressed into a tin, and baked into a timballo that you invert with a triumphant ta-dah.

Timballo di anelli siciliano / Anelli baked with tomato, eggplant and cheese

Serves 6

Timballo is also a name for a drum. In Sicily this timballo is traditionally made on the 15th of August, Ferragosto, the workers’ holiday that dates back to Emperor Augustus’s Feriae Augusti, and to the Assumption of the Virgin. Often, it is taken to the beach along with a whole watermelon that is buried in the sand near the water to keep cool. By Sicilian standards this is a modest timballo. It can be embellished, the tomato replaced with meat ragù, bolstered with tiny meatballs or crumbled sausage, and you could add peas or the Sicilian favorite—slices of hard-boiled egg. However you make it, season generously at every stage. You can make individual servings, known as sformati for their easygoing form, the benefit of which is a high proportion of edges and crust.

1 onion, peeled and small diced

salt and black pepper

½ cup olive oil

1 (14.5 oz/411g) can whole peeled tomatoes

1 lb (500g) tomatoes a pinch of red pepper flakes

a handful of fresh basil

1 large eggplant (plus oil for frying)

14 oz (400g) anelli, alternatively ditalini, tubetti, mezze penne

4¼ oz (120g) Parmesan or caciocavallo, grated

butter

fine breadcrumbs

14 oz (400g) mozzarella or scamorza, diced or ripped into little pieces

You will need an 11-inch round baking pan 4 inches deep—ideally with a removable bottom—or a bundt pan. Or 6 small dishes, or—as is typical in Sicilian rosticcerie— aluminum trays.

First make the sauce. In a large heavy-bottomed pan, fry the onion and a pinch of salt in the olive oil over medium-low heat until soft and translucent.

Use scissors to chop the canned tomatoes. Peel the fresh ones by plunging them into boiling water for 60 seconds, then into cold water, at which point the skins should split and slip away easily. Chop the tomatoes roughly, separating away most of the seeds, then add to the pan, along with a good pinch of salt, pepper flakes, and a sprig of basil. Bring to a boil, then reduce to a simmer and cook for 30 minutes. Allow to cool a little.

Cut the eggplant into ½-inch cubes. Either rub with oil and bake in the oven (set to 400°F), or deep-fry in a few inches of hot oil, then drain on paper towels and sprinkle with salt.

Bring a large pot of water to a boil, add salt, stir, then add the anelli and cook until al dente. Drain.

Mix the pasta with the sauce, eggplant, half the Parmesan and a few grinds of black pepper.

Butter the baking pan, then dust carefully with breadcrumbs. Half fill the pan with pasta and sauce, then make a layer of mozzarella or scamorza, pressing them into the pasta. Arrange a few leaves of basil on top and sprinkle with the remaining Parmesan, then cover with the rest of the pasta and press down firmly.

Dust the surface with more crumbs and dot with butter. Bake at 350°F in the middle of the oven for 30 minutes for a single timballo or 12 minutes for smaller ones, or until the crumbs are golden and the top is bubbling. Wait 10 minutes before inverting the large timballo onto a serving plate.

From An A-Z of Pasta: Recipes for Shapes and Sauces, from Alfabeto to Ziti, and Everything in Between: A Cookbook © 2023 by Rachel Roddy. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

First of all I love Racheal and Timballo. Actually I had my first Timballo with her in Sicily at Anna Tasca Lanza. My favorite pasta is hands down tomato sauce with hand shaped Sicilian maccaruni. This worm like long "macaroni" like pasta is made with water and double milled semolina (semola di grano duro rimacinata). Traditionally you shape the maccaruni with a straw but I find its better to use thin metal rods from the art supply shop. And yes I don't mind topping the tomato sauce with butter toasted bread crumbs ;)

Sounds delish. Last night I made one of my new favorites - butternut squash gnocchi with a basil cream sauce. But my all-time fave is... Spaghetti Os. I'm not kidding!